Introduction

To effectively immobilise the HIV capsid protein with our DNA structures, we need to ensure that we can bind protein to DNA. The binding of protein to other biomolecules (bioconjugation) is key step for many endeavours, such as in diagnostics, biomolecular imaging and most pertinently to this investigation, in the measurement of biological interactions.1 As such, there are numerous established methods of bioconjugation, and the selection of an appropriate method depends on protein origin, purity, specificity requirements and other application based requirements.2 Figure 1 illustrates the general concept of bioconjugation as applied to this project.

Figure 1: Preparation of a bioconjugate - a deceptively complex process with different solutions for different needs.

Conjugation Techniques

High yield bioconjugation has been achieved with bulk modification of lysine residues with an N-hydroxysuccinimide (NHS) compound.3 However, this high yield is mainly owing to the commonality of surface lysine residues on most proteins, and so this technique involves a tradeoff with conjugation site specificity. More selective forms of modification have exploited the chemistry of naturally occurring amino acids. Such techniques include targeting tryptophan residues with metallocarbenoid reagents,4 reacting tyrosines with diazonium salts,5 and altering cysteine groups with maleimide6 or iodoacetamide compounds.7 In general, these selective methods are more successful with recombinantly expressed proteins rather than those extracted from their native environments as these can be modified with site specific mutations.2

However, even with the tool of selective or site-directed mutagenesis it is challenging to create a specific conjugation site by exploiting the chemistry of natural amino acids. This is because proteins typically contain multiple instances of the target residue and/or the residue in question is functionally important. A more recent bioconjugation technique uses a highly specific coupling between a short peptide designated SpyTag and a corresponding protein partner Spy Catcher, each being one of the two domains of the FbaB protein from Streptococcus pyogenes.8 The pair form an irreversible isopeptide bond upon meeting as they reassemble into the complete protein. Expressed proteins have also been conjugated via the appendage of a polyhistidine (His6) tag, which can interact with polar functional groups such as nitrilotriacetic acid (NTA) through shared complexation of metal ions.9 This form of chemistry is already widely used in protein purification,10 and is distinct from other conjugation methods in that the underlying reaction is reversible.

Selection of Methods

The bioconjugation methods to be used in this project were chosen while trying to encompass a wide range of bond strengths and specificities. Three main types of conjugation chemistry have been explored, and these will be explained in turn:

- Nitrilotriacetic Acid (NTA) / Nickel (Ni) / His6 Coordination Chemistry

- Succinimidyl 4-(N-maleimidomethyl)cyclohexane-1-carboxylate (SMCC) / Cysteine (Cys) Covalent Chemistry

- Spy Catcher/Spy Tag Isopeptide Bond

The first method is a form of reversible chemistry involving the coordination of metal ions. This means that the bonds formed are relatively weak and can be undone under appropriate conditions. The second is based on targeting cysteine with a reactive maleimide group, which forms covalent bonds but is sometimes limited in specificity. The final method uses a peptide/protein partnership, the species involved form a covalent isopeptide bond upon meeting which is extremely strong and highly selective.

Aims

This area of the project aims to ensure practical and consistent production of the materials necessary to allow conjugation of HIV capsid protein to DNA structures using the techniques outlined above. Proteins are equipped with the required functional groups through specific mutations during the expression process. This aim of this area then becomes to produce sufficient DNA oligonucleotides modified with the functional groups able to achieve bioconjugation by interacting with those already present on protein constructs.

A secondary aim for this section is to improve production throughput by identifying and removing bottlenecks in the methods used to develop conjugation materials. This will contribute to the main aim of achieving practical levels of bioconjugation material production.

Results/Discussion

Method 1 - NTA/Ni2+/HIS6 Coordination Chemistry

The materials required for this technique are DNA modified with nitrilotriacetic acid groups, protein fitted with a His6 tag, and a solution of nickel ions. Both the NTA groups (on the DNA) and histidine tags (on proteins) can form complexes with metal ions, particularly the Ni2+ ion. Combining these three elements leads to the joint complexing of nickel by both protein and DNA, creating a DNA-protein bond which is mediated by nickel ions. Insertion of a His6 tag was achieved by introducing a mutation during protein expression, meaning that this project was focussed on the modification of DNA with NTA groups and subsequent purification.

NTA Modification of DNA

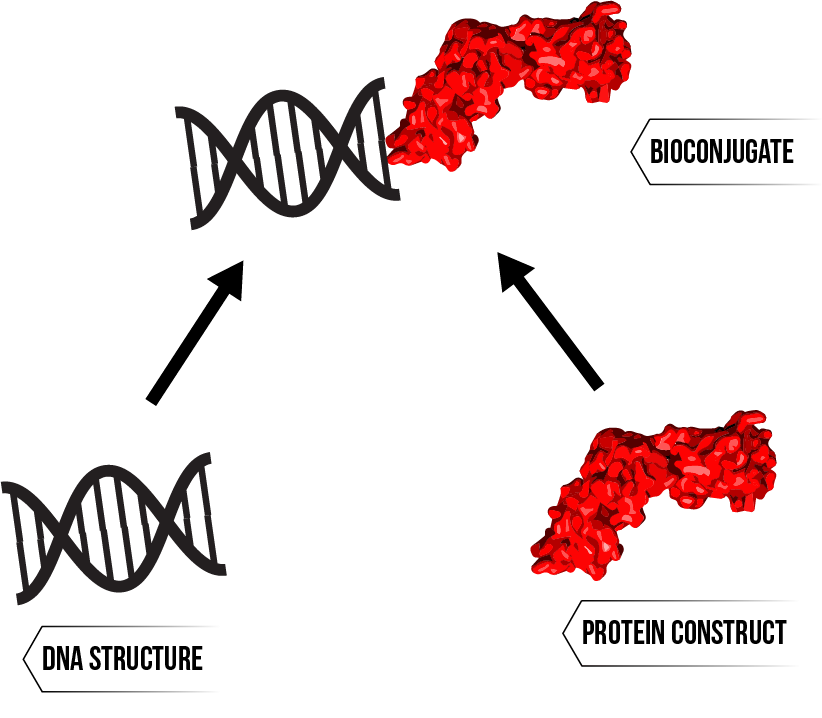

The first step of DNA modification is the attachment of the crosslinking molecule N-succinimidyl 3-(2-pyridyldithio)propionate (SPDP) to short DNA oligonucleotides functionalised with three amine groups. Next, the disulphide bond of the SPDP is reduced using tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine (TCEP) to remove the pyridine moiety, yielding DNA with a single accessible thiol group. The final step is to react the thiolated DNA with maleimide NTA, which completes the attachment of the NTA group to the DNA backbone. The successful attachment of NTA groups causes an increase in size of the target DNA, which can be observed with denaturing polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) to confirm the success of the reaction. Figure 2 summarises the modification procedure and gives a typical denaturing PAGE result where the mobility of the DNA has been reduced post modification, reflecting the change in size due to NTA modification.

Figure 2: Schematic of NTA modification process. Inset – urea denaturing PAGE visualisation of procedure, samples correspond to the first three stages in the schematic. Click here for full description of gel conditions and modification procedure.

Notably, there are three distinct bands which form upon addition of maleimide NTA, suggesting that tris NTA DNA is not the only product of this reaction. This is attributed to the fact that the modification does not go to completion, and the products of the reaction are divided between tris, bis and mono modified NTA DNA.9 This presents the need to purify the reaction mixture.

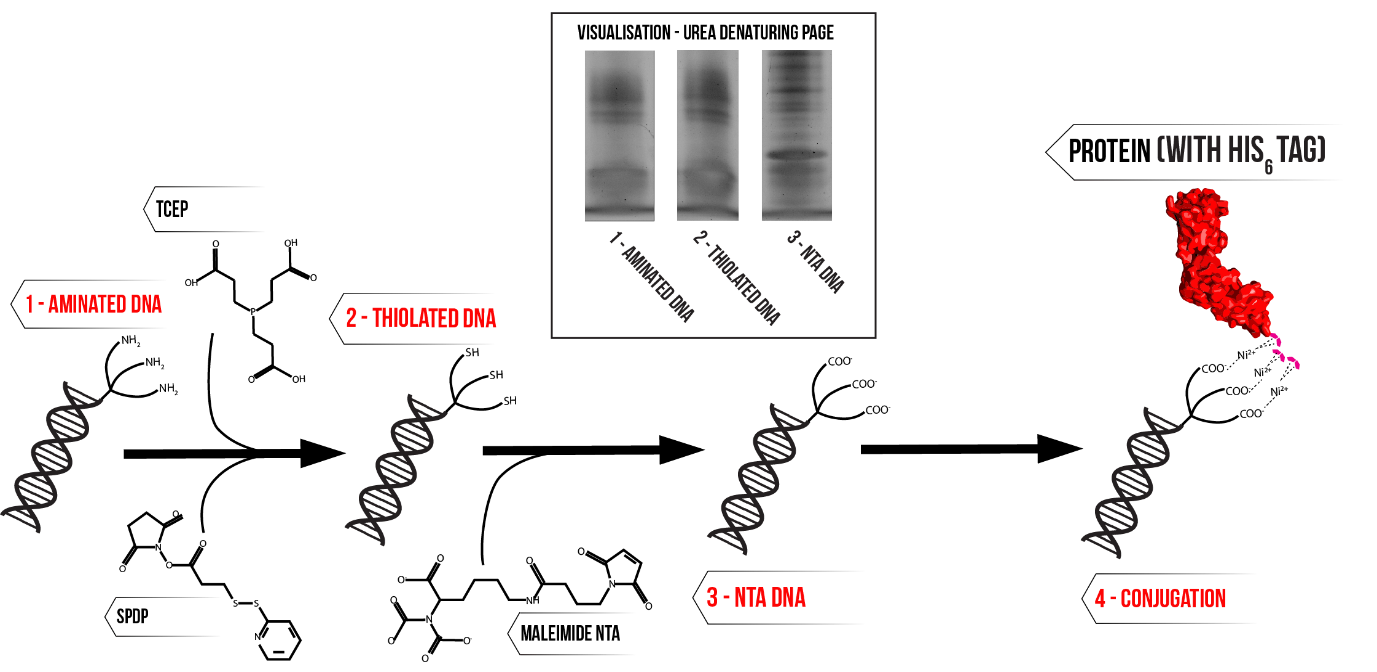

Purification of NTA Modified DNA

Purification aims to separate the tris NTA DNA from the reaction mixture, as this should provide the most favourable binding with protein. An effective purification also ensures consistency of the modified DNA, which is an important consideration for other areas of the project. The similarity of tris, bis and mono NTA DNA on the molecular level makes this a difficult separation, however there are slight differences in size and charge which can be exploited using PAGE. Figure 3 displays the relative positioning of the variously modified DNA during a typical PAGE purification. It was also noticed that the purification could still be performed using polyacrylamide gels that had been cast without a well comb. The results of this modified procedure are also given by Figure 3, demonstrating that the throughput of the purification was more than doubled without any visible loss in resolution.

Figure 3: Purification of tris NTA DNA from its bis and mono counterparts. Click here for a full description of the purification method.

The tris NTA band, highest on gels depicted in Figure 3, was excised and subject to a multi-stage extraction process involving leaching, centrifugation and buffer exchange. The resulting purified Tris NTA DNA was stored at -20°C and used as required to immobilise His tagged protein constructs through their shared affinity for nickel cations.

Method 2 - SMCC/Cys Covalent Chemistry

This method of conjugation differs from NTA based chemistry in that it is irreversible. The process involves modifying mono-aminated DNA with the heterobifunctional crosslinker SMCC,11 which is known to form covalent bonds with thiol groups. A cysteine residue is introduced into the target protein by selective mutation, allowing the protein to be directly conjugated to the modified DNA.

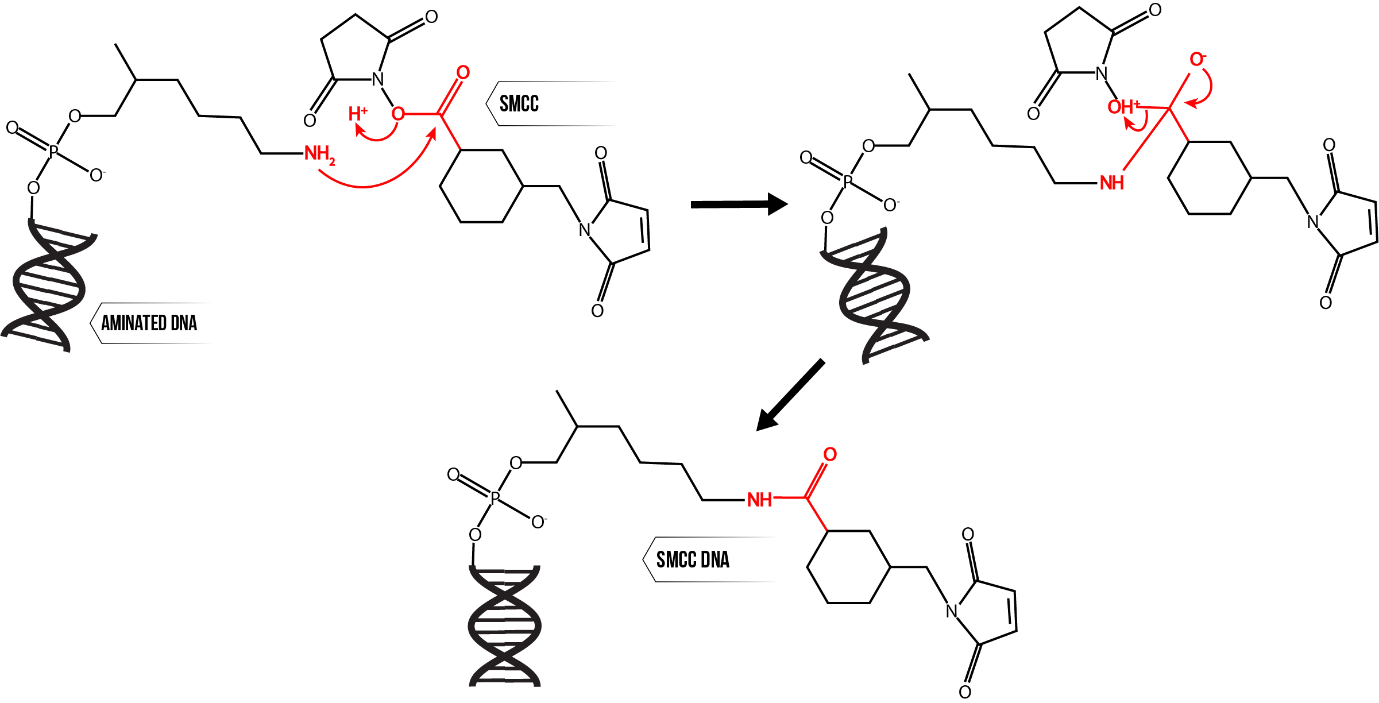

SMCC Modification of DNA

A mechanistic depiction of SMCC modification of DNA is shown in Figure 4. Aminated DNA is added to a mixture of dimethyl fluoride (DMF), N,N-Diisopropylethylamine (DIPEA) and SMCC. DMF is the reaction solvent, and DIPEA is a strong non-nucleophilic base which catalyses the reaction between aminated DNA and SMCC. The proposed mechanism for this reaction (Figure 4) is via nucleophilic substitution, which is in general practically irreversible. In addition, SMCC is added in large excess meaning there is negligible unmodified DNA remaining at the end of the reaction.11

Figure 4: SMCC modification of aminated DNA, proceeding through nucleophilic substitution.

Purification of SMCC DNA

The main contaminant in this mixture is unreacted SMCC, which must be removed to provide effective modified DNA for conjugation purposes. This separation was successfully achieved with two consecutive methods, ethanol precipitation and desalting.

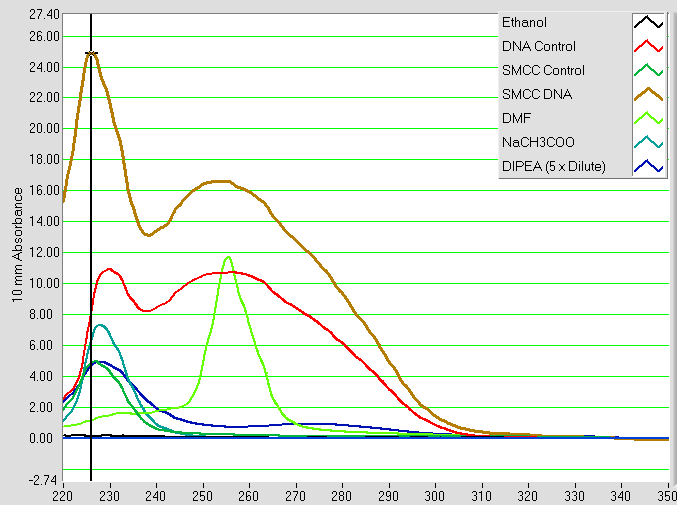

Ethanol Precipitation

This step exploits the fact that SMCC is soluble in ethanol, while DNA is not. The reaction mixture is adjusted to pH 5 with sodium acetate (NaCH3COO) and a large excess of ethanol added. It is then chilled to -80°C, encouraging the modified DNA to fall out of solution. The resulting suspension is centrifuged, and the liquid phase removed. This leaves behind a solid pellet of DNA, which is resuspended in water. The resulting solution of modified DNA is then characterised with UV-Vis Spectroscopy alongside appropriate controls, a typical result given by Figure 5.

Figure 5: UV-Vis absorbance spectra of SMCC modified DNA solution (‘SMCC DNA’) and controls. The ‘DNA Control’ is from an identical procedure using DNA with no SMCC added, and the ‘SMCC Control’ is vice versa. All other spectra belong to the various reagents involved as shown by the legend.

Two distinct peaks are observed, one at 228 nm and the other at 255 nm. The former peak is present in all three of the SMCC DNA reaction mixture, the SMCC control and the DNA control. This implies that it is caused by substances common to all three of these samples. Based on the spectra of the individual components, the most likely cause is the presence of some combination of residual DIPEA and residual NaCH3COO following the precipitation. The latter peak is believed to represent DNA, as this is absent from the SMCC control but present in both the SMCC DNA reaction mixture and DNA control. There is the possibility of some interference from residual DMF, which can also be seen to absorb light at 255 nm, however as a volatile small molecule most of this is likely to be removed either during evaporation in this stage or size exclusion in the following stage of purification.

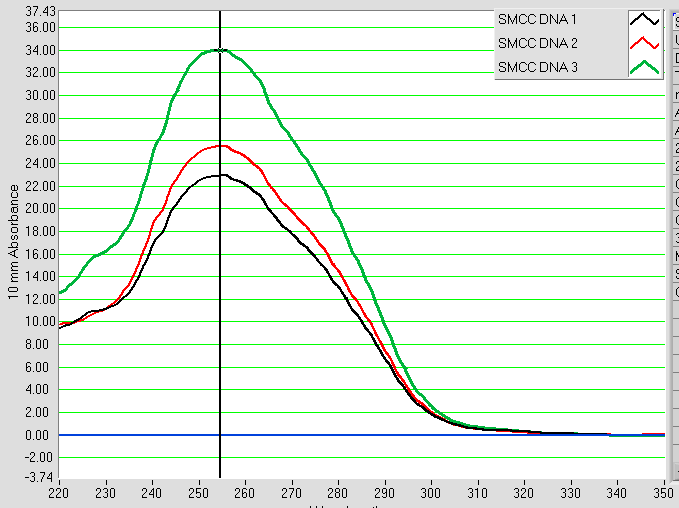

Desalting

The mixture is spun through a column packed with water-equilibrated porous G10 resin, which selects for the modified DNA by size exclusion. The effective removal of residual contaminants is shown by Figure 6 with the disappearance of the UV-Vis absorbance peak at 228 nm, leaving only modified DNA at 255 nm.

Figure 6: UV-Vis spectra of SMCC modified DNA solutions after both ethanol precipitation and desalting (run in triplicate).

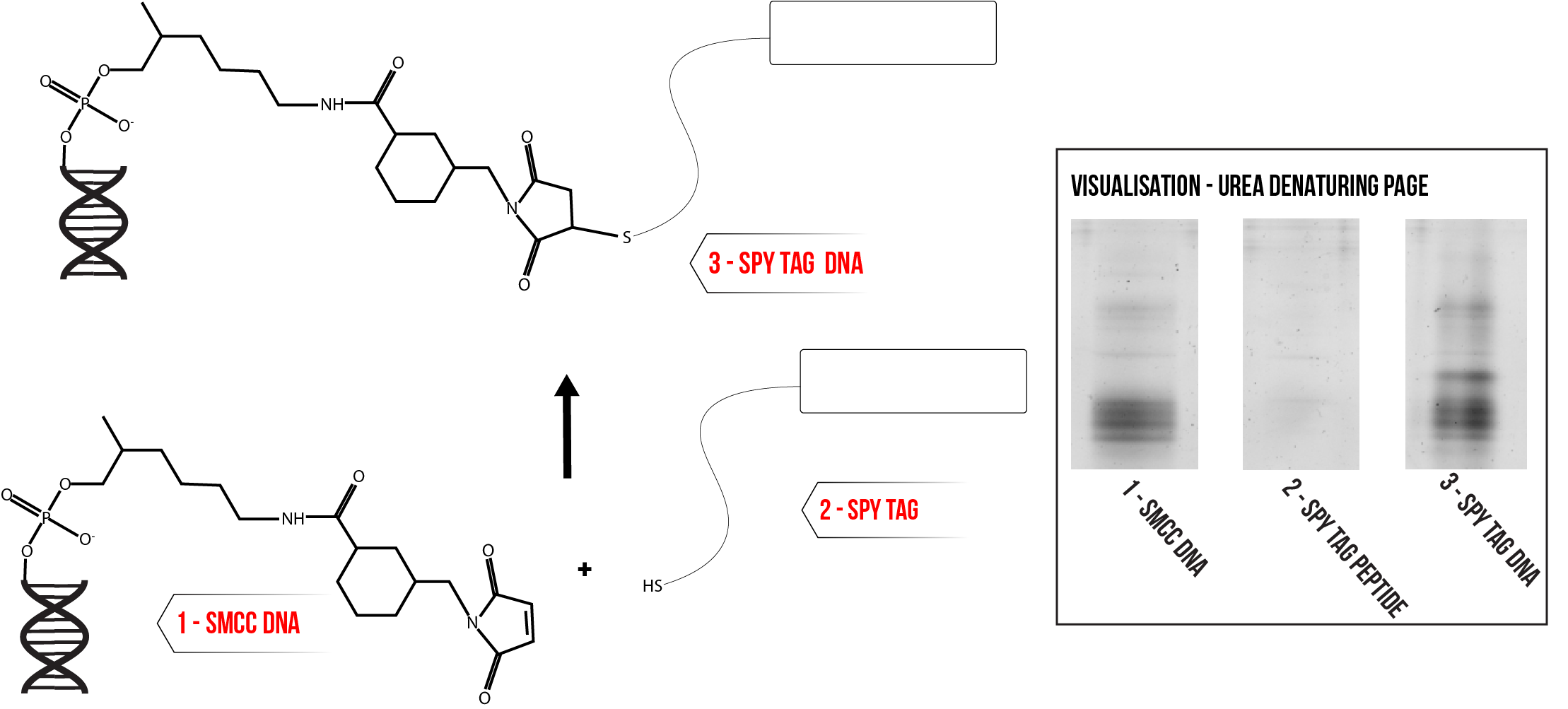

Method 3 - SpyCatcher/SpyTag Isopeptide Bond

Unlike most peptide/protein interactions, this technique involves a highly selective and irreversible chemical reaction centering on the formation of an isopeptide bond between the short peptide SpyTag and its protein partner SpyCatcher. In this project, SpyCatcher has been appended to protein constructs as a mutation during expression, while SpyTag is conjugated to DNA. The opposite configuration is possible, but was not explored in this project.

Conjugation of SpyTag to DNA

SpyTag is a short peptide with a cysteine residue, meaning that it can be conjugated to SMCC modified DNA. The peptide is first incubated with a molar excess of TCEP to reduce any disulfide bonds between peptides. The reduced peptide is then added in large molar excess to SMCC modified DNA, the mixture buffered to pH 7.5 and reaction allowed to proceed for two hours. The successful addition of the peptide increases the size of the SMCC modified DNA, leading to a band shift which can be visualised using PAGE analysis as shown by Figure 7. Comparison with the SMCC DNA control suggests that the reaction yield is relatively low and there is still a substantial amount of unconjugated DNA at completion.

Figure 7: Conjugation of SpyTag to SMCC Modified DNA. Inset – urea denaturing PAGE analysis of conjugation reaction mixture alongside appropriate controls. Click here for full description of gel conditions.

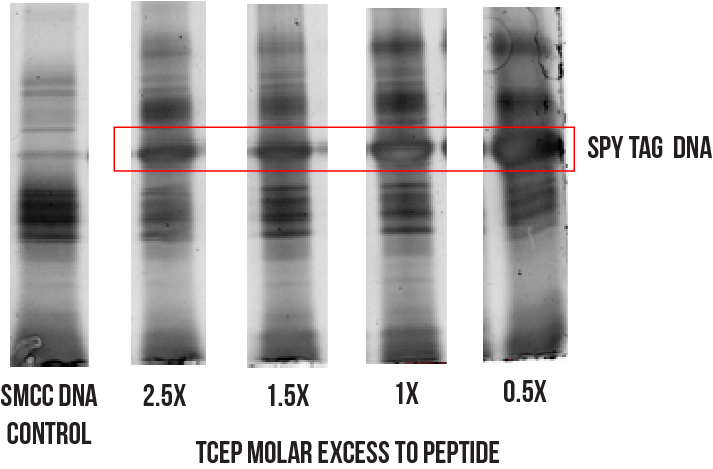

One possible cause of the low yield is an undesirable side reaction between TCEP and the maleimide group on the SMCC modified DNA.12 To investigate this premise, the conjugation was conducted while varying the excess of TCEP used during peptide reduction. The different reaction mixtures were visualised using PAGE, and the prominence of the bands corresponding to the Spy Tag DNA conjugate compared. Figure 8 summarises the results of this screening process, with a considerable improvement in yield observed as shown by the growing prominence of the conjugate band with decreasing molar excess of TCEP.

Figure 8: Effects of lowering molar excess of TCEP on conjugation reaction.

Despite an improved yield, it seems that there is still a small amount of unconjugated DNA remaining at completion. A much more prominent contaminant, though not visible on the gel in Figure 8, will be the substantial amounts of unconjugated peptide remaining from the 10 x molar excess addition of peptide to SMCC DNA. Hence, further separation is needed to obtain purified SpyTag DNA.

Purification of SpyTag DNA

An attempt was made to separate the various components in the conjugation reaction mixture by exploiting their relative solubilities in particular solvents. Several parallel conjugation reactions were initiated and allowed to proceed to completion. Each reaction mixture was then added to an excess of one of eight different solvents in the hope that this would cause selective precipitation of the desired species, thus enabling purification. Table 1 outlines the solvents used and provides a rationale for their selection.

|

Reaction ID |

Solvent Added |

Rationale |

|

1 |

800 µL Acetone |

Used to precipitate peptides14 |

|

2 |

800 µL Acetone + 50 µL pH 5 NaCH3COO Buffer |

|

|

3 |

800 µL Ethanol |

Used to precipitate SMCC modified DNA (above) |

|

4 |

800 µL Ethanol + 50 µL pH 5 NaCH3COO Buffer |

|

|

5 |

0.1 M TEAA + 5% Acetonitrile |

Previously used in attempts to purify mixture with HPLC, but this was thought to fail due to precipitation of certain species. |

|

6 |

0.1 M TEAA + 70% Acetonitrile |

|

|

7 |

0.1% TFA |

|

|

8 |

0.1% TFA + 90% Acetonitrile |

Table 1: Solvents used to encourage precipitation of various species in conjugation reaction mixture.

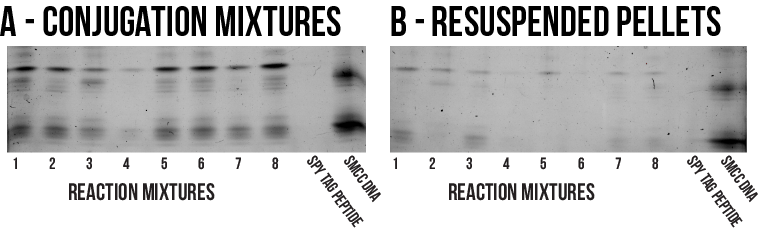

The mixtures were chilled at -80°C for 30 minutes and then centrifuged at 4°C for 30 minutes to encourage precipitation. The solid pellets resulting from each precipitation were then resuspended in deionised water. These were then analysed with PAGE alongside a sample from the initial reaction mixture normalised to the same concentration as the resuspended pellet, as shown by Figure 9.

Some precipitation has certainly occurred, though it seems most of the species involved remained solubilised during the process as the resuspended pellet bands are markedly less prominent than those of the corresponding reaction mixtures. As a result, it cannot be concluded that precipitation with any of the solvents surveyed represents a practical method of purification. In the absence of an effective separation, it is still possible to use the unpurified reaction mixture to conjugate proteins to DNA structures. However, the vast excess of unconjugated Spy Tag peptide will consume large amounts of Spy Catcher protein which is highly non-ideal. Therefore, further work is needed to establish a more efficient purification for this conjugate.

Conclusions

Three different forms of protein bioconjugation were selected from literature for the immobilisation of our various protein constructs onto DNA structures. Feasible and reliable chemical reactions were developed for the modification of DNA oligonucleotides with NTA, SMCC and SpyTag peptide.

Effective purification techniques were developed for the former two products, however further work is needed to develop a more effective purification for the SpyTag DNA conjugate.

Materials & Methods

Reaction Conditions

Unless explicitly mentioned, all reactions proceeded at 25°C in a temperature controlled laboratory.

Urea Denaturing Page Gels

All denaturing PAGE gels were prepared with casting moulds and associated equipment supplied by BioRad. Gels were cast in two layers, with 32% 19:1 acrylamide/bis-acrylamide in the lower (resolving) layer and 5% 29:1 acrylamide/bis-acrylamide in the upper (stacking) layer. Both layers contained 42 w/v% urea. Loading buffer used was added to samples at a 1:1 ratio immediately before loading and contained 27 w/v% urea, dissolved in a mixture of 60 v/v% 1M Tris HCl (pH 6.8) and 40 v/v% of a 1% bromophenol blue solution. Gels were run in 1 x Tris/Borate/EDTA running buffer at 150 V for 10 minutes followed by 250 V for 90 minutes.

NTA Modification

Tris-aminated DNA (Integrated DNA Technologies) was resuspended in nuclease free water to 1mM and stored in aliquots at -20°C. Immediately prior to reaction, this was buffer exchanged into a buffer solution with 100 mM Na3PO4, 100mM NaCl and pH 7.3 using pre-equilibrated SEC columns (Bio-Rad Micro Bio Spin 6). SPDP was added to 12.5 mM, left to react for one hour, and then excess removed with 2 more consecutive SEC columns. TCEP was added to 10 mM and incubated for 15 minutes, before adding maleimide-NTA to 20mM and allowing the reaction to proceed for one hour. Excess maleimide NTA was removed with another SEC column, and the products visualised alongside on a denaturing polyacrylamide gel with a SYBR-Gold post-stain.

Tris NTA DNA Purification

The reaction mixture was purified using PAGE. Eight 22% denaturing gels were cast as per standard procedure and the well combs deliberately not used when pouring the stacking gel. 20 µL of the NTA reaction mixture was diluted to 400 µL with deionised water and added to 400 µL of loading dye. This mixture was divided into 100µL portions, each of which was loaded on to one of the denaturing gels. After running, the gels were stained with SYBR-Gold and visualised on a blue/UV light box to determine the location of the tris NTA band. This band was excised, crushed and left sitting in 20mM Tris HCl (pH 8) overnight. The next day, the gel slurry was separated with centrifuge membrane filters (Spin-X) and the filtrate concentrated by vacuum evaporation. This concentrate was desalted using pre-swollen G10 resin and the final concentration determined by visualisation alongside known standards on a denaturing polyacrylamide gel with a SYBR-Gold post-stain to allow quantification.

SMCC Modification and Purification

2 mg of SMCC, 60 µL of DMF, 1 µL of DIPEA and 2 µL of aminated DNA at 10 mM were added to a clean Eppendorf tube and agitated for 30 minutes at room temperature. Following this, the mixture was diluted to 200 µL with deionised water, and added to 50 µL of pH 5 NaCH3COO buffer with 800 µL of absolute ethanol. This substance was chilled at -80°C for 30 minutes, then centrifuged at 14,000 g at 4°C in a pre-cooled centrifuge leading to the formation of a visible DNA pellet. The supernatant was removed, and the pellet dried in a 37°C incubator for 15 minutes before being resuspended with deionised water. This solution was then desalted using pre-swollen G10 resin, before being characterised with UV-Vis spectroscopy to determine yield and purity. The process was sometimes repeated if the UV-Vis spectra indicated the presence of contaminants. Once purified, the SMCC DNA was distributed into 1 nmol aliquots, vacuum evaporated until dry and stored at -20°C.

Spy Tag Conjugation

10 µL of Spy Tag peptide solution at 1 mM was vacuum evaporated until dry in a clean Eppendorf tube. This was added to 2 µL of deionised water, 1.5 µL of 0.5M NaCl, 1 µL of 0.1M Tris HCl (pH 7.5) and 0.5 µL of 10 mM TCEP. After incubating for 15 minutes, this was transferred to another tube containing 1 nmol of dried SMCC modified DNA and left overnight. The reaction was visualised on a denaturing PAGE gel with a SYBR Gold post stain.

Spy Tag DNA Purification

Following the addition of solvent, the conjugation reaction mixture was chilled at -80°C for 30 minutes then centrifuged at 4°C for a further 30 minutes. The resulting liquid phase was drawn off with a pipette, vacuum evaporated until dry and then resuspended in 50 µL of deionised water. The solid pellet (if any) was directly resuspended in 50 µL of deionised water. Both samples were then analysed with PAGE alongside a sample from the initial reaction mixture to determine the extent of separation.

References

- Gangaraju Vamsi K. Lin Haifan. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2009; 10 (2) (1) p. 116-125.

- Stephanopoulos N, Francis MB. Nat Chem Biol. 2011; 7 (12) p. 876-884.

- Hermanson G. Academic Press; 2013.

- Antos JM, Francis MB. J Am Chem Soc. 2004; 126 (33) p. 10256-10257.

- Jones MW, Mantovani G, Blindauer CA, et al. J Am Chem Soc. 2012; 134 (17) p. 7406-7413.

- Mason A, Thordarson P. J Vis Exp. 2016; (113).

- Sechi S, Chait BT. Anal Chem. 1998; 70 (24) p. 5150-5158.

- Reddington S, Howarth M. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2015; (29) p. 94-99.

- Goodman RP, Erben CM, Malo J, et al. ChemBioChem. 2009; 10 (9) p. 1551-1557.

- Bornhorst J, Falke J. Methods Enzymol. 2000; 326 p. 245-254.

- Williams B, Chaput J. Curr Protoc Nucleic Acid Chem. 2011; (480) p. 1-29.

- Shafer DE, Inman JK, Lees A. Anal Biochem. 2000; 282 (1) p. 161-164.

- Williams B, Chaput J. 2011; (480) p. 1-29.

- Simpson DM, Beynon RJ. J Proteome Res. 2010; 9 (1) p. 444-450.