Introduction

In order to gain a fundamental understanding of the self-assembly of the HIV capsid, it is crucial to characterise the reaction kinetics of the system. Biolayer Interferometry allows for quick, accurate kinetic experiments to be completed.

BLItz is an alternative means of obtaining kinetic data to SPR, which was also utilised throughout the project. You can check out our SPR data here! BLItz was often easier to access, and quicker to set-up, than SPR. Whilst SPR is an automated system, BLItz is largely manual.

Figure 1: A schematic diagram of the Biolayer Interferometry mechanics. Proteins, or other subunits (red) bind to DNA template binding sites. The change in properties observed in the reflected white light is output as a change in biolayer over time.

BLItz is a label-free way to measure nano-scale binding events between nucleic acids and proteins in real time. A highly fragile glass tip contains a biosensor on which reaction takes place. As white light passes through the optical fibre tip, it is reflected back at the biolayer interface.

However, chemistry at the surface of the biocompatible layer allows anchor to be bound. Subsequently, we were able to attach various DNA structures to the surface, and facilitate interactions between the DNA structures and our HIV-1 capsid proteins. This surface layer will alter the refractive index, and thus the final intensity, of the reflected light. BLItz analyses this change in wavelength and outputs a live binding curve.

Aims

Whilst BLItz serves as a fantastic means by which to test binding events more generally, due to time constraints BLItz was used to provide evidence for a working hypothesis. We suspected that our discrete cross-linked hexamer 6His (A14C/E45C) bound to single-stranded and double-stranded DNA. We had also produced preliminary data indicating that monomeric CA-6His protein (W184A/M185A) bound to single-stranded DNA. Take a look at all this data, and more, over on our SPR page. The following BLItz experiments sought to test this hypothesis.

Methodology

A Biolayer Interferometry optimisation buffer was prepared and diluted for use during BLItz experimentation. The BLItz biosensor tips were soaked in the buffer for a number of hours prior to any runs to remove a preservative coating and to equilibrate the tip. Monomeric CA-6His proteins, and discrete cross-linked hexamer 6His proteins, were diluted to a similar concentration using the optimisation buffer following buffer exchange. If you want to know how we produced these proteins, you’ll want to check out our Protein Engineering page! Single stranded and double stranded DNA linear templates had been prepared so as to bind to an anchor. The following BLItz protocol was used.

|

Time (s) |

Step |

Description |

|

30 |

Baseline |

Tip placed in BLItz buffer |

|

240 |

Loading |

Tip placed in anchor |

|

60 |

Baseline |

Tip placed in BLItz buffer |

|

360 |

Loading |

Tip placed in DNA template |

|

120 |

Baseline |

Tip placed in BLItz buffer |

|

180 |

Loading |

Tip placed in Protein |

|

120 |

Dissociation |

Tip placed in BLItz buffer |

This was accompanied by the following materials

- Monomeric CA-6His protein (Buffer exchanged, 250 , 0.17mg/mL)

- Discrete cross-lined hexamer 6His protein (Not buffer exchanged, 250 , 0.241mg/mL)

- Anchor (250 , 100nM)

- ss DNA (250 , 100nM)

- ds DNA (250 , 100nM)

Results

Experiment 1: Hexamer Binding

The aim of our hexamer experiments was to determine whether the cross-linked hexamer would natively bind to single stranded or double stranded DNA.

The binding curves observed in the interaction between discrete cross-linked hexamer proteins and ss/ds DNA strongly indicates some sort reaction. Whilst the sharp spike at the point of protein addition is likely to be systematic, the following exponential binding/un-binding events are consistent with the hypothesis that the discrete cross-lined hexamer protein binds to both single and double stranded DNA.

If hexamers are capable of binding to both single stranded and double stranded DNA, this could serve as a fantastic means through which to test future assembly experiments. This could also help to explain in vivo capsid construction; perhaps hexamers and pentamers, once formed, localise on DNA or RNA to facilitate self-assembly.

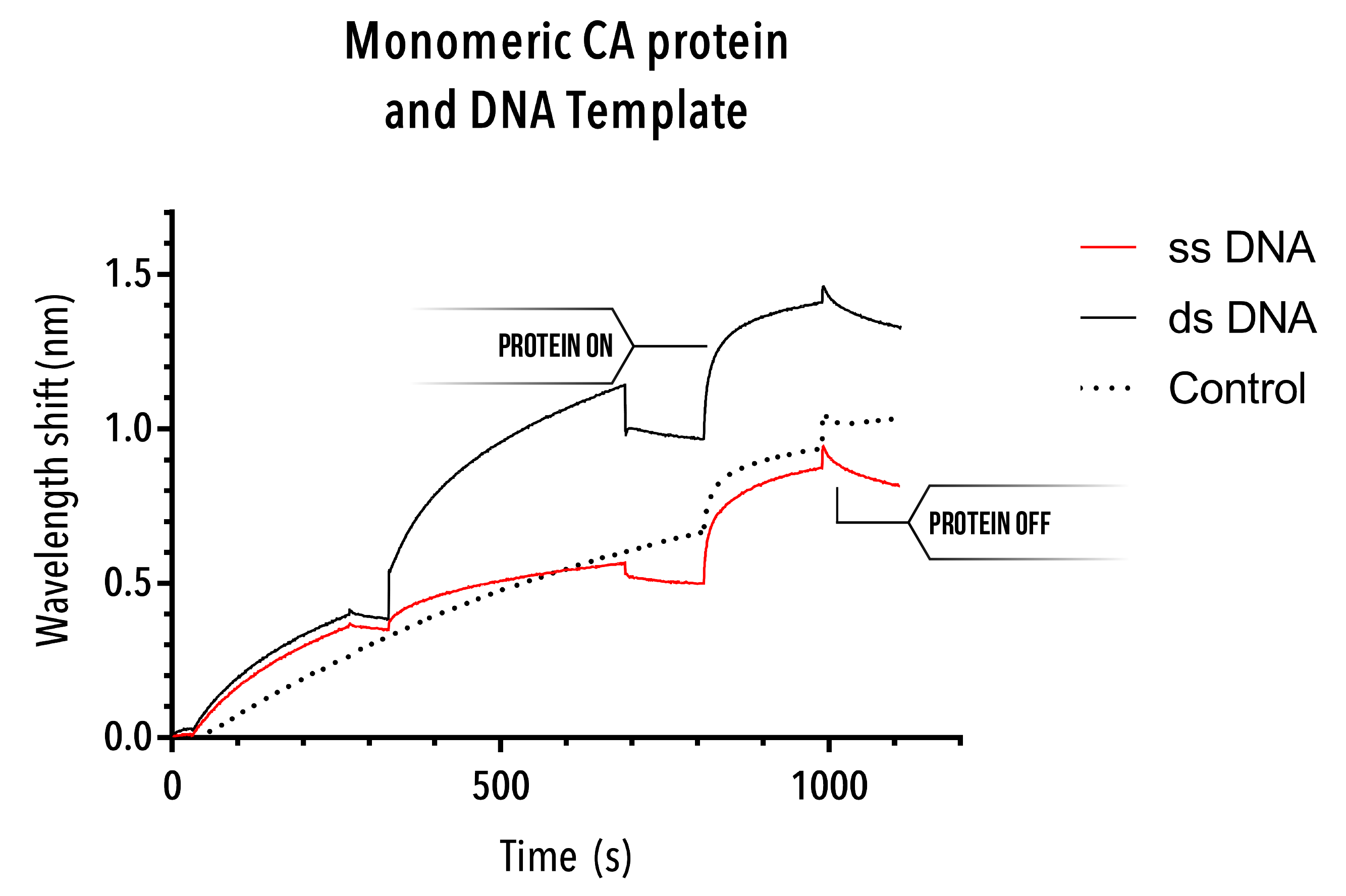

Experiment 2: Monomer Binding

Unfortunately, due to the inability to extract a useful control experiment, the monomeric CA protein binding curves are not particularly helpful. Whilst binding appears to occur at the point of protein addition, the control curve (which inexplicably rising over time, despite only buffer being used) also shows a similar binding curve. As such, at the very least, this BLItz experiment does not provide evidence for monomeric protein interaction with single stranded or double stranded DNA.

Whilst an interesting avenue of research, this outcome would be preferential for our experiments. If our protein consistently interacted with single stranded and/or double stranded DNA, we would be unable to use DNA scaffolds as our vehicle of assembly. Take an in-depth look at our DNA scaffold here. Non-specific binding would discredit any quantitative data established.

Conclusion

BLItz allowed us to quickly test the binding of hexamer protein structures to single stranded and double stranded DNA. Our hypothesis was that discrete cross-linked hexamers would bind to a linear DNA template. The above BLItz results strongly support such a hypothesis, and give evidence for both a binding and unbinding phase for self-assembled hexamer proteins.

This finding is particularly interesting given the in vivo application of such a binding event. Proteins, having formed hexamers and pentamers, natively interact so as to form the complex three-dimensional fullerene cone of the capsid. As the local concentration of hexamerised proteins increase, the likelihood of capsid self-assembly increases. This result suggests that there may be complex binding phenomena within the Virus that results in hexamers localising on DNA or RNA. There is also some evidence regarding the mechanism of binding between the discrete cross-linked hexamer protein and DNA. It is suggested that DNA nucleotides are attracted to the positively-charged centre of the hexamer structure. Having come into close proximity with each other, a seeding event may occur, and the capsid may begin to construct.

References

- Shah, N. and Duncan, T. Bio-layer Interferometry for Measuring Kinetics of Protein-protein Interactions and Allosteric Ligand Effects J Vis Exp (2014) 84