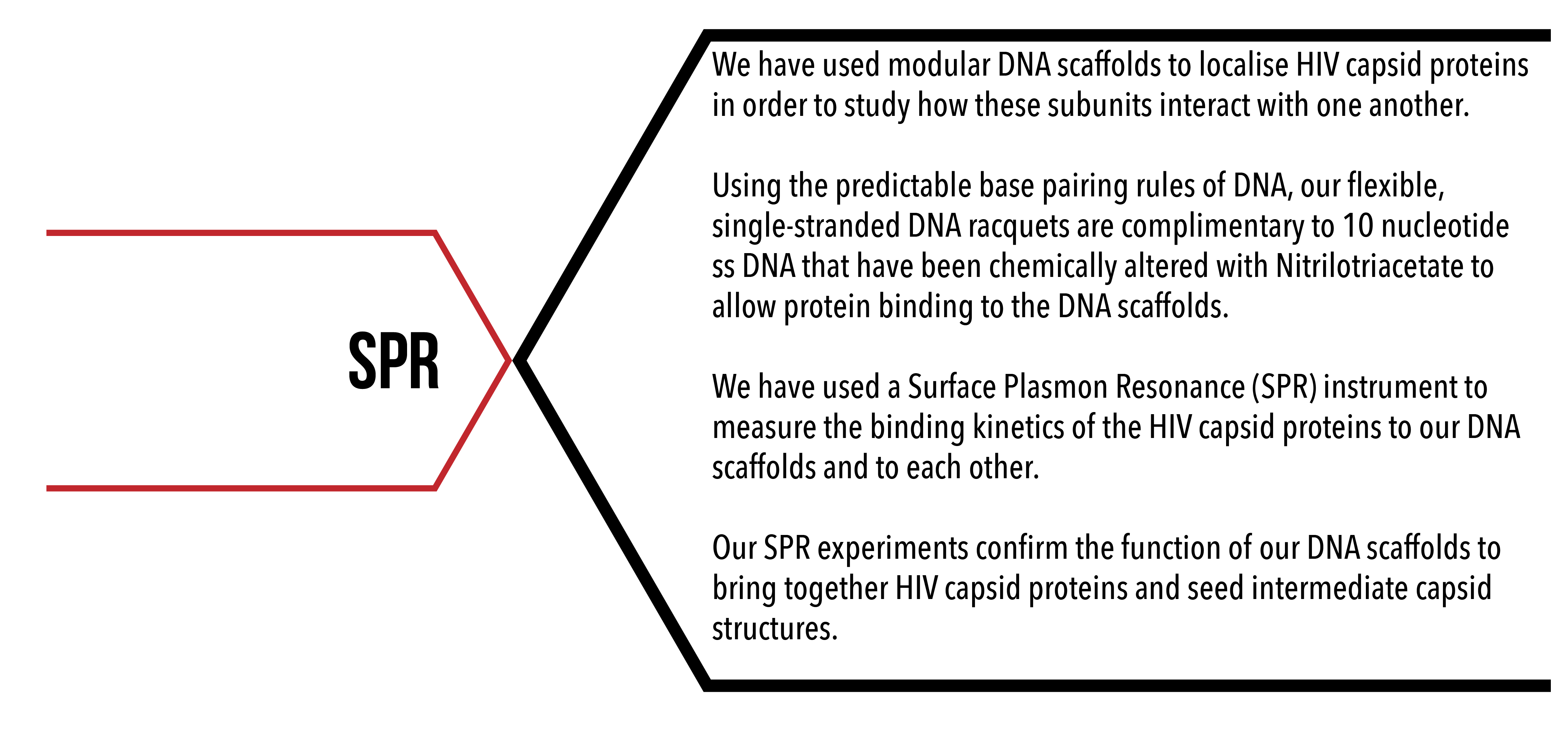

Introduction

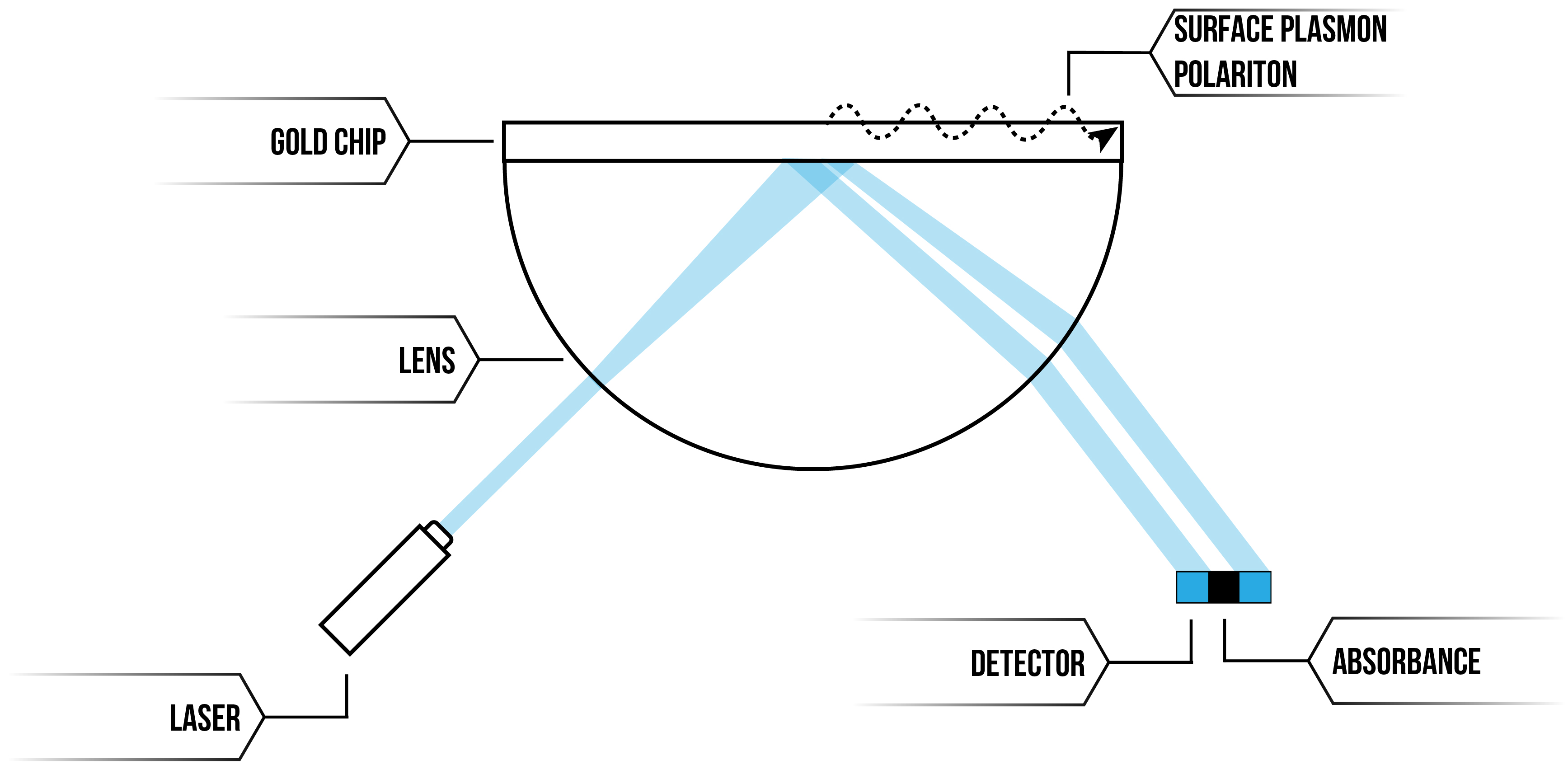

Surface plasmon resonance (SPR) is a phenomenon that occurs when focused light strikes metal surfaces at a particular angle. At a certain angle of incidence, light reflected off the metal surface has a graded reduction in its intensity and this reduction can be measured 1. SPR instruments exploit this phenomenon, allowing for quantifiable, label-free, real-time detection of molecular binding by mass on the nano-scale (see figure 1 for schematic diagram), with sensitivity in the picogram per mm2 range 2.

The assembly of the HIV capsid is governed by the interactions of its individual protein subunits – but the mechanisms by which they coordinate this behaviour is unknown. Obtaining quantitative data for HIV-1 CA protein binding to its neighbours is paramount in deriving the binding affinity that CA proteins have to each other. We can use SPR to indirectly measure binding of CA proteins to each other. Knowing the rate of association and dissociation of CA proteins to each other will lead not only to fundamental understanding of HIV capsid self-assembly, but also to greater understanding of molecular-self assembly more generally, and to new techniques to test HIV capsid-disrupting peptides.

Figure 1: SPR instrument illustration

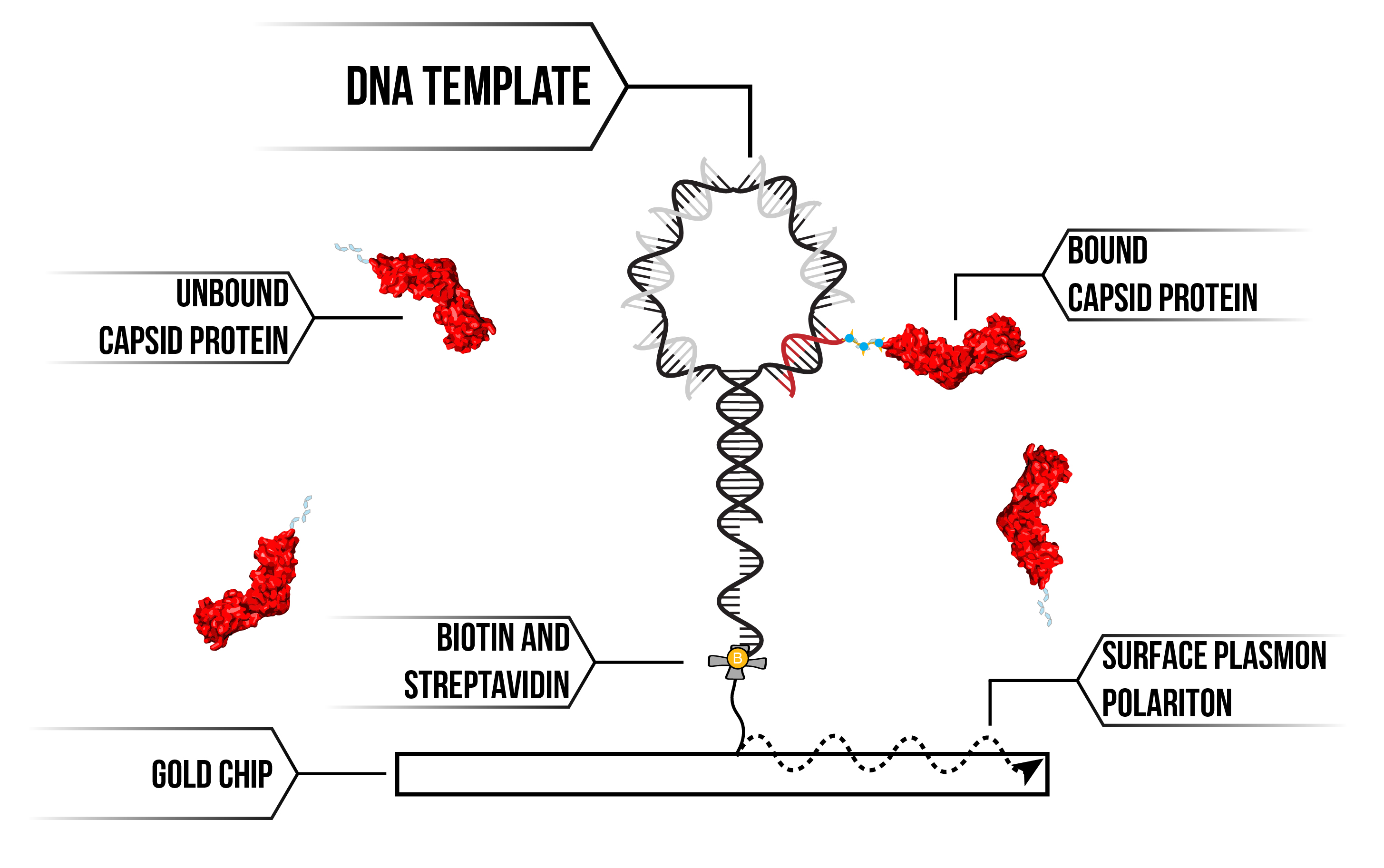

We can detect binding and unbinding of CA proteins by using our DNA templates to attract proteins on the Biacore SPR System via an interaction between proteins with polyhistidine (6His) residues with Nickel-NTA-DNA (see figure 2). By increasing the localised concentration of CA proteins by bringing them together on our DNA scaffold, we can obtain data on protein-protein interactions that would otherwise not be possible in vitro.

Figure 2: SPR DNA template and CA protein attachment.

We functionalised a gold-plated CM5 chip for use in our Biacore SPR instrument using streptavidin/biotin chemistry. This combination of surface chemistry provides a means to anchor DNA templates to the surface. First, we add a biotinylated 15 base DNA anchor to the surface, then flow on DNA racquet scaffolds that contain complementary 15 base overhang. We are then able to flow on the protein of interest and observe for binding. Binding of biological material to the DNA racquet is detected as a phase shift in light reflected off the chip's surface, with the distance of the phase shift corresponding to the mass of material that binds. Using SPR we can detect binding and unbinding of CA proteins to our DNA racquet template under a number of different conditions 3. Analysing this data and using it to parameterise our mathematical models, we can derive the rates of association (kon) and dissociation (koff) for both the attachment chemistry of the 6His tag and subsequently the binding of the capsid protein to itself.

Aims

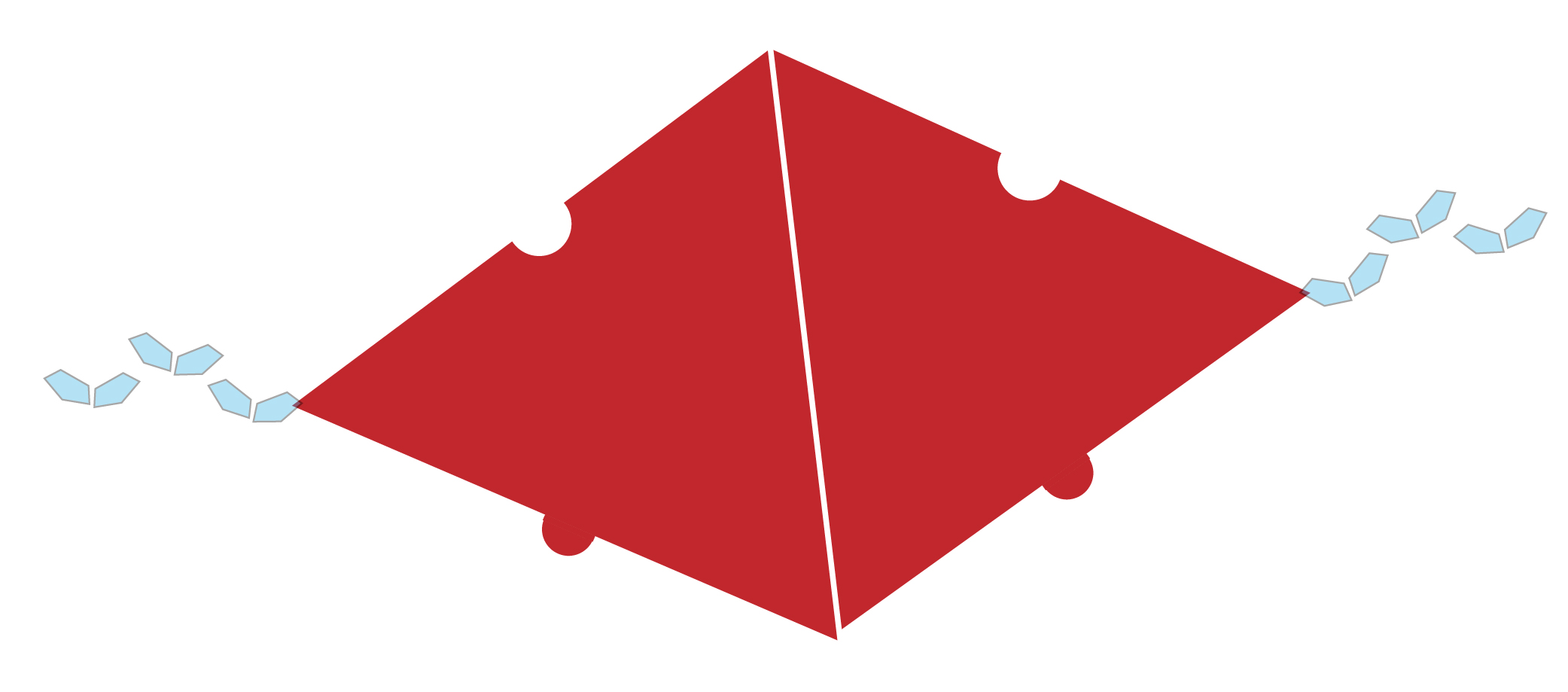

- To synthesise novel, modular DNA origami racquets capable of capturing CA proteins in hexameric or pentameric configurations.

- To measure the interaction rates between protein subunits to the scaffold and each other using surface plasmon resonance.

- To induce hexamer formation from individual capsid proteins.

To realise these aims, we have utilised DNA design and protein engineering to allow us to conjugate HIV capsid proteins to a rationally designed DNA scaffold. We are then able to measure and obtain quantitative data on the molecular binding events of the capsid protein using an SPR instrument

Materials and Methods

DNA template synthesis:

Using the specificity of DNA base-pairing, we were able to form two rationally designed DNA scaffolds for templating the synthesis of HIV capsid pentamers and hexamers

Racquet and linear DNA sequences (IDT) were rehydrated to 100 µM in MilliQ water. Templates were synthesised at 1 µM in 50 µL hybridisation buffer (Table 1), with 10 base pair “blocking” DNA strands to block off binding sites or functionalised nitrilotriacetate modified DNA (NTA-DNA) added at 2 uM concentration to ensure saturation of the DNA template.

DNA templates were annealed in a thermocycler in the following program:

- 95°C for 3 minutes

- 70 cycles of -1°C per minute fron 95 to 25°C

- 10°C hold.

Annealed DNA templates were stored in -20°C fridge and used within 72 hours.

Before use, synthesised DNA templates were imaged on native 10% polyacrylamide (PAGE) gels (Table 2). Synthesised DNA templates were loaded onto the native PAGE gels at 200 nM (2 µL 1 µM DNA sample, 3 µL MilliQ water and 5 µL native loading dye, see Table 3).

SPR protocol

Prior to first use, we customised one of four microfluidic channels of a gold plated CM5 chip (GE) to with streptavidin-biotin chemistry, which allows us to attach our protein-capturing DNA templates.

For each run, our customised CM5 chip (GE) was loaded into the SPR instrument and primed with modified, 0.22 µM filtered buffer (Table 4).

The system was equilibrated with modified HBS-P buffer to ensure the SPR instrument and chip were properly primed for use.

DNA templates at 500 nM were attached to biotinylated DNA in flow cell 2 at a capture rate of 10 µL min-1 for 60 seconds, followed by proteins (see Protein Constructs) at 5 µM in modified HBS-P buffer (unless otherwise specified) were flowed on at a rate of 40 µL min-1 for 180 seconds, followed by a dissociation of 300 seconds before 2x regenerations of the chip and removal of the DNA template and protein using regeneration buffer (pH 2.5 0.01M glycine) at 10 µL min-1 for 60 seconds each time, followed by rinsing the microfluidic channel with running buffer before starting the next run.

A bacterial type III secretion system protein LcrV was used a as a positive control for Nickel-NTA-DNA binding because it has been well characterised at UNSW’s Lee Lab.

Buffer exchange

Prior to use, proteins snap-frozen in 10% glycerol were thawed, buffer exchanged at 99.9% purity into modified HBS-P buffer in Bio Rad P6 Micro Bio-Spin Chromatography 6 Columns as per manufacturers instructions. Buffer exchange was repeated a second time for proteins originally in buffer containing EDTA to avoid chelation of nickel in NTA-DNA binding.

Nickel-NTA incubation

DNA racquets containing NTA-DNA required incubation for one-hour prior to use to allow Nickel to bind to the NTA of the NTA-modified DNA. 50 µL 1 µM annealed racquets in hybridisation buffer were incubated with 6 µL 1M NiSO4 per 10 base pair NTA-DNA site (ie 6 µL for racquets with one NTA-DNA site, 36 µL for racquets with 6 NTA-DNA sites) and modified HBS-P buffer to a total of 100 µL.

DNA template synthesis

For details of the DNA template synthesis, see our page on DNA Origami

SPR Buffer

|

Chemical |

Concentration |

|

HEPES |

10 mM |

|

NaCl |

40 mM |

|

MgCl2 |

20 mM |

|

TWEEN |

0.05% |

Table 4: Modified HBS-P buffer

Protein Constructs:

Dimer: C-terminal 6His – HIV-1 capsid (CA) protein with polyhistidine tag for conjugation to DNA. This protein, like the wild-type protein, naturally dimerises in solution.

Monomeric: (W184A/M185A, C-terminal 6His) – HIV-1 CA with a mutation that increases the propensity for the protein to remain monomeric in solution and with a polyhistidine tag for conjugation to DNA.

Dimer disrupted 6His fractions: (W184A/M185A, C-terminal 6His) – Three other fractions of the above monomeric protein constructs were obtained before and after elution using size exclusion chromatography:

Dimer fraction: CA proteins that eluted at 52 kD, a size consistent with dimerised capsid proteins, assumed to be a mixture of monomer and dimer protein, used at a concentration of 3.4 µM.

Hexamer fraction: CA proteins that eluted at ~ 156 kD, consistent with hexamer structures that can cross-link to form intermediate capsid structures used as a concentration of 500 nM.

Mixed fraction: CA proteins that did not undergo size exclusion and so contained a mix of the above two protein fractions along with monomeric protein.

Discrete cross-linked hexamer: A14C/E45C/W184A/M185A – Discrete cross-linked hexamer CA protein with dimer disruption, resulting in hexameric proteins that do not cross-link into larger structures.

LcrV: C-terminal 6His – LcrV is a bacterial type III secretion system protein found in Yersinia pestis. Previous work using 6His-modified LcrV on analytical instruments including SPR in the Lee Lab makes it a suitable positive control to check Nickel-NTA binding of proteins to DNA.

Results

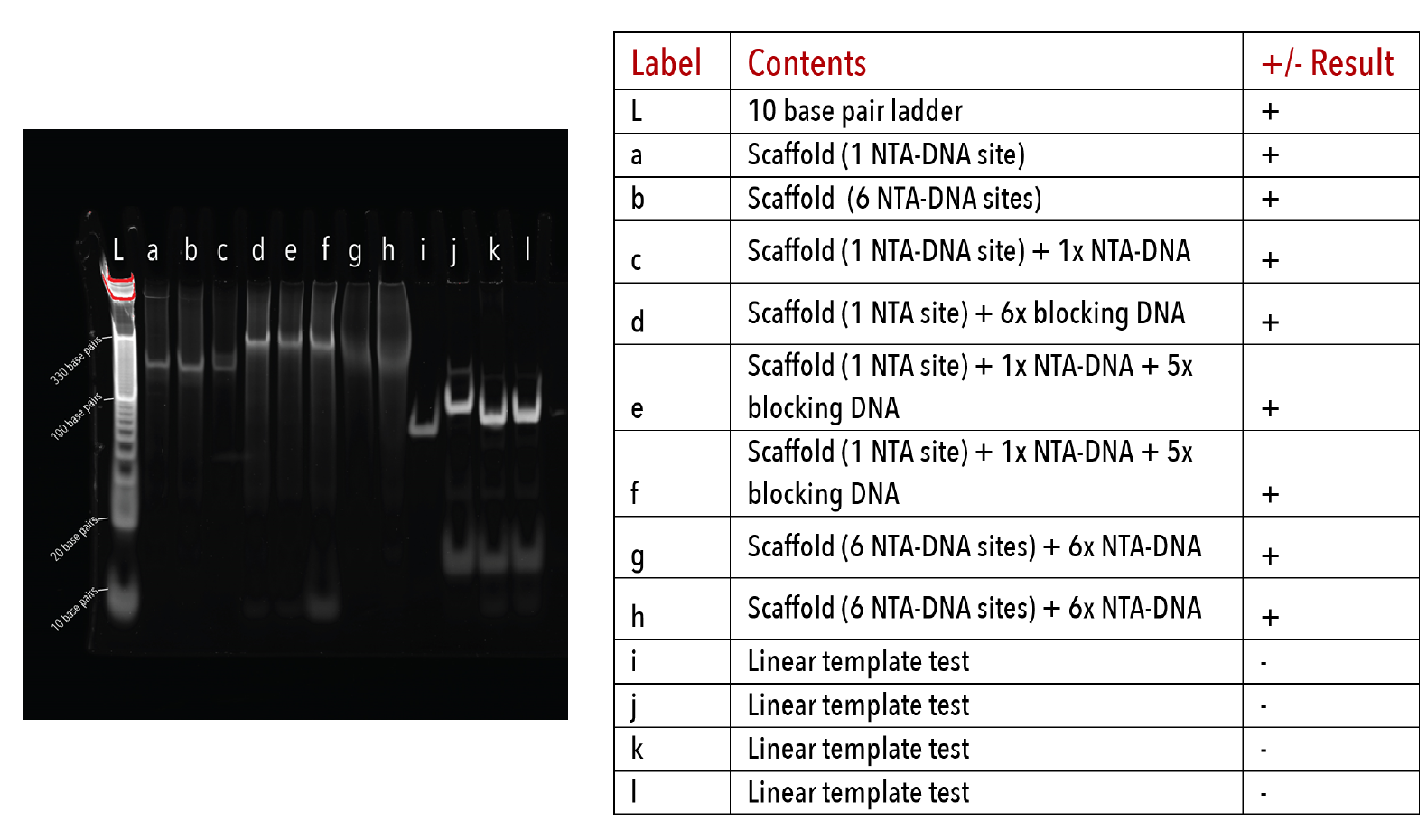

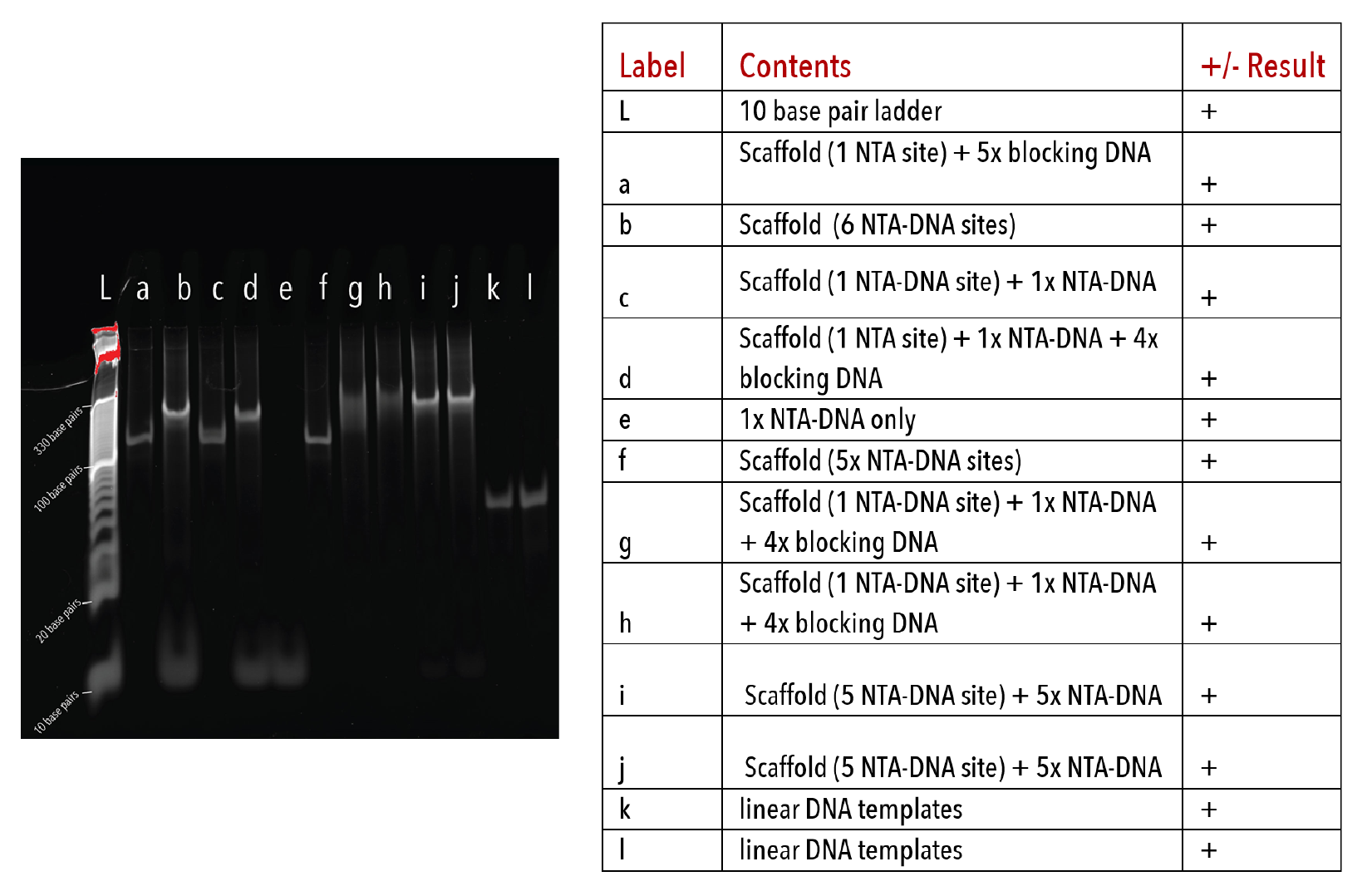

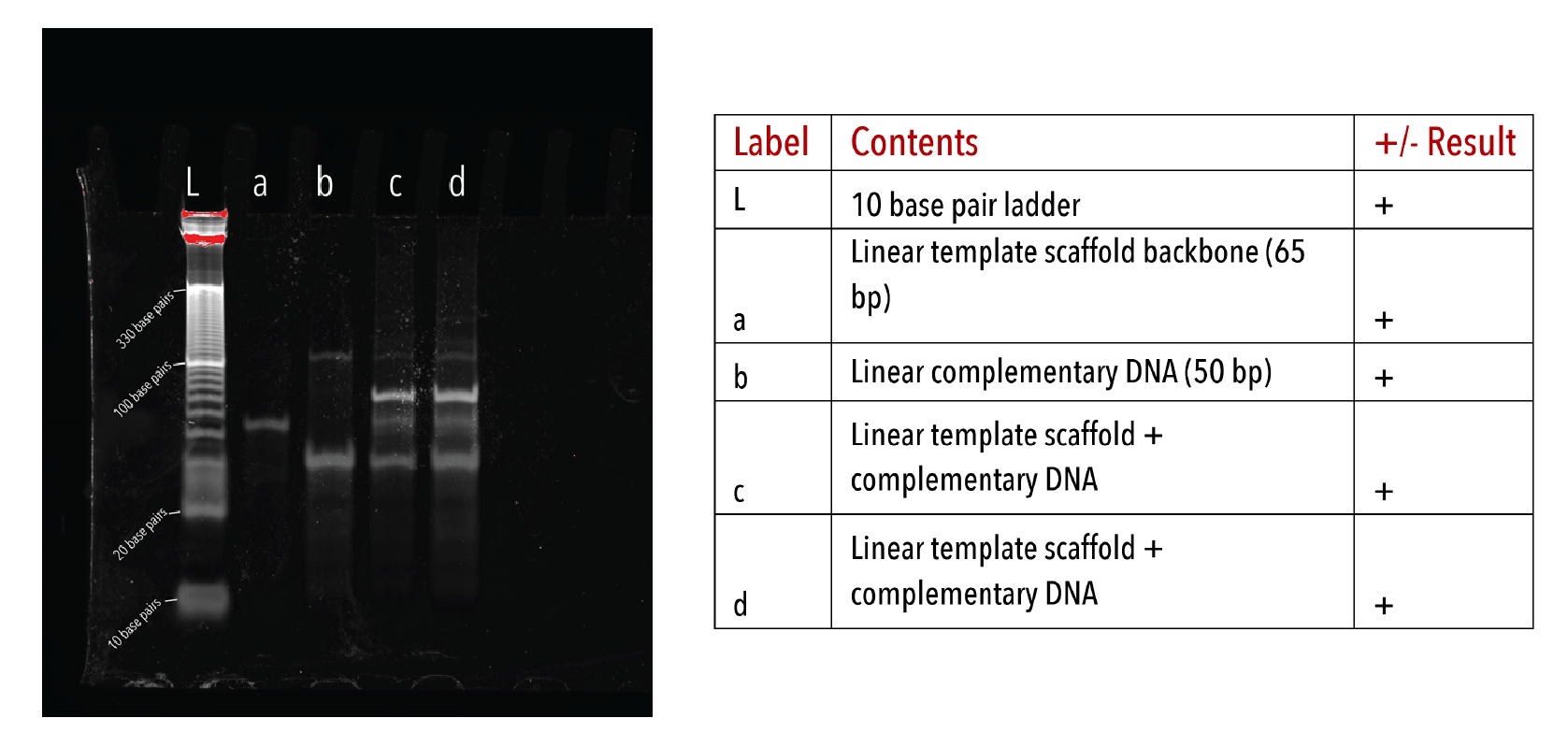

Size confirmation of DNA origami racquets

We determined whether DNA templates had formed properly by visualising on native PAGE after annealing. Formation of the DNA template alters and size of the DNA scaffold, resulting in a corresponding retardation in band migration.

This was apparent for all DNA templates used in later kinetic experiments (Figures 3-5). Moreover, there was an absence of multiple products or smeared bands, indicating successful annealing with full occupation of sites.

Figure 3: Hexamer DNA racquets on a 10% native PAGE gel. The gel was run at 180V for 45 minutes at 4°C in 1x TAE buffer, stained with Sybr-Gold for 10 minutes and imaged on a UV-transilluminator.

Figure 4: Pentamer racquets on a 10% native PAGE gel. The gel was run at 180V for 45 minutes at 4°C, stained with Sybr-Gold for 10 minutes and imaged on a UV-transilluminator.

Figure 5: Linear DNA templates on a 10% native PAGE gel. The gel was run at 180V for 45 minutes at 4°C, stained with Sybr-Gold for 10 minutes and imaged on a UV-transilluminator.

SPR results

Experiments 1-6: Binding of CA proteins to NTA-DNA racquets

We wanted to test whether our DNA template racquets were able to bind proteins at all, and if so, which protein constructs were able to do so. We also wanted to test if our racquet constructs with six NTA-DNA templates were able to bind six proteins, compared to the single NTA-DNA site containing racquets only capable of binding one protein.

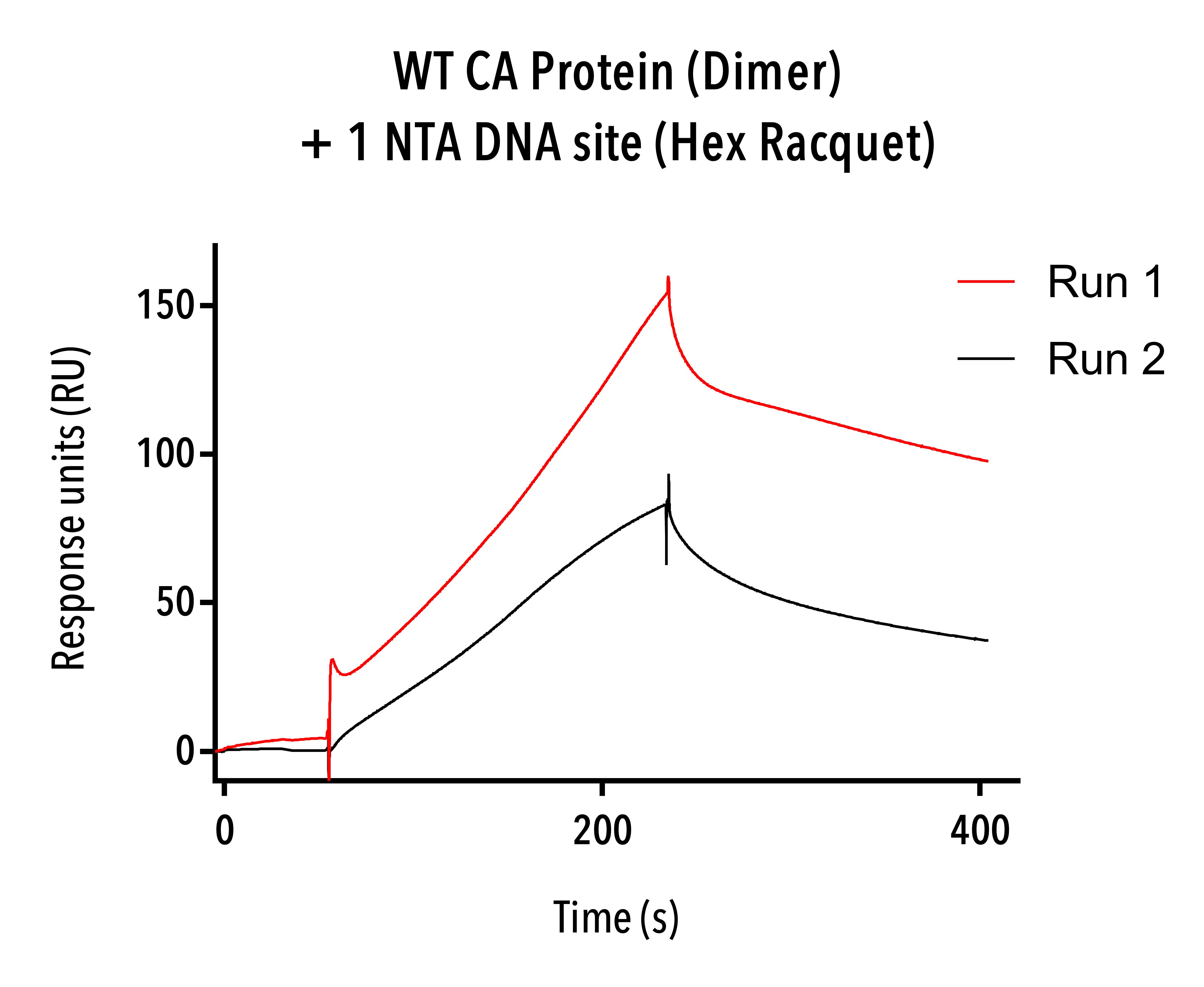

1. Dimer

Dimer proteins (C-terminal 6His) were tested on the Biacore SPR instrument for binding to a Hexamer racquet with one NTA-DNA site and single-stranded DNA racquet templates. Given the number of NiNTA sites, full saturation of NTA-DNA templates with one NTA-DNA site should result in around 36 response units (RU, with 1 RU = 1 pg mm-1 for all SPR data) based on streptavidin-biotin coupling of the SPR chip.

However, 144 and 190 response units were recorded respectively and the signal appeared far from maximal (see Figure 8), and no binding was evident in single-stranded DNA racquets.

This suggests that C-terminal 6His protein dimers are not suitable with our racquet design, but that our racquets may have seeded intermediate capsid protein structures. One caveat is that gel results for these two experiments confirmed that we did not have full hybridisation of our hexamer DNA racquets, and that some of the hexamer racquet templates would not have contained NTA-DNA binding sites and instead been partially single-stranded. Further experiments showed that some capsid protein constructs were able to bind DNA without any conjugation chemistry, so having a mix a of NTA-DNA and free DNA racquets have had a synergistic effect, with the NTA-DNA conjugation attracting capsids and allowing intermediate structures to form, which then bound to the single-stranded racquets.

Figure 8: Sensorgram data of dimer proteins (WT-6His) showing significantly higher and faster binding than expected.

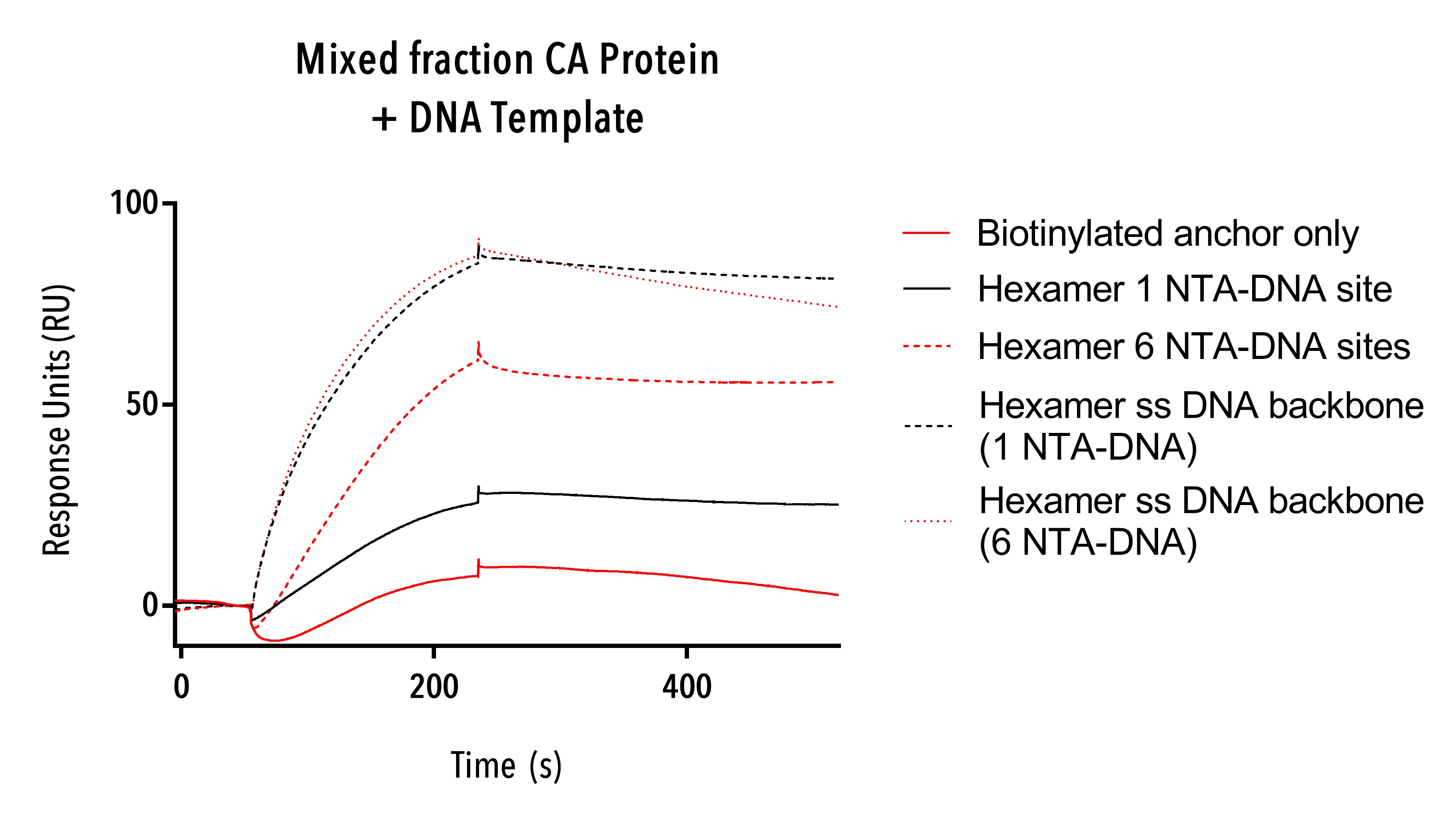

2. Mixed fraction

The mixed fraction of W184A/M185A, C-terminal 6His protein constructs was used on SPR with only the 15 base pair DNA anchor, Hexamer single-stranded DNA templates and hexamer racquets with one and six NTA-DNA sites.

The mixed fraction proteins showed strongest affinity to single-stranded DNA and some binding to hexamer racquets with one and six NTA-DNA sites (figure 9). Even our 15 base pair single-stranded biotintylated DNA anchor was bound by protein to a small degree, suggesting that some CA proteins intermediate structures have an affinity directly to DNA. This result led us to synthesise our linear DNA origami template to test this hypothesis.

While we may have had binding to our NTA-DNA sites on the racquets, it is hard to know whether this is specific or nonspecific binding because of the fact that single-stranded DNA racquet templates also showed a high degree of binding, and so we cannot say for sure from this experiment that mixed-size fractions of W184A/M185A, C-terminal 6His protein binds to our DNA racquets via the NTA-DNA sites.

Figure 9: Sensorgram of a mixed fraction of W184A/M185A, C-terminal 6His CA protein binding to hexamer racquet templates.

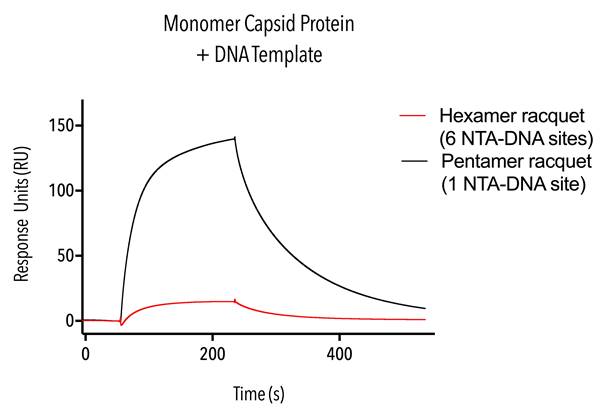

3. Monomeric.

Samples containing a uniform population of monomeric capsid protein (W184A/M185A, C-terminal 6 His) were tested on hexamer racquets with six NTA-DNA sites and pentamer racquets with one NTA-DNA site, and hexamer single-stranded DNA racquet templates.

Binding and dissociation of CA Monomer proteins to NTA-DNA containing racquet was evident (see figure 10). These curves appear to be consistent with published literature showing 6His NTA-DNA binding 4.

These results show that our racquet templates are indeed able to bind protein via NTA-DNA conjugation as we had hoped. DNA origami racquets may have been mixed up for this run – the pentamer racquet with one NTA-DNA site shows roughly six times bound capsid protein than the hexamer racquet with six NTA-DNA sites, with the simplest explanation being that the racquets were loaded in each other’s place in the SPR instrument. Unfortunately, the very last of the uniformly monomeric capsid proteins were used up in this experiment and so we couldn’t repeat the test under the same conditions to confirm this result.

Figure 10. Sensorgram of monomer capsid proteins.

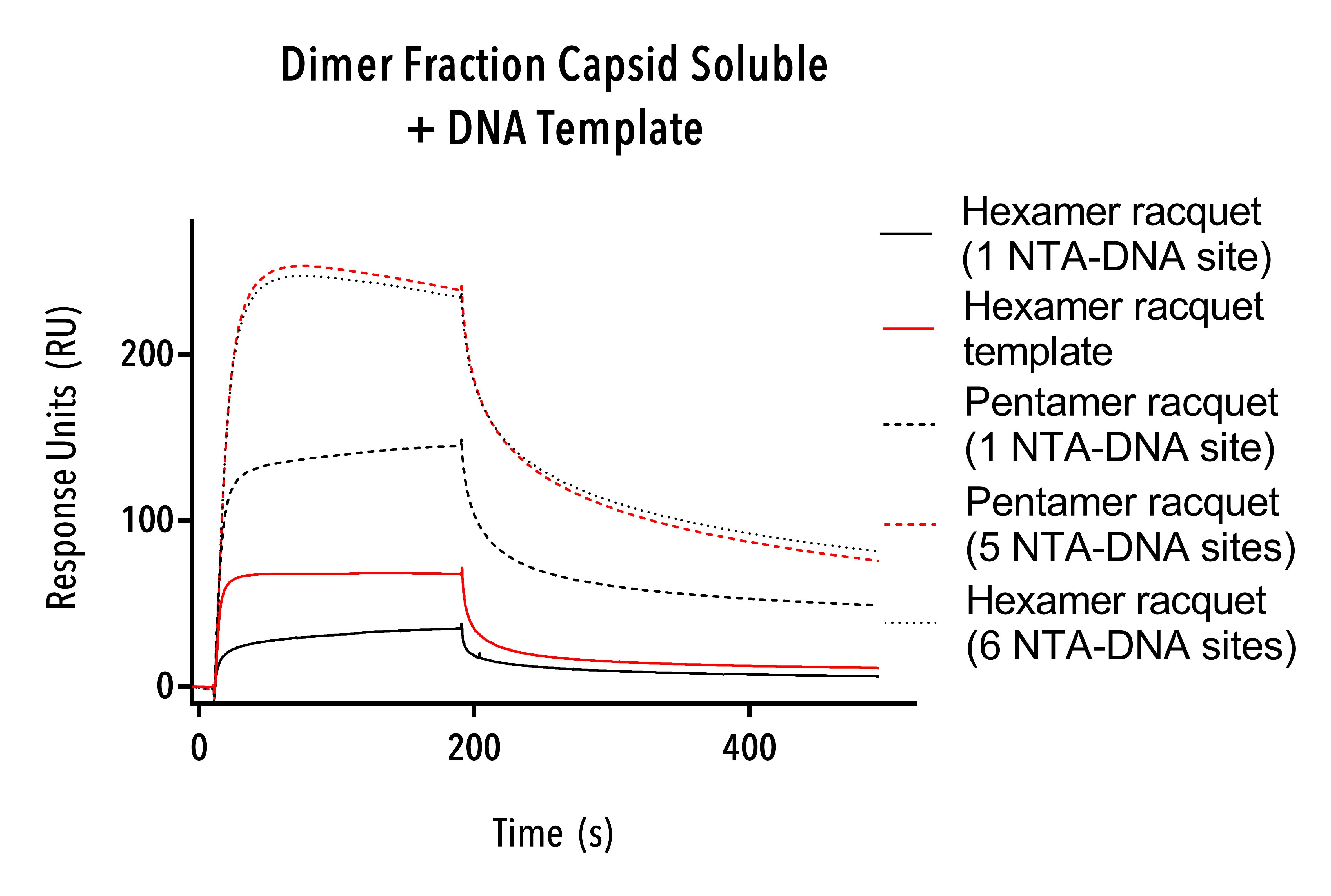

4. Dimer fraction

Dimer fraction (W184A/M185A, C-terminal 6 His) proteins were tested using hexamer single-stranded DNA templates, hexamer racquets with one and six NTA-DNA sites and pentamer racquets with one and five NTA-DNA sites.

The results from this experiment show that the pentamer racquet with five NTA-DNA sites and the hexamer racquet with six NTA-DNA sites are able to bind significantly more protein than their one NTA-DNA containing counterparts (figure 11).

The stoichiometry between the racquet templates is not exactly as expected (five and six times more binding, respectively) but nonetheless this result adds to previous the previous result (figure 10) to confirm the function of our rationally designed DNA racquet templates to bind HIV CA proteins via NiNTA-DNA conjugation.

Further work to optimise buffer and SPR setup conditions could help tune our racquets to work exactly as we had hoped.

Figure 11: Sensorgram of dimer fraction protein (W184A/M185A, C-terminal 6 His).

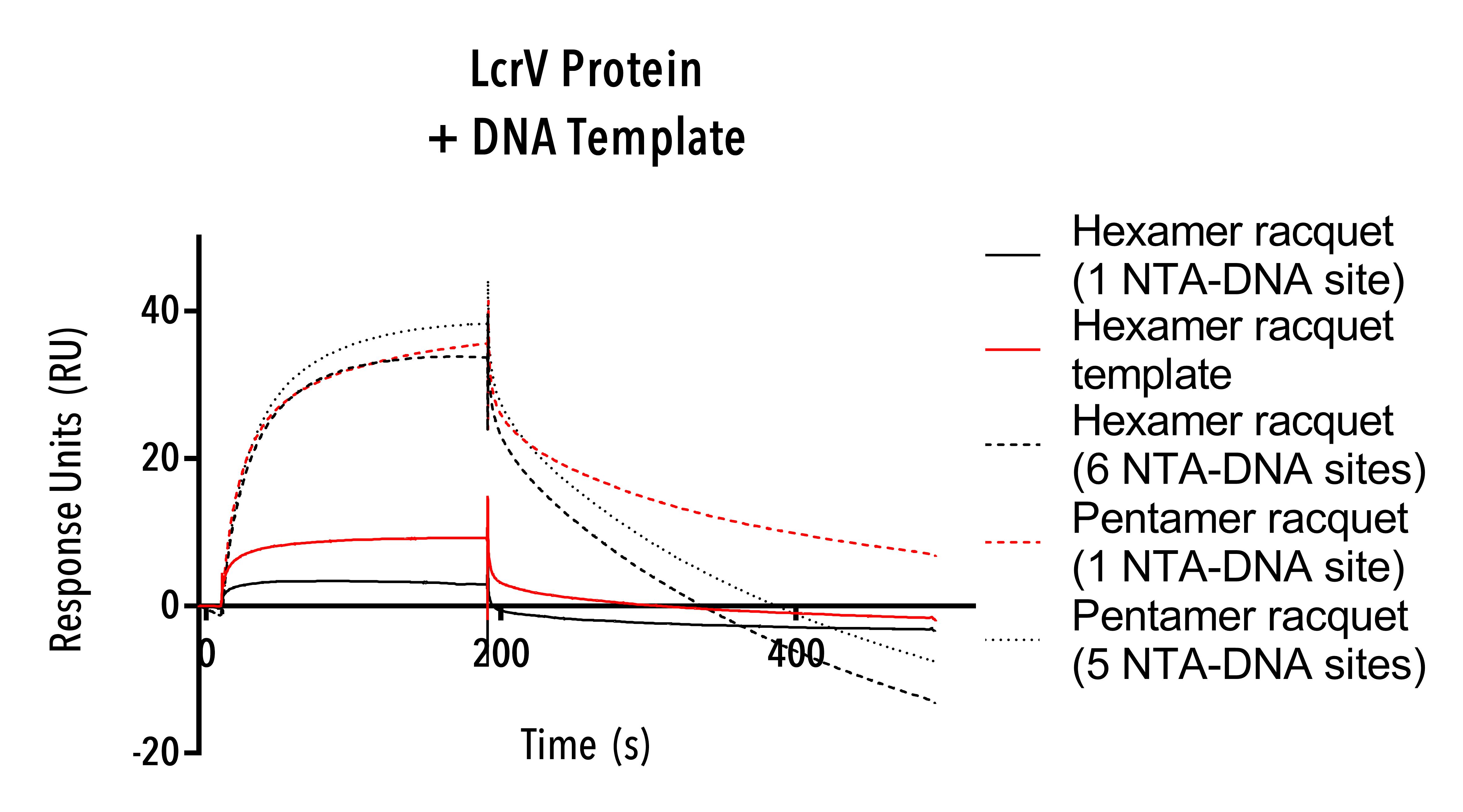

5. LcrV

LcrV (C-terminal 6his) positive control proteins were tested using hexamer single-stranded DNA templates, hexamer racquets with one and six NTA-DNA sites and pentamer racquets with one and five NTA-DNA sites.

LcrV protein was bound in higher numbers to the pentamer and hexamer NTA-DNA racquets with five and six NTA-DNA sites as compared to the same length racquets with only one NTA-DNA site (Figure 12).

This result confirms our racquets as functional and able to bind polyhistidine-modified protein. Differences in response units between pentamer and hexamer racquets with one NTA-DNA site suggest further optimisation in our SPR protocol is required.

Figure 12: Sensorgram of LcrV protein.

Experiments 5 and 6: Binding of HIV CA protein to DNA

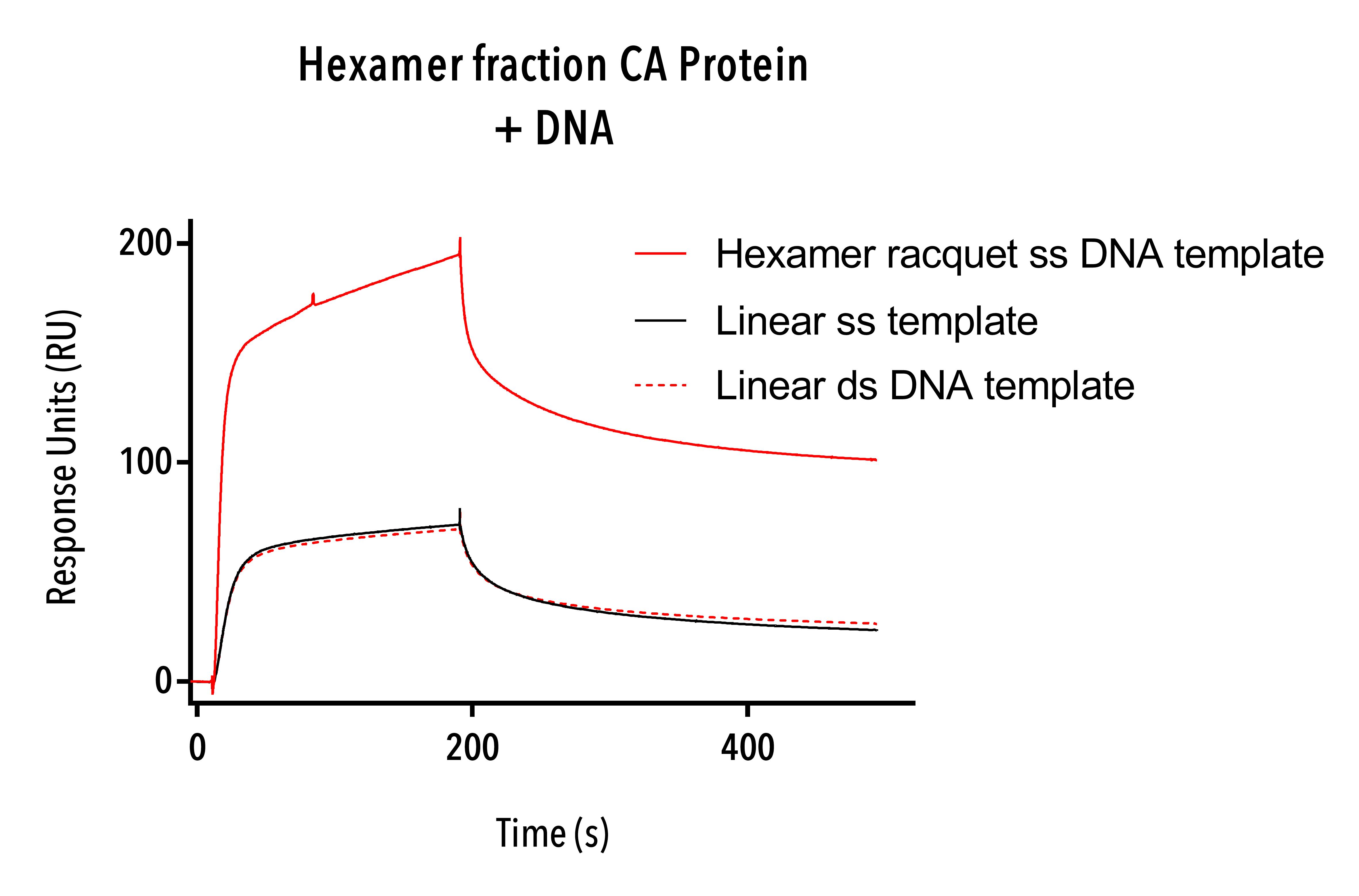

5. Hexamer fraction

Hexamer fraction (W184A/M185A, C-terminal 6 His) protein was tested using Hexamer single-stranded DNA templates and single- and double-stranded DNA templates. Because of scarcity of this fraction, 500 nM concentration of protein was used, 10-fold lower than other SPR experiments.

The hexamer fraction protein binds to hexamer single-stranded racquets and to linear single- and double-stranded DNA (Figure 13).

Even at this low concentration, the aggregation of capsid protein and likely formation of intermediate capsid structures is evident as shown by the high response units, with high binding activity particularly on the single-stranded hexamer DNA racquet (roughly 0.2ng/mm2). The hexamer fraction protein appeared not to have a particular affinity to double- versus single-stranded DNA, and this may be simply because the looped hexamer template is 129 base pairs long as compared to 65 for the linear template. While we cannot ascertain any information about how the protein is binding to DNA, we can conclude that even at very low concentration, HIV protein hexamers show an affinity to DNA and further work could try to determine exactly how the hexameric proteins bind to DNA.

Figure 13: Sensorgram of Hexamer fraction showing nonspecific binding to hexamer racquet template and single-stranded DNA templates.

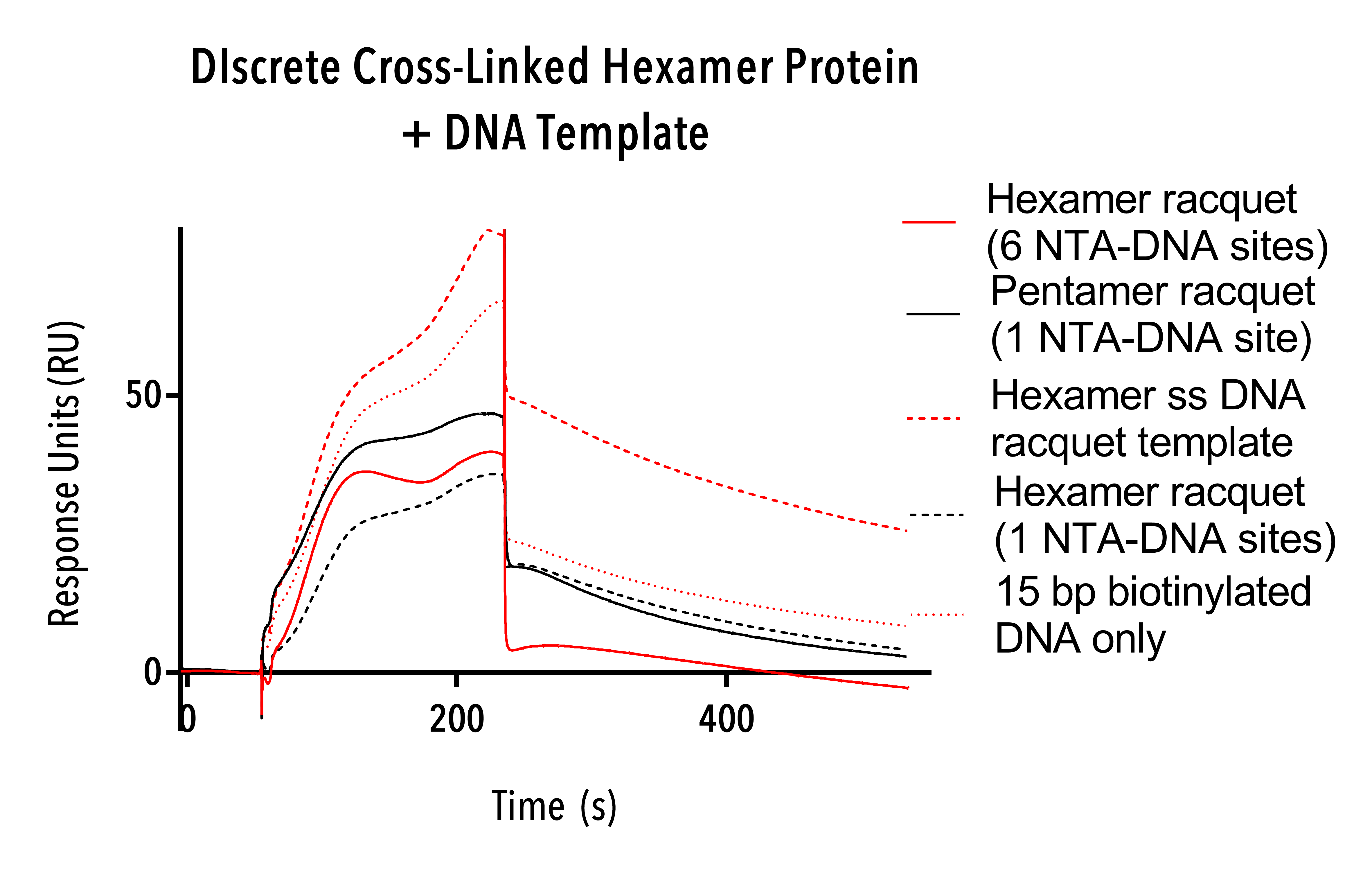

6. Discrete cross-linked hexamer (A14C/E45C/W184A/M185A).

Discrete cross-linked hexamer (A14C/E45C/W184A/M185A) were tested on the 15 base pair biotinylated DNA, hexamer single stranded templates, hexamer NTA-DNA racquets with one and 6 NTA sites and pentamer racquets with one NTA-DNA site.

The Discrete cross-linked hexamer proteins showed a consistent but irregular binding to all types of DNA including single-stranded scaffold DNA (see figure 14), to which it had the highest affinity, and fast, near-linear dissociation. These binding curves show non-specific binding to double- and single-stranded DNA and suggest that hexameric protein structures interact with DNA. This result in and of itself deserves further research as a mechanism for how HIV moves inside cells in vivo.

Figure 14: Sensorgram of Discrete cross-linked hexamer proteins showing nonspecific binding of capsid to all templates.

Conclusions

Novel single-stranded DNA origami racquets and linear templates were successfully synthesised and their predicted size before and after annealing NTA-modified DNA and complementary DNA confirmed on 10% native PAGE gels. Proof of concept of the ability of the racquets to localise protein binding using NiNTA-DNA chemistry was confirmed using SPR but only monomeric (W184A/M185A, C-terminal 6His) and dimer-fraction size-excluded (W184A/M185A, C-terminal 6His) CA proteins showed binding to our racquets without nonspecific binding. Racquet templates with more NTA-DNA sites were able to bind more CA protein but more work needs to be done to confirm whether that increase is exactly proportional to the number of NTA-DNA sites on the racquet templates.

Hexamer intermediate CA proteins appear to have an affinity directly to DNA and are able to seed larger intermediate structures with DNA acting as a seed. This was evident for both the discrete hexameric CA proteins and the hexamer fraction of the W184A/M185A, C-terminal 6His mutant CA proteins. Using SPR, we were able to confirm that we can measure the interactions rates between protein subunits to DNA scaffolds, and further work will allow us to extrapolate the binding affinity of the CA proteins to each other.

Further work to derive association and dissociation rates of HIV capsid protein interactions will continue at UNSW’s Lee Lab. Multi-capsid proteins were seeded on DNA racquets but further work, including testing with disruptive peptides, still needs to be done to confirm capsid protein conformation. If CA hexamer-disrupting peptides were able to prevent the binding of CA protein to racquets with 6 NTA-DNA sites we would be able to confirm that our racquet template is able to seed the formation of hexameric CA proteins.

We would also like to determine exactly how the hexamer CA proteins bind to DNA and for this we might test binding of Hexameric CA proteins to the phosphate backbone of DNA, and also to individual nucleotides in order to ascertain more information as to exactly how the protein-DNA binding occurs.

References

- Englebienne, P, Hoonacker, A, Verhas, M. Surface Plasmon Resonance: Principles, Methods and Applications In Biomedical Sciences. Spectroscopy, vol. 17, no. 2-3, pp. 255-273, 2003.

- Goodrich JA, Kugel JF. Binding and Kinetics for Molecular Biologists. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor; New York: 2007.

- Liu Y., Wilson W.D. Quantitative analysis of small molecule-nucleic acid interactions with a biosensor surface and surface plasmon resonance detection. Methods in Molecular Biology 2010; 613:1–23

- Drescher DG, Ramakrishnan NA, Drescher MJ. Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) Analysis of Binding Interactions of Proteins in Inner-Ear Sensory Epithelia. Methods in molecular biology (Clifton, NJ). 2009;493:323-343. doi:10.1007/978-1-59745-523-7_20.