INTRODUCTION

The process of turning protein design into functional units for use in analytical experiments requires that designed constructs, in the form of DNA sequences, are firstly cloned into vectors, and then expressed using E. coli. This section will describe the processes used to produce plasmids containing our mutated protein sequences. As outlined in our Protein Design section, we have designed a number of HIV-1 CA protein variants. These mutations enable:

- Formation of disulfide bond cross-links between proteins which stabilise hexameric and pentameric formations,1

- Inhibition of protein dimerisation,2

- Accessibility of residues for fluorophore conjugation, and

- Conjugation sites for reversible and irreversible chemistry.3,4

We were kindly provided a number of base constructs by Derrick Lau, upon which we added mutations in order to achieve the desired protein capabilities. The following proteins were provided within pET11a plasmids, inserts of which were found between BamHI and Ndel restriction sites:

- Wild type HIV capsid protein (HIV-1 CA wild type)

- Disulfide bond stabilised hexamer (HIV-1 CA A14C/E45C)

- Disulfide bond stabilised hexamer with C-terminal dimer disruption (HIV-1 CA A14C/E45C/W184A/M185A)

- Disulfide bond stabilised pentamer (HIV-1 CA N21C/A22C)

- Disulfide bond stabilised pentamer with C-terminal dimer disruption (HIV-1 CA N21C/A22C/W184A/M185A)

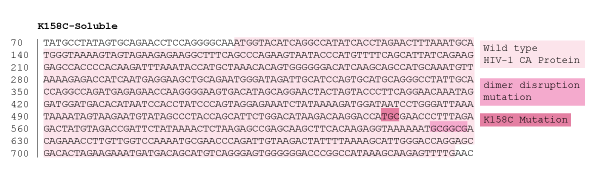

- Accessible cysteine on the N-terminus flexible loop (HIV-1 CA K158C)

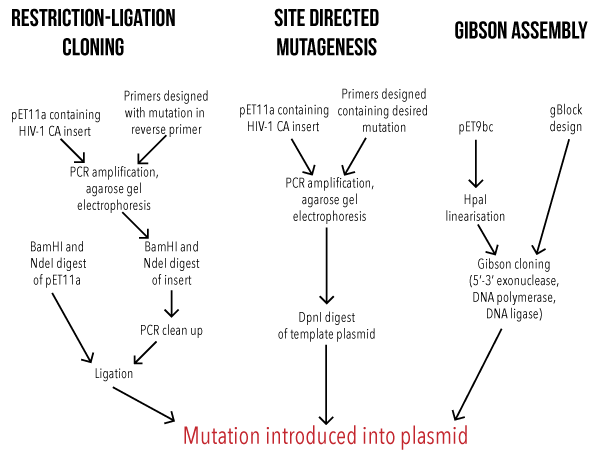

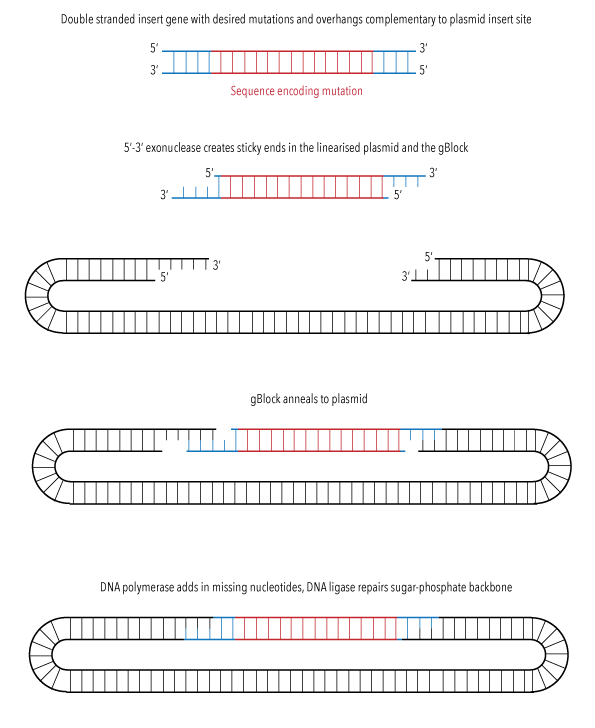

Mutations were added to these constructs by three cloning methods, overviews of which have been summarised in Figure 1:

- Restriction-ligation cloning, for addition of a 6-Histidine tag to the C-terminal of the proteins

- Site directed mutagenesis, for single nucleotide polymorphisms, and

- Gibson assembly, for the generation of large mutations.

Figure 1: Overview of cloning methods used to achieve HIV-1 CA mutant proteins

Aims

To successfully clone mutated HIV-1 CA protein sequences into E. coli, using three cloning methods:

- Restriction-ligation cloning

- Site directed mutagenesis

- Gibson Assembly

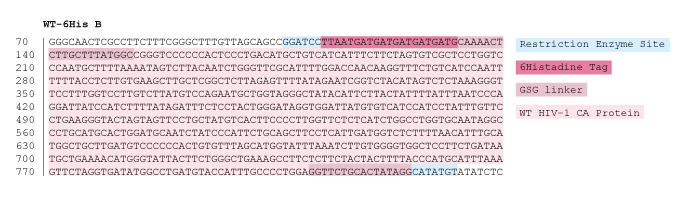

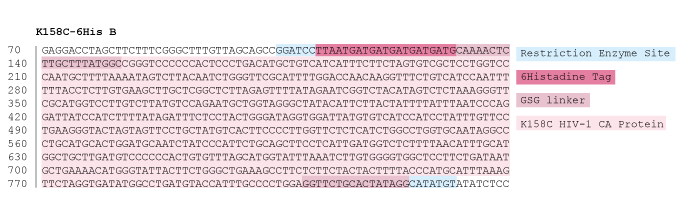

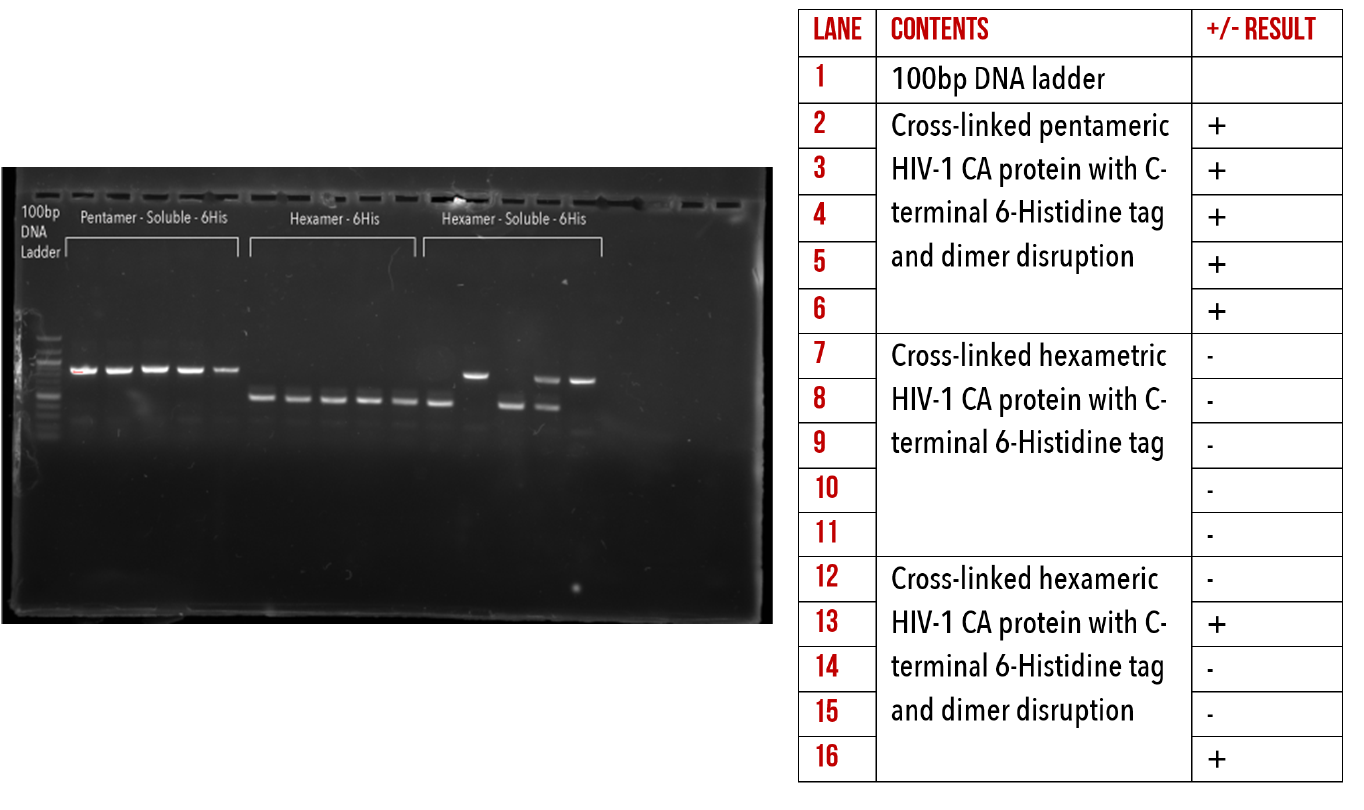

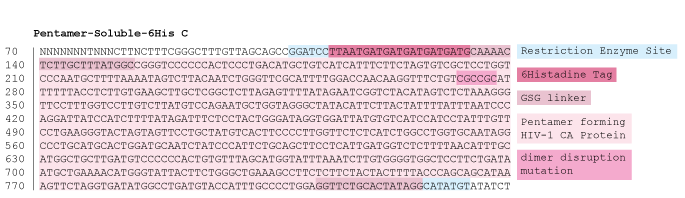

Method 1: Restriction-ligation cloning

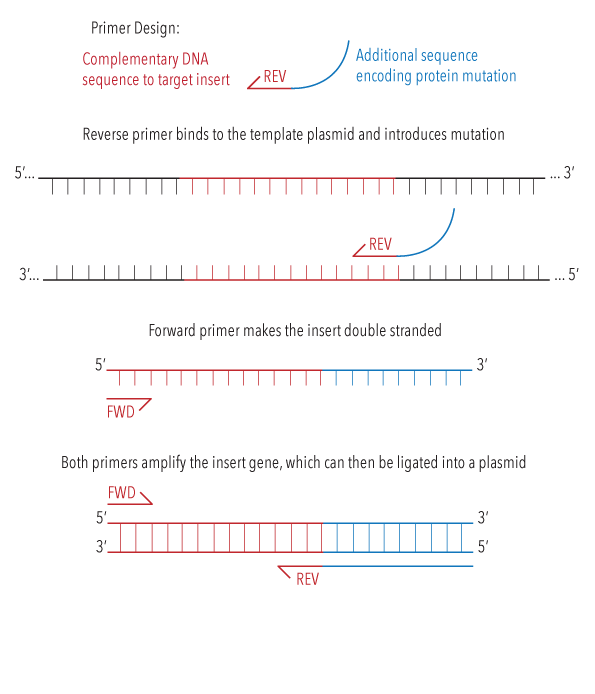

In order to add a polyhistidine tag to the C-terminus of each of our base constructs. The 6-Histidine tag added would enable the protein to form reversible bonds with our DNA templates through Nickel-NTA conjugation chemistry, for use in our kinetic experiments.3 Our protocol for restriction-ligation cloning was adapted from Addgene.5 We designed reverse primers with this encoded mutation, DNA sequences of which can be found here. We then used these primers in a PCR amplification of our base constructs, and in doing so our mutations were added to the C-terminal ends of the proteins.

Figure 2: Diagram illustrating the process of sequence insertion through PCR amplification

These PCR amplified inserts, which now contained additional C-terminal base pairs, were visualised using gel electrophoresis, to check they were the correct size, the yields, and the purity. As we can see in Figure 3, our constructs ran at the expected height on the gel, so we proceeded to insert the amplified genes into our plasmid vector.

Figure 3: 1% agarose gel verifying successful amplification of HIV-1 CA proteins with C-terminal 6-Histidin additions

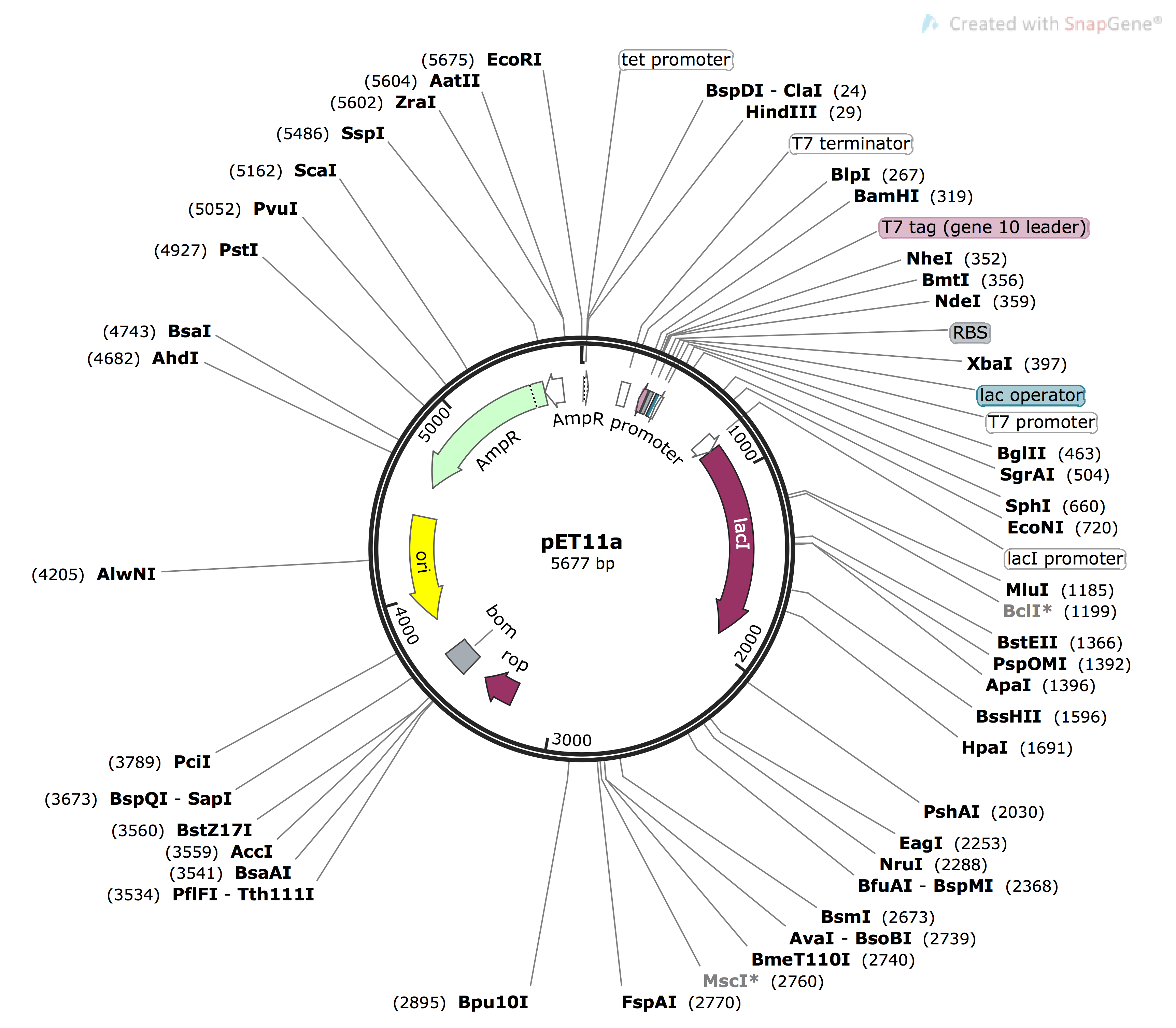

The next step for creating functional plasmids to be used in protein expression was insertion of our new, mutated gene into our vector, pET11a (Figure 4).6 This plasmid confers an ampicillin resistance gene (see the green arrow from base pairs 4609 to 5469, ‘AmpR’), which enables us to select for bacteria which have taken up this target plasmid during plasmid amplification and sequence verification. Our target cloning sites are located at restriction enzyme sites BamHI (319) and NdeI (359). Expression is under the control of the Lac operon (purple arrow), inducible by IPTG

Figure 4: Plasmid Map of pET11a vector, sequence obtained from Addgene1, image generated using snapgene.

We restriction digested both the gene inserts and vectors plasmids with BamHI and Ndel. This resulted in the creation of complementary ‘sticky ends’, which allow for the insert to be slotted into the plasmid. Enzymes were removed after the reaction using PCR clean up (Promega kit7). The inserts were then ligated into the plasmids, ready for amplification and subsequent sequence analysis.

Method 2: Site directed mutagenesis

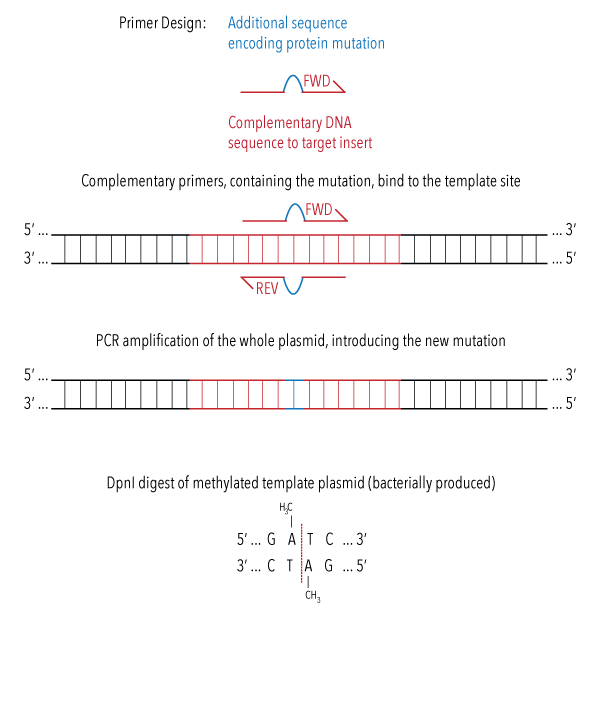

In order to make single nucleotide changes within our base constructs, we attempted site directed mutagenesis. Our protocol was adapted from methods proposed by Agilent Genomics.8 We designed primers with additional nucleotides between complementary DNA to our target gene. Sequences for these primers can be found here. PCR amplification of the entire plasmid was then performed using these primers, which results in the insertion of the new nucleotides into the gene of interest.

Figure 5: diagram illustrating the process of site directed mutagenesis during PCR amplification of whole plasmid.

The PCR reaction mixture was treated with DpnI restriction enzyme, which would break down plasmids which do not contain any mutation. These plasmids are identified as they are bacterially produced, causing methylation. Enzymes were removed after the reaction using PCR clean up kit.

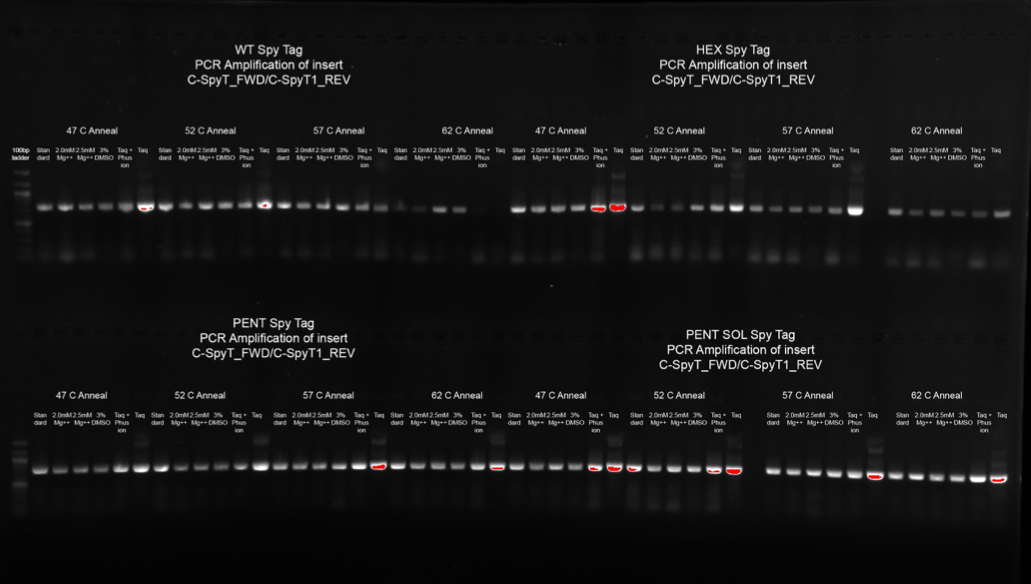

Insertion of our desired mutations into the plasmid were confirmed using gel electrophoresis (Figure 6). We performed a PCR optimisation, to ascertain the best conditions for performing site directed mutagenesis. Annealing temperatures for primer bindings were tested at 47oC, 52oC, 57 oC, and 62 oC. Additions of Magnesium, DMSO, and different polymerase enzymes were also screened. The brightest bands correlate to the highest yields of amplified plasmid. Figure 6 shows that our mutation was successfully introduced into the plasmid under all conditions, with the optimal condition across constructs a 57oC anneal using Taq polymerase enzyme.

Figure 6: 1% agarose gel confirming addition of Spy Tag peptide sequence to the C-terminus of HIV-1 CA base plasmid constructs, using site directed mutagenesis.

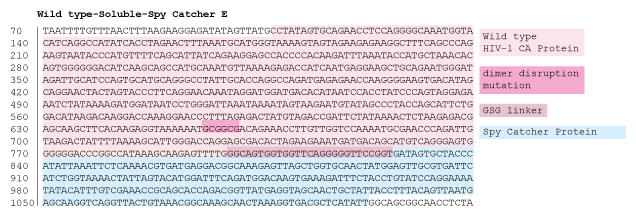

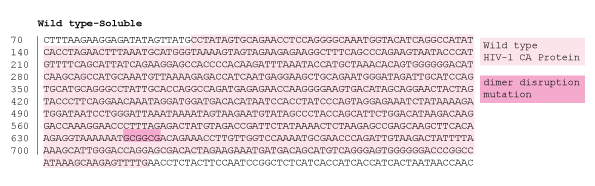

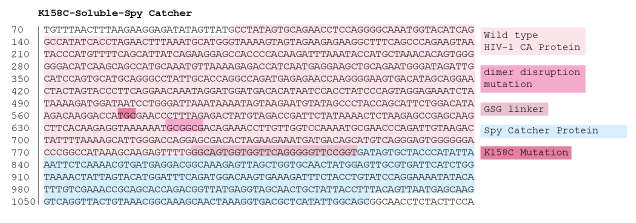

Method 3: Gibson assembly

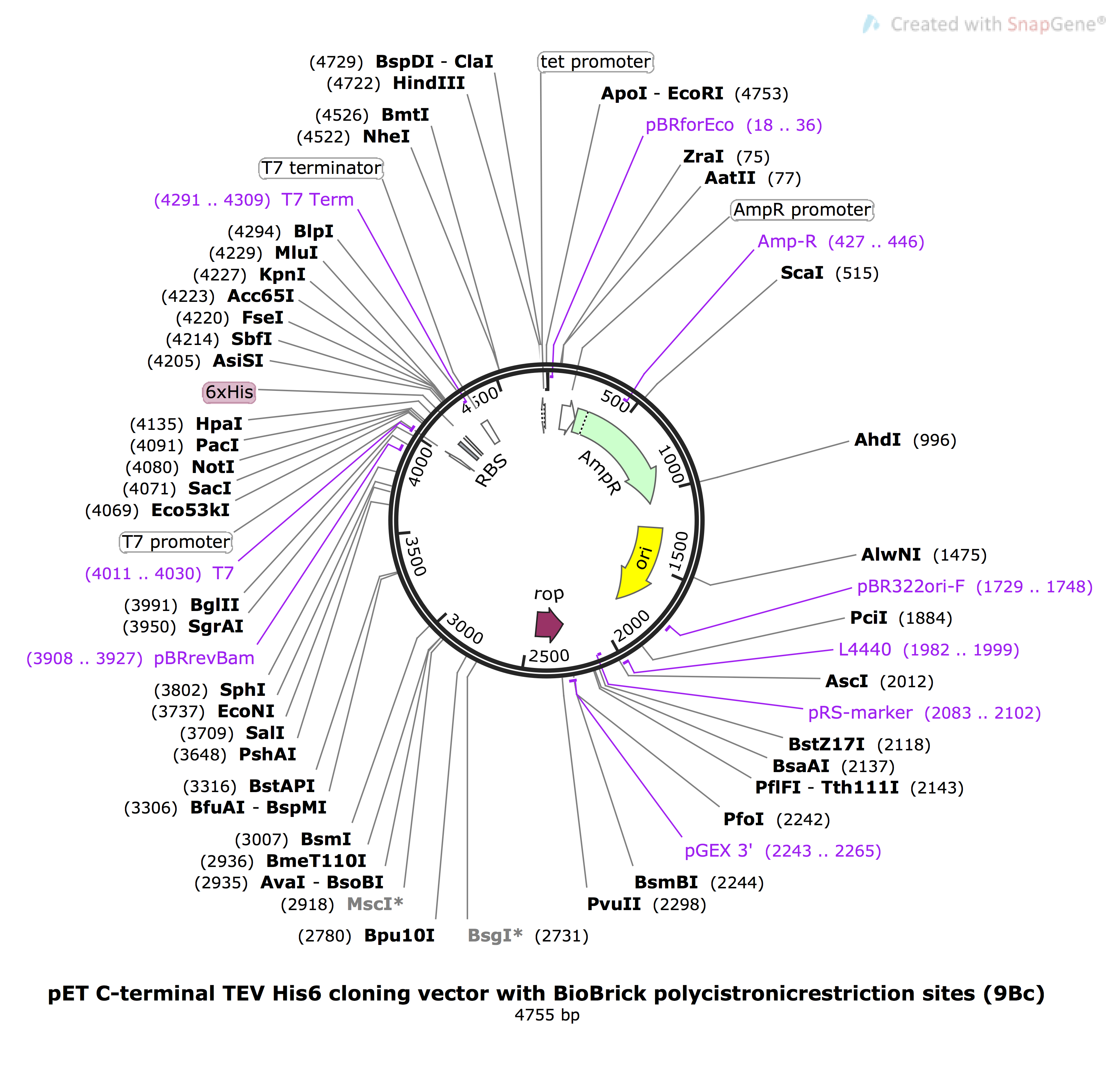

In order to introduce larger mutations to our plasmid constructs, such as Spy Catcher proteins, we used Gibson Assembly. Addition of a Spy Catcher protein at the C-terminal of our HIV-1 CA proteins would allow for irreversible Spy Catcher/Spy Tag conjugation to our DNA scaffolds.4 Large pieces of DNA sequences, gBlocks, were designed to encode our desired mutations and synthesised by IDT. These were inserted into a pET C-terminal TEV His6 cloning vector with BioBrick polycistronic restriction sites (9bc), a gift from Scott Gradia (Addgene plasmid #48285).9 This plasmid, as visualised in Figure 7, was chosen as it contains a gene for amplicilin resistance, labelled green ‘AmpR’ on the plasmid map below, to allow for screening of successful transforms during plasmid amplification. The cloning site is found at restriction enzyme site HpaI (4135). The Lac operon found on a plasmid within our expression strain of E. coli is able to be induced by IPTG. This operon controls the expression of a T7 polymerase gene, which consequently binds to the T7 promoter site on pET9bc (4011), inducing expression of the insert at HpaI cloning site.

Figure 7: Plasmid map of pET9bc, sequence obtained from Addgene,8 image generated used Snapgene.

Assembly of our recombinant plasmid was performed using the Gibson method,10 as outlined in Figure 8. Our plasmid was linearised with Hpa1 restriction enzyme, then combined with our gBlocks and Gibson Assembly Master Mix. This was incubated for 30 minutes at 50oC. Generated plasmids were directly used for transformations into E. coli.

Figure 8: Diagram illustrating the process of Gibson assembly sequence insertion into pET9bc plasmid

Plasmid amplification and sequence verification

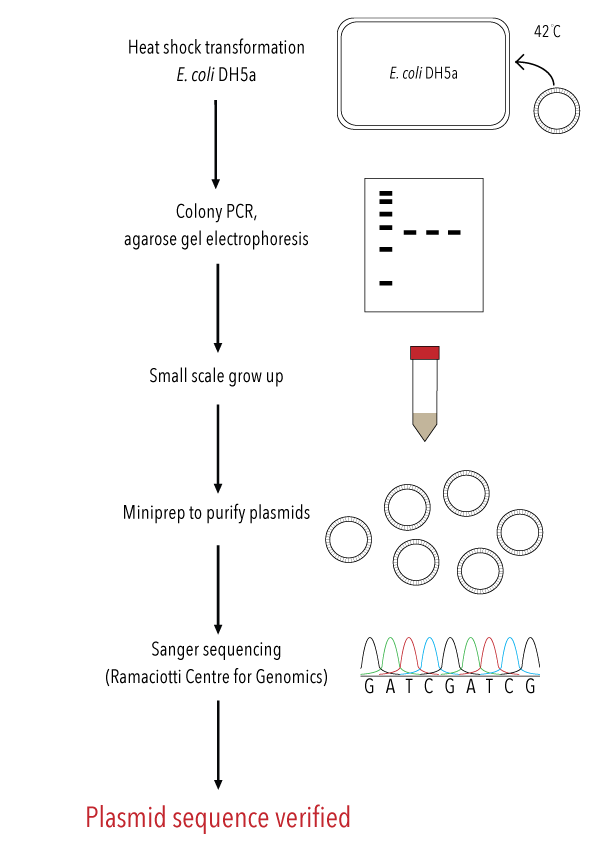

After producing our recombinant plasmids, the next step was to transform these into our competent cells for plasmid amplification. We heat shock transformed our plasmids into a strain of E. coli optimised for cloning, DH5-alpha. This strain was chosen because it undergoes large-scale plasmid production, which we can then harvest for sequencing. After heat shock, our E. coli were plated onto LB agar containing ampicillin antibiotic.

Due to the antibiotic resistance gene within our plasmid, only bacteria which had been successfully transformed should have grown on our plates. Colonies were selected from the plates, and a colony PCR performed to confirm successful transformation of our recombinant plasmids. Those colonies with the correct plasmids were grown up, and then a miniprep performed to extract and purify the plasmids. As a final confirmation of successful plasmid production with the correct mutation, Sanger sequencing was performed by the Ramaciotti Centre for Genomics to verify gene sequences. An overview of this process is demonstrated in Figure 9.

Figure 9: Overview of transformation and colony PCR to verify insertion, followed by plasmid harvesting and sequence verification to generate sequence level confirmation of mutation to our target gene.

RESULTS

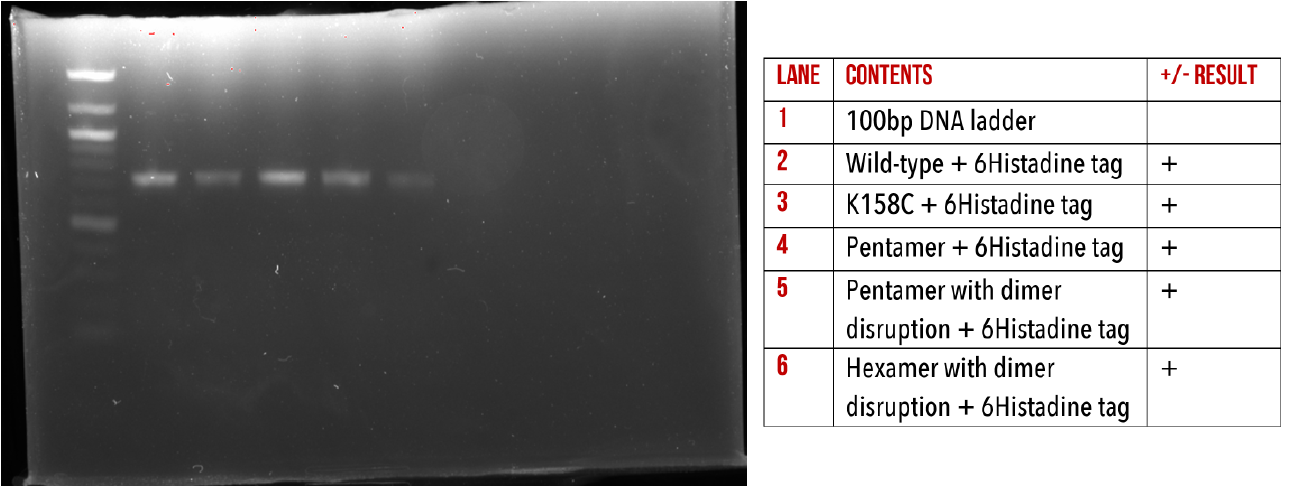

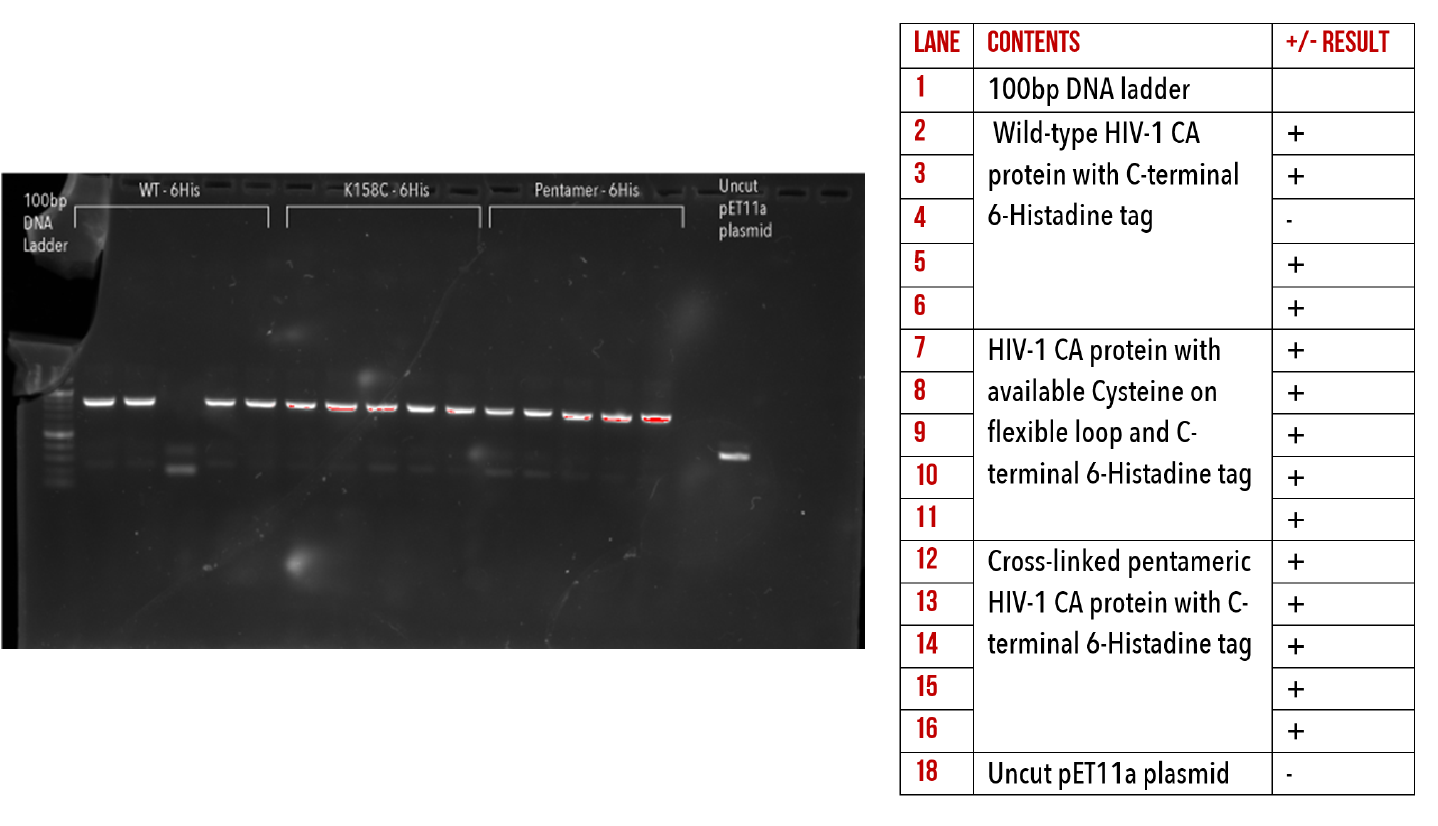

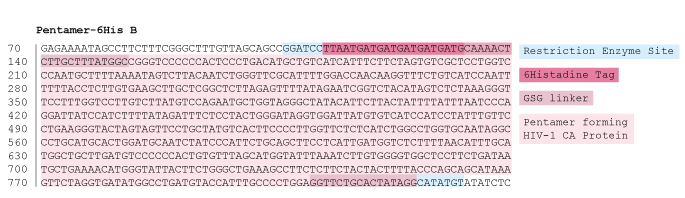

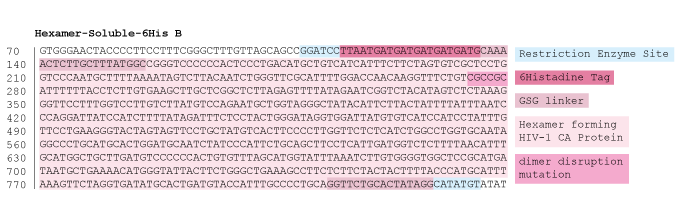

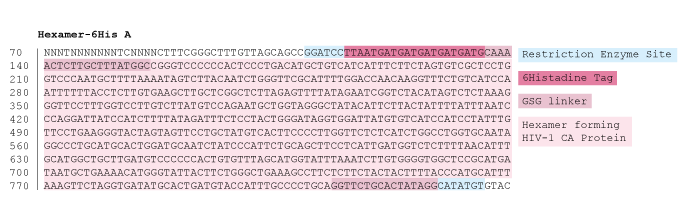

Restriction-Ligation cloning

We have successfully introduced 6-Histidine tags to the C-terminus all of our base constructs via restriction-ligation cloning. This has enabled us to produce HIV-1 CA proteins which can be conjugated to our DNA origami using Nickel/NTA chemistry. The presence of our target inserts was confirmed by performing colony PCR (Figures 10, 11 and 12), to amplify the gene of interest from whole colonies. This produced an amplified band of DNA, with a size corresponding to our target gene, verified by comparison to the ladder. This was repeated on several colonies per construct.

Figure 10: 1% agarose gel of Colony PCR on C-terminal 6-Histidine mutants.

Figure 11: 1% agarose gel of Colony PCR on C-terminal 6-Histidine mutants.

Figure 12:1% agarose gel of Colony PCR on Hexameric HIV-1 CA protein constructs with C-terminal 6-Histidine.

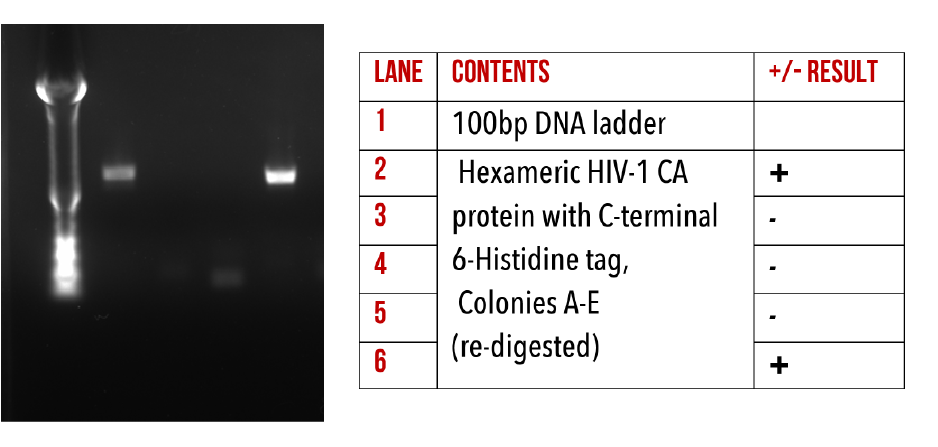

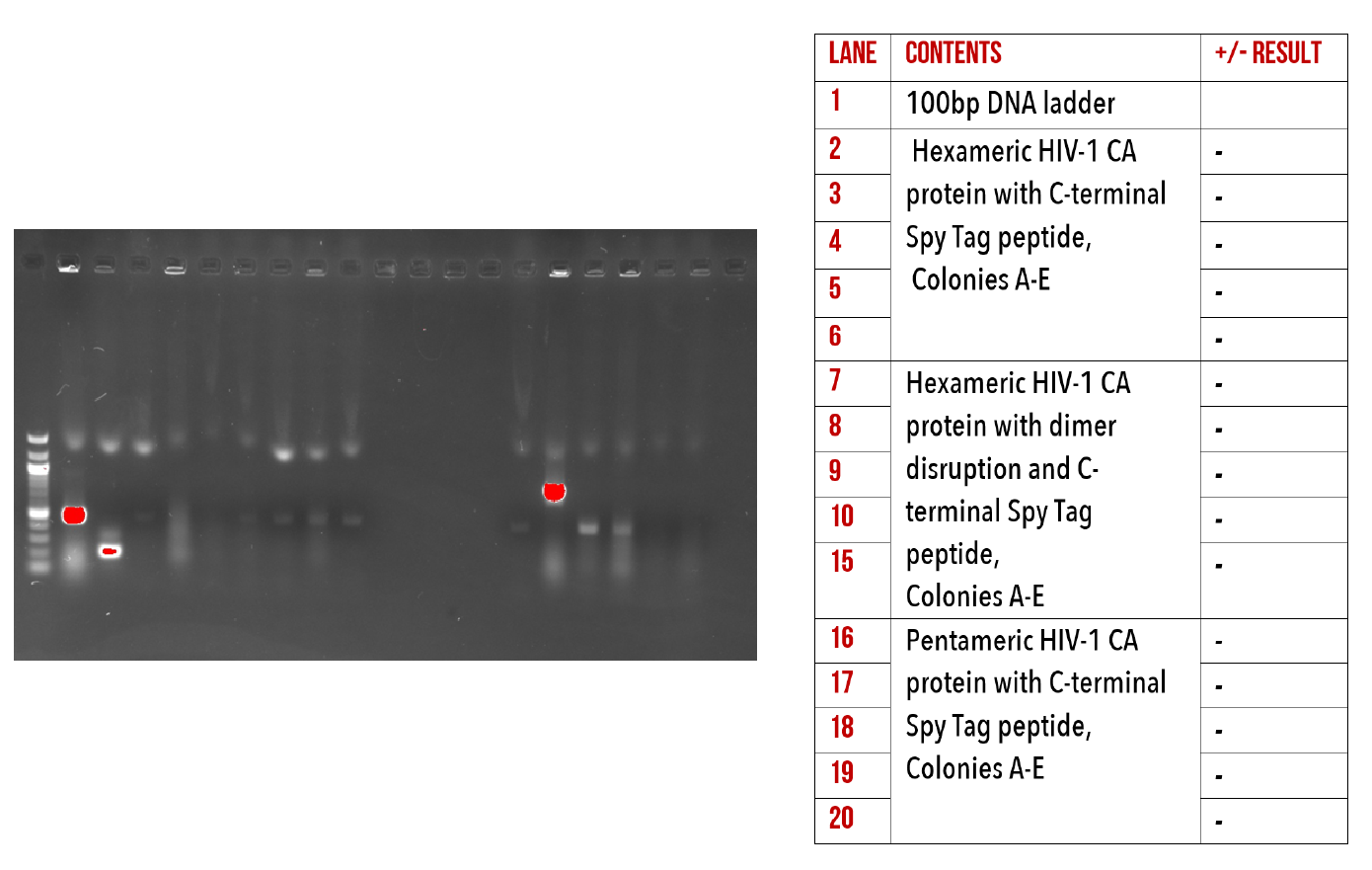

Site Directed Mutagenesis

Although we were able to produce correctly sized constructs during PCR amplification, we were unable to successfully transform these vectors into our expression strain, as shown in our unsuccessful colony PCRs below (Figure 13). We believe that our issues with this cloning technique may have been due to issues in either digestion or transformation of the plasmids. For more information on this process please refer to our supplementary materials. In the interest of time, we decided to focus our efforts towards Gibson Assembly as an alternate method of introducing our mutations.

Figure 13: 1% agarose gel of Colony PCR on C-terminal Spy Tag mutants.

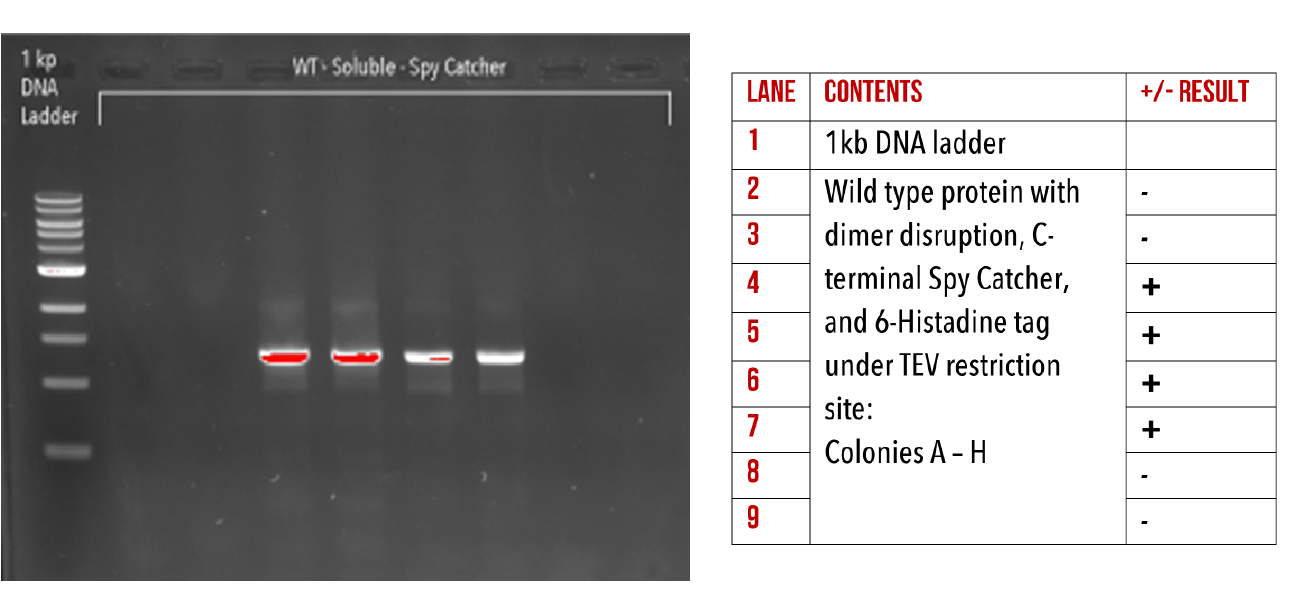

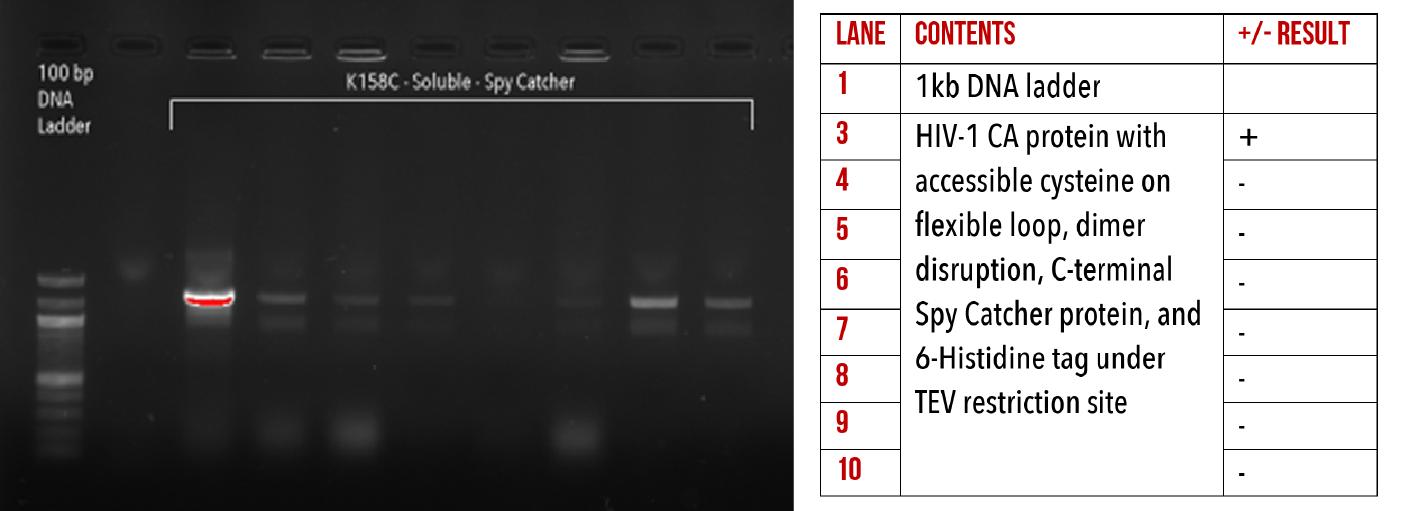

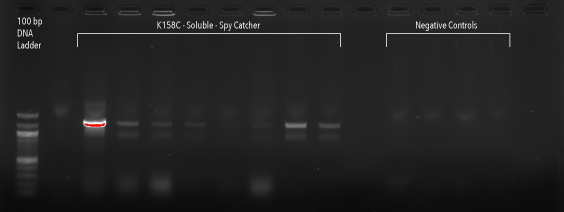

Gibson Assembly

We were also successful in creating a number of important recombinant plasmids using the Gibson Assembly method. Due to the time restraints of the competition, we decided to focus on a select number of mutated proteins which would be most useful for our analysis experiments. See below our colony PCR gels confirming insertion of our gBlocks into our plasmids (Figures 14, 15, and 16).

Figure 14: 1% agarose gel of Colony PCR on Gibson assembly of Wild-Type HIV-1 CA with dimer disruption and C-terminal Spy Catcher protein.

Figure 15: 1% agarose gel of Colony PCR on Gibson Assemblies of Wild type protein with dimer disruption and C-terminal 6-Histidine tag, and HIV-1 CA protein with accessible cysteine on flexible loop, dimer disruption and C-terminal 6-Histidine tag.

Figure 16: 1% agarose gel of Colony PCR on Gibson Assembly of HIV-1 CA protein with accessible cysteine on flexible loop, dimer distruption, C-terminal Spy Catcher protein, and 6-Histidine tag

Discussion

Of the 36 possible plasmids containing mutated HIV-1 CA protein sequences we could potentially have generated, 16 were produced and positive sequencing results confirmed. Ideally, all constructs would have been made to allow for a number of different aspects of capsid assembly to be tested, but due to the time restraints of the competition this was no feasible. We were, however, successful in producing the most important constructs for preliminary kinetic and structural analysis. Below is a list of all our successful plasmid constructs, with their associated potential experimental uses.

Base Constructs

- Wild type HIV capsid protein (HIV-1 CA wild type) - Positive control for analysis experiments

- Disulfide bond stabilised hexamer (HIV-1 CA A14C/E45C) - Used for testing lattice assembly and analysing hexamer-hexamer interaction

- Disulfide bond stabilised hexamer with C-terminal dimer disruption (HIV-1 CA A14C/E45C/W184A/M185A) - Used for testing hexameric affinity to DNA

- Disulfide bond stabilised pentamer (HIV-1 CA N21C/A22C) - Used For testing lattice assembly and analysing pentamer-hexamer interaction

- Disulfide bond stabilised pentamer with C-terminal dimer disruption (HIV-1 CA N21C/A22C/W184A/M185A) - Used for testing pentameric affinity to DNA

- Accessible cysteine on the N-terminus flexible loop (HIV-1 CA K158C) - Accessible cysteine for conjugation to fluorophores, for use in single molecule imaging experiments

C-Terminal mutations

- HIV-1 CA Wild-type protein with C-terminal 6-Histidine tag

- HIV-1 CA protein with K158C substitution and C-terminal 6-Histidine tag

- HIV-1 CA cross-linked hexameric protein with C-terminal 6-Histidine tag

- HIV-1 CA HIV-1 CA cross-linked hexameric protein with dimer disruption and C-terminal 6-Histidine tag

- HIV-1 CA cross-linked pentameric protein with C-terminal 6-Histidine tag

- HIV-1 CA HIV-1 CA cross-linked pentameric protein with dimer disruption and C-terminal 6-Histidine tag

Addition of a 6-Histidine tag will allow for each protein to be reversibly conjugated to our DNA scaffolds.

Gibson Assemblies

- HIV-1 CA Wild-type protein with dimer disruption and 6-Histidine tag under TEV restriction site - Used to test intra-hexamer or intra-pentamer interactions, with reversible conjugation chemistry to DNA

- HIV-1 CA Wild-type protein with dimer disruption, C-terminal Spy Catcher protein, and 6-Histidine tag under TEV restriction site - Used to test intra-hexamer or intra-pentamer interactions, with reversible and irreversible conjugation chemistry to DNA

- HIV-1 CA protein with K158C substitution, dimer disruption, and 6-Histidine tag under TEV restriction site - Used to test intra-hexamer or intra-pentamer interactions during single molecule experiments, with reversible conjugation chemistry to DNA

- HIV-1 CA protein with K158C substitution, dimer disruption, C-terminal Spy Catcher protein, and 6-Histidine tag under TEV restriction site - Used to test intra-hexamer or intra-pentamer interactions during single molecule experiments, with reversible and irreversible conjugation chemistry to DNA

With our desired mutations now successfully cloned into plasmids, our constructs were ready for expression. Click here to read about how we expressed our proteins!

References

- Pornillos, O., Ganser-Pornillos, B., Kelly, B., Hua, Y., Whitby, F., Stout, C., Sundquist, W., Hill, C. and Yeager, M. (2009). X-Ray Structures of the Hexameric Building Block of the HIV Capsid. Cell, 137(7), pp.1282-1292.

- Jacques, D., McEwan, W., Hilditch, L., Price, A., Towers, G. and James, L. (2016). HIV-1 uses dynamic capsid pores to import nucleotides and fuel encapsidated DNA synthesis. Nature, 536(7616), pp.349-353.

- Hochuli, E., Bannwarth, W., Döbeli, H., Gentz, R. and Stüber, D. (1988). Genetic Approach to Facilitate Purification of Recombinant Proteins with a Novel Metal Chelate Adsorbent. Nature Biotechnology, 6(11), pp.1321-1325.

- Li, L., Fierer, J., Rapoport, T. and Howarth, M. (2014). Structural Analysis and Optimization of the Covalent Association between SpyCatcher and a Peptide Tag. J Mol Biol, 426(2), pp.309-317.

- Addgene, Plasmid Cloning by PCR, https://www.addgene.org/protocols/pcr-cloning/

- Addgene, Vector Database, Plasmid: pET11a, https://www.addgene.org/vector-database/2625/

- Promega, Wizard SV Gel and PCR Clean-Up system, https://www.promega.com.au/resources/protocols/technical-bulletins/101/wizard-sv-gel-and-pcr-cleanup-system-protocol/

- Agilent Genomics, QuikChange II Site-Directed Muagenesis Kit, https://www.agilent.com/cs/library/usermanuals/public/200523.pdf

- Addgene, pET C-terminal TEV His6 cloning vector with BioBrick polycistronic restriction sites (9bc), https://www.addgene.org/48285/

- Gibson DG, Young L, Chuang RY, Venter JC, Hutchison CA 3rd, Smith HO (2009). Enzymatic assembly of DNA molecules up to several hundred kilobases.Nature Methods,6(5), pp. 343–345.