Introduction

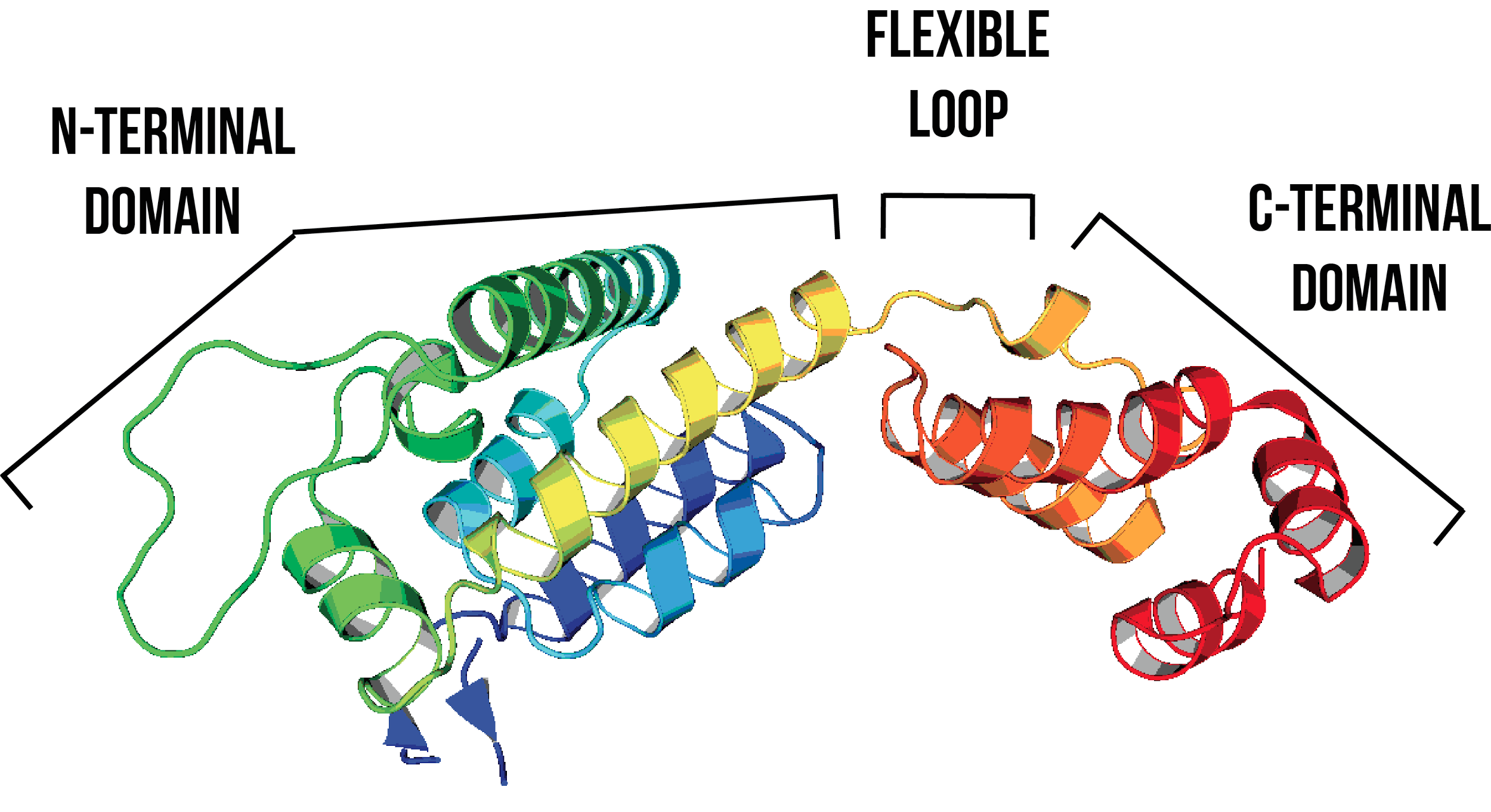

The HIV viral capsid is formed entirely of hexamers and pentamers of the HIV-1 capsid protein (HIV-1 CA). The HIV-1 CA protein has two domains, an N-terminal domain (NTD) and a C-terminal domain (CTD), connected by a flexible linker (Figure 1). Intra-hexamer and intra-pentamer NTD-NTD and NTD-CTD interactions stabilise hexamer and pentamer structures, whereas CTD-CTD interactions stabilise the lattice structure between adjacent hexamers or pentamers. CTD-CTD interactions also cause the CA protein to form dimers across the hexamer-hexamer or the hexamer-pentamer interface. Despite extensive research, formation of CA hexamer or pentamer structures in vitro in its native form without disulfide bond cross-linking1-3 or protein templating1 has not yet been reported.

Figure 1: The HIV-1 CA protein consists of an NTD (residues 1-145) and a CTD (residues 150-231), connected by a flexible loop (residues 146-149)5,6. Image created using PDB ID: 4XFX7. Helices are coloured systematically from the NTD (blue) to CTD (red).

Our project aims to template HIV-1 CA proteins onto a DNA origami scaffold, to visualise these structures and to investigate the kinetics of capsid formation. In order to ascertain the kinetics of HIV capsid assembly, individual binding events between proteins needed to be isolated and measured. We have designed a number of mutations to the wild-type HIV-1 capsid protein, which will allow us to better observe specific interactions of interest, and develop a model of self-assembly from fundamental kinetic principles.

Aims

To design mutations in HIV-1 CA protein that will enable the protein to:

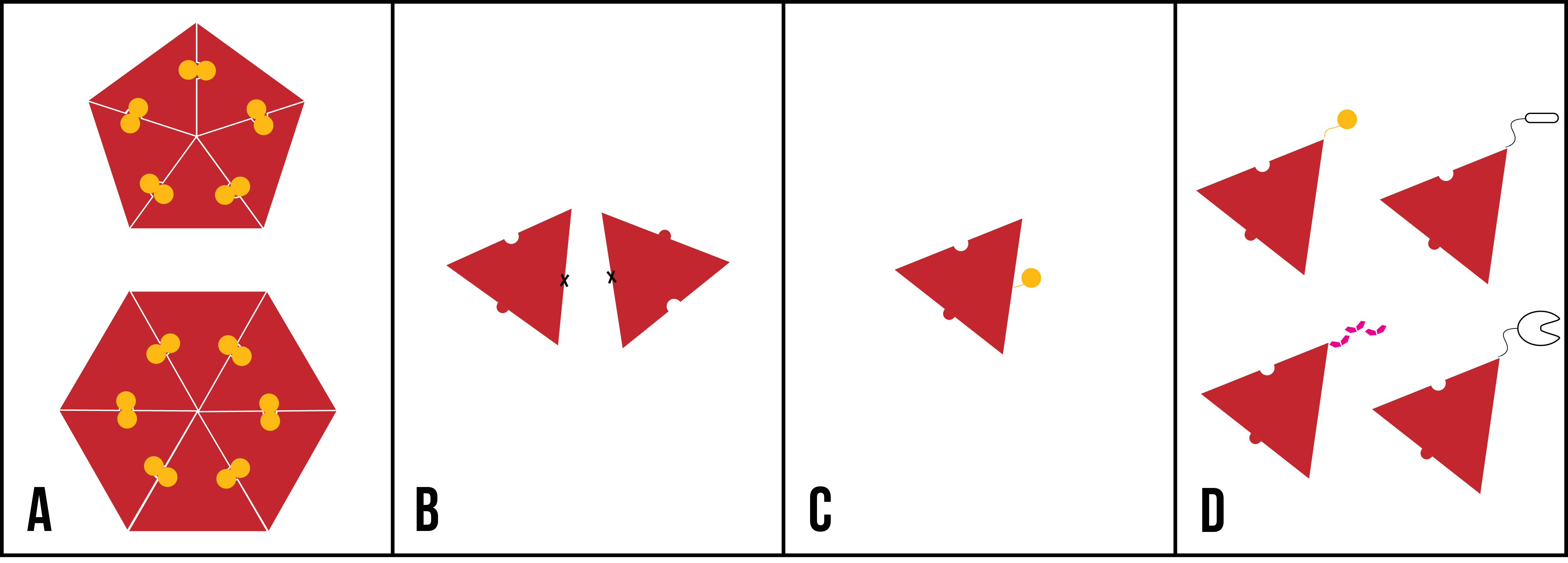

- have disulfide bond cross-links to spontaneously form discrete and stable hexameric and pentameric structures (Figure 2A);

- avoid dimerisation between CA proteins from adjacent hexamers, to probe intra- hexamer and pentamer interactions (Figure 2B);

- contain sites for irreversible conjugation to fluorophores, for visualisation with single molecule fluorescence (Figure 2C);

- contain sites for reversible and irreversible conjugation to DNA (Figure 2D).

Figure 2: Cartoon representations of desired mutations to introduce to HIV-1 CA protein, represented as a red triangle. (A) Cross-linked CA pentamer and hexamer mutants; (B) dimer-disrupting CA mutants; (C) CA with an available cysteine residue (represented as a yellow circle); (D) CA with reversible and irreversible conjugation mechanisms (clockwise from top left: cysteine residue, SpyTag [black oval], SpyCatcher [black ‘C’ shape], polyhistidine tag [six pink polygons]).

Naming conventions

For ease of reading, we have established the following naming conventions for HIV-1 CA protein mutants, utilised throughout this website. CA hexamers stabilised by the disulfide bond A14C/E45C are referred to as ‘cross-linked hexamer’, and CA pentamers stabilised by the disulfide bond N21C/A22C are referred to as ‘cross-linked pentamer’. Any CA mutant containing W184A/M185A substitutions are labelled ‘discrete’ (if additionally containing cross-linking mutations) or ‘monomeric’ (not cross-linked). A C-terminal polyhistidine tag is referred to as ‘6His’.

Mutations

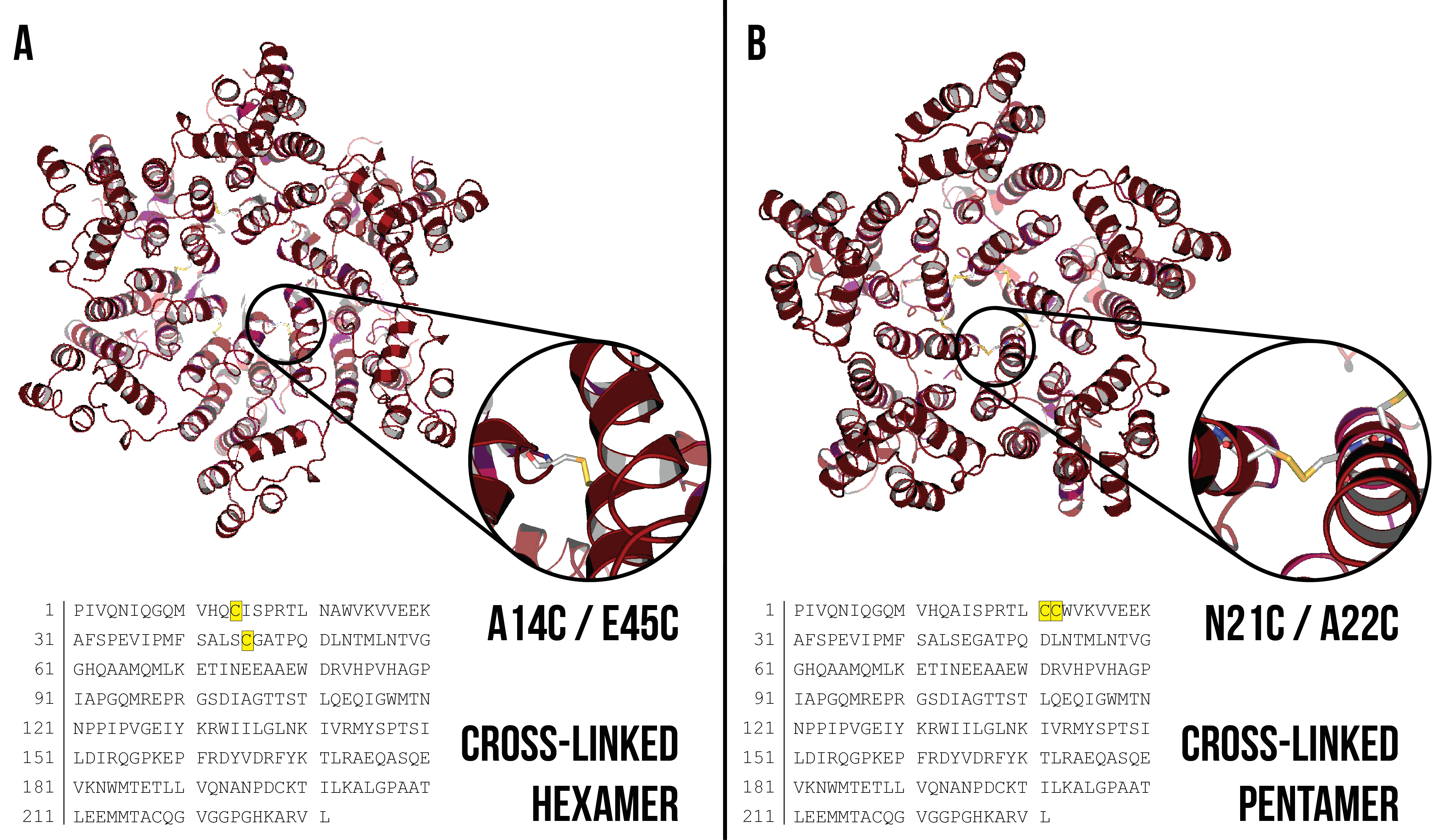

Disulfide bond cross linking

A14C/E45C – cross-linked hexamer

N21C/A22C – cross-linked pentamer

Cysteine residues have an available sulfhydryl group (-SH) that can form covalent bonds with another sulfhydryl group upon oxidation. Disulfide bonds between two cysteine residues can help stabilise tertiary and quaternary protein structure. Disulfide bond stabilised CA protein hexamer structures were first reported by Pornillos et al. 20091 by introducing cysteine residues at the positions A14 and E45, and have been well characterised by X-ray diffraction1,3 (Figure 3a). Disulfide bond stabilised CA protein pentamer structures were also reported by Pornillos et al. 20112 (Figure 3b) through a similar method. Cross-linking was introduced to induce a pentameric structure by mutating residues N21 and A22 to cysteine residues.

Figure 3: (A) Disulfide bond cross-linked CA hexamer with A14C/E45C mutation highlighted. Cysteine residues are shown inset. Image created using PDB ID: 3H471. (B) Disulfide bond cross-linked CA pentamer with N21C/A22C mutation highlighted. Cysteine residues are shown inset. Image created using PDB ID: 3P052.

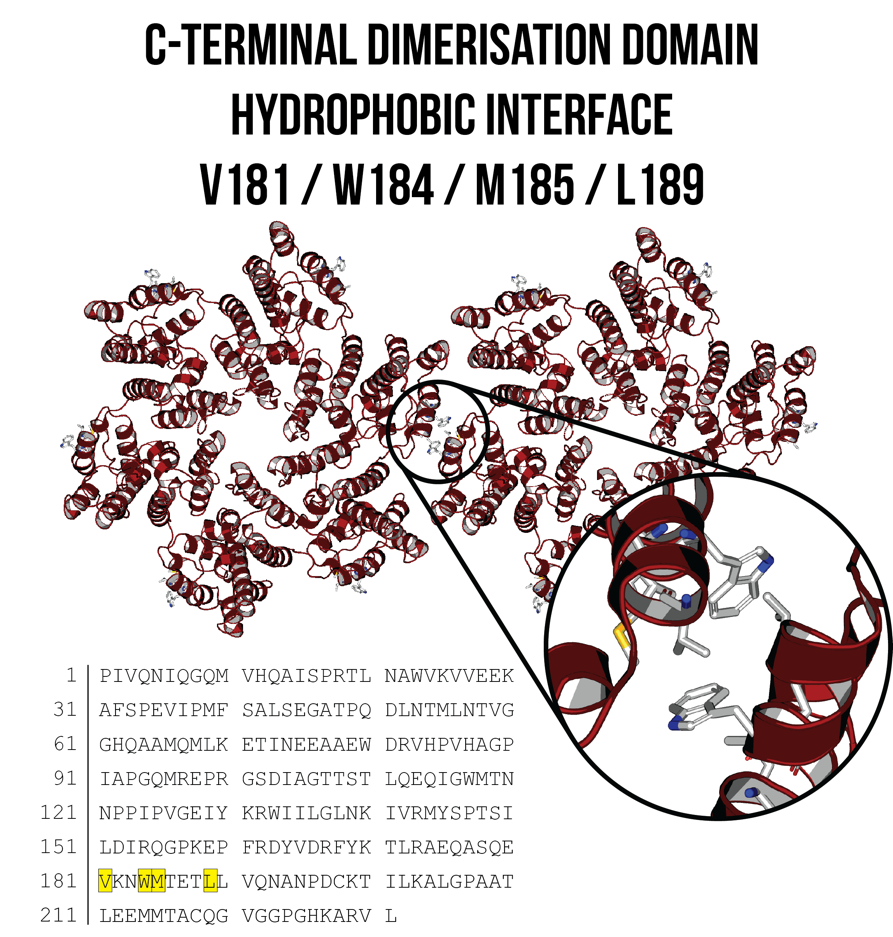

Disruption of dimerisation between CA proteins from adjacent hexamers

W184A/M185A – discrete/monomeric mutation

Gamble et al. (1997) introduced alanine residues at position W184 and M185 to disrupt hydrophobic C-terminal dimerisation interactions that occur between adjacent hexamers (Figure 4). These mutations have been used in addition to disulfide bond cross-linking to produce discrete hexamer and pentamer structures that do not polymerise and are less prone to aggregation1-4. The W184A/M185A mutations are especially important for kinetic experiments, as it ensures that we are measuring protein binding events between monomers that are of the same hexamer or pentamer, and not between monomers from adjacent hexamers or pentamers.

Figure 4: C-terminal dimerisation domain between two adjacent CA hexamers, with the hydrophobic interface shown inset. W184A/M185A substitutions can reduce these hydrophobic interactions and enable the formation of discrete hexamer and pentamer structures. Image created using PDB ID: 4XFX7.

Reversible and irreversible conjugation

(For more information on conjugation, click here)

The templating of CA proteins onto a DNA scaffold requires an attachment mechanism. Three mechanisms have been designed that enable specific reversible and covalent bonding to a DNA scaffold. Covalent bonds enable spontaneous irreversible attachment of CA protein to DNA. Kinetic and imaging experiments require proteins with both types of conjugation.

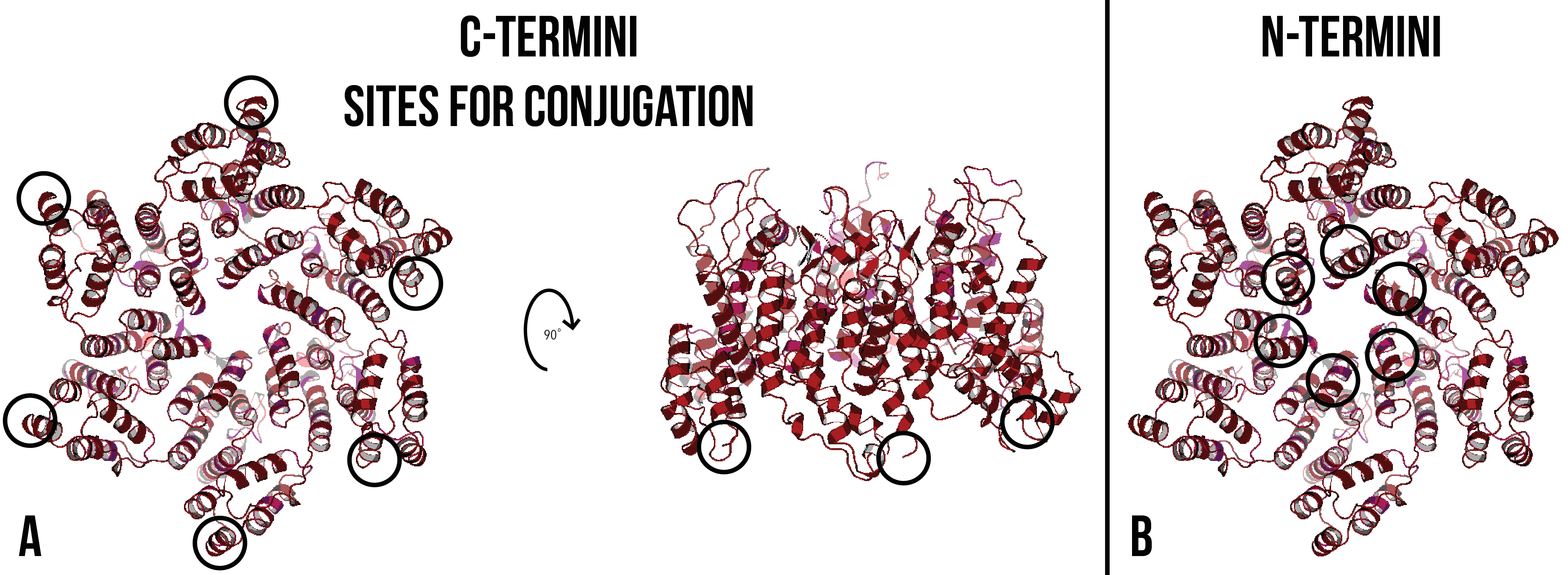

The C-terminus was chosen as the site of conjugation, as crystal structures of the CA hexamer and pentamer show that the N-terminus of the monomers is at the centre of the hexamer and pentamer structures (Figure 5). The introduction of bulky residues may inhibit the formation of hexamers or pentamers by steric hindrance.

Figure 5: (A) CA hexamer with C-termini circled in black. After 90 degrees forward rotation, only three of the C-termini are visible. (B) CA hexamer with N-termini circled in black. Images created using PDB ID: 4XFX7.

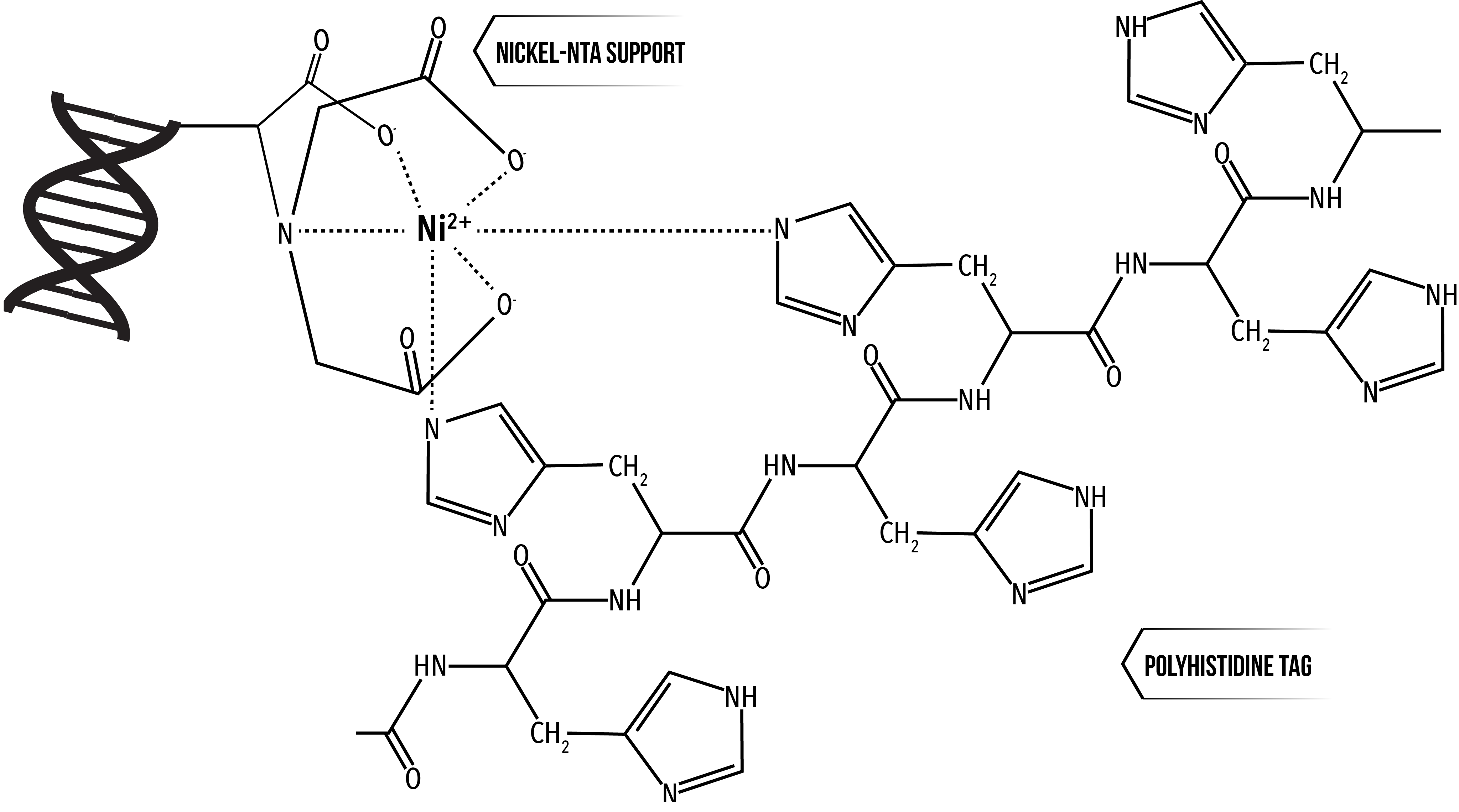

Reversible Conjugation: Polyhistidine tag

Polyhistidine tags are a commonly used amino acid motif for protein purification. Six histidine residues in series (His-tag), usually at the N- or C- terminal of the protein, have affinity to cations, such as nickel ions8. The introduction of a His-tag to the CA protein is useful for both protein purification and attachment to DNA that has been modified with tris-nitrotriloacetic acid (NTA) to chelate three Ni2+ ions. Six histidine residues were therefore introduced at the C-terminus of the CA protein after L231 to facilitate a specific interaction with modified DNA (Figure 6).

Figure 6: 2 histidine residues of a polyhistidine tag coordinating around a nickel ion chelated by nitrotriloacetic acid (NTA) 9. We have modified DNA with 3 NTA groups, which chelate 3 Ni2+ ions, which 6 histidine residues can coordinate around.

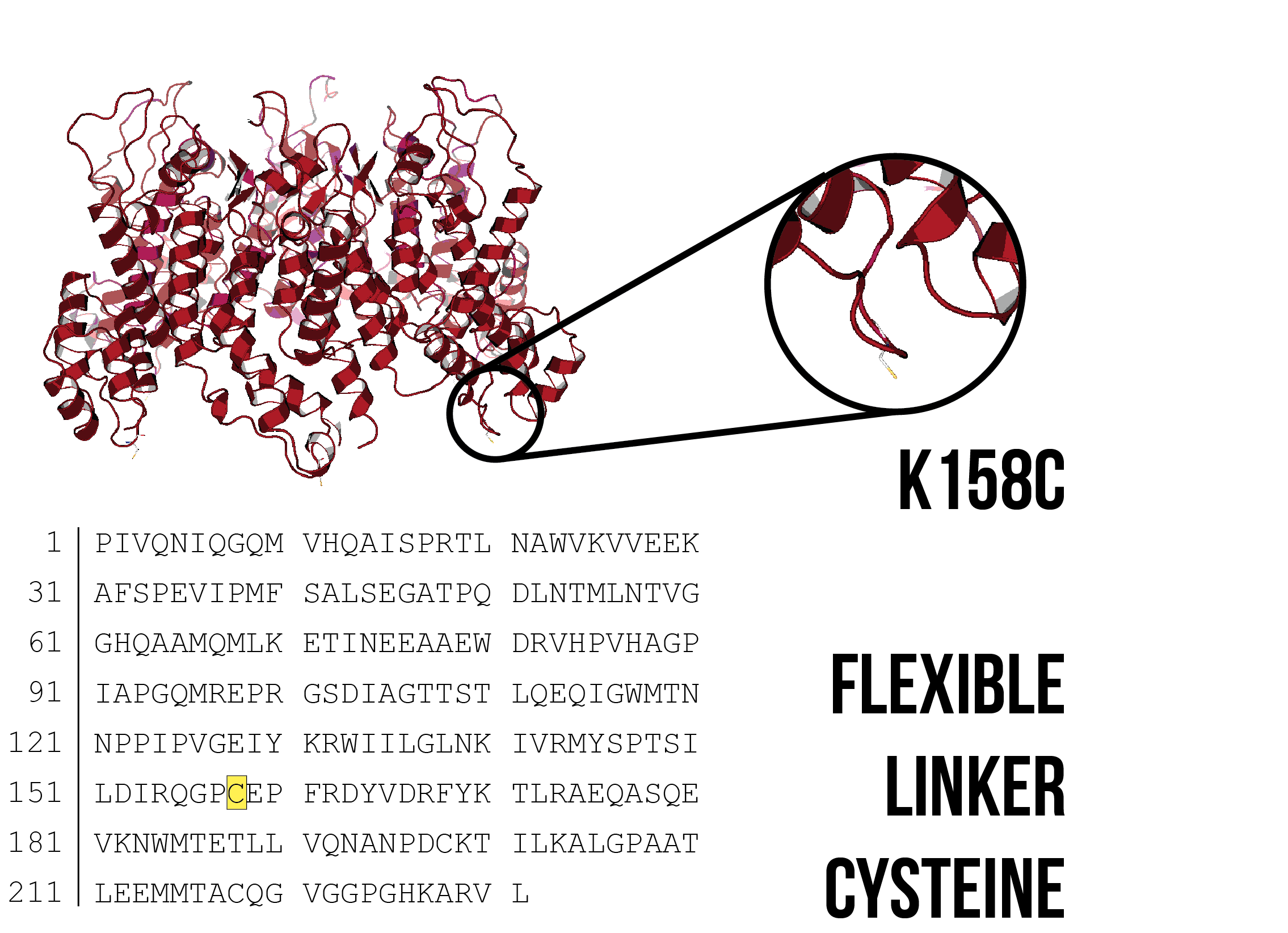

Irreversible conjugation: C-terminal Cysteine and K158C

In addition to covalent bonding to other cysteine residues, the sulfhydryl group of a cysteine residue can covalently bond to compounds containing maleimide groups. These can be used as a conjugation method to link DNA or fluorophores to CA proteins with available cysteine residues. Cysteine residues were introduced at two sites - at the C-terminus after L231, and by mutating K158 to cysteine. Although K158 is not at the C-terminus, it is located on a flexible linker between helices 6 and 7, proximally close to the C-terminus and is accessible for conjugation to DNA (Figure 8).

Figure 7: Model of a CA hexamer with K158C substitution. Image created using PDB ID: 4XFX 7, with PYMOL mutagenesis tool to introduce a cysteine residue at K158.

Irreversible conjugation: SpyCatcher and SpyTag

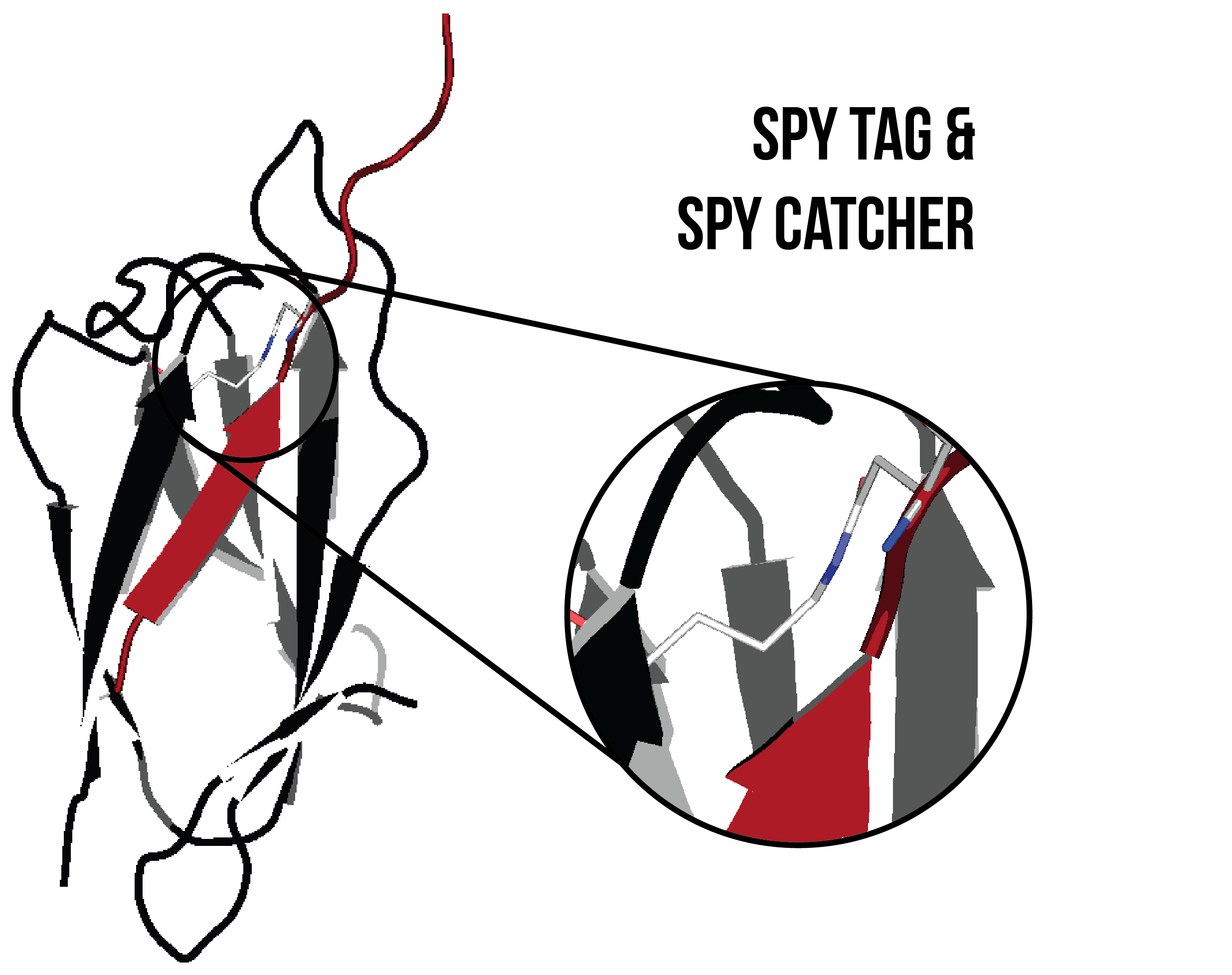

The SpyTag peptide and SpyCatcher protein are isolated fragments of a pilin subunit protein, fibronectin-binding protein FbaB, from Streptococcus pyogenes9,10. A covalent isopeptide bond spontaneously forms between D7 of the SpyTag and K31 of the SpyCatcher (Figure 9). A recombinant HIV-1 CA/SpyTag or HIV-1 CA/SpyCatcher protein would be able to conjugate to a SpyCatcher protein or SpyTag peptide affixed to a DNA scaffold. The SpyTag peptide and the SpyCatcher protein were introduced at the C-terminus after L231, with the SpyCatcher protein preceded by a GSG x 3 linker (Gly-Ser-Gly-Gly-Ser-Gly-Gly-Ser-Gly). A GSG x 3 linker provides flexibility between the SpyCatcher and CA proteins, enabling the CA protein to freely orient itself once affixed onto the DNA scaffold.

Figure 8. SpyTag (red) and SpyCatcher (black) covalently bonded by an isopeptide bond (shown inset). Image created using PDB ID: 4MLI.10

Conclusions

This broad availability of conjugation mechanisms, and the possibility of using the K158C substitution in addition to a C-terminal conjugation mechanism, provides many methods of attachment for kinetic and imaging experiments. There are up to 60 combinations of the mutations described above, as when selecting a mutant 4 decisions must be made; there are 3 disulfide bond cross-linking, 2 C-terminal dimer disrupting, 2 flexible linker conjugation and 5 C-terminal conjugation choices of mutation. They are summarised in the table below.

|

Disulfide bond cross-linking |

W184A/M185A |

K158C |

C-terminal conjugation method |

|

None |

Yes |

Yes |

None |

|

Hexamer (A14C/E45C) |

No |

No |

Polyhistidine tag |

|

Pentamer (A21C/N22C) |

|

|

Cysteine residue |

|

|

|

|

SpyTag |

|

|

|

|

SpyCatcher |

Certain mutation combinations can be eliminated; disulfide bond cross-linking with K158C and/or a C-terminal cysteine could lead to unexpected cysteine-cysteine bonding and malformation of the CA protein. The elimination of these combinations leaves 36 mutation permutations. 16 of these mutations have been successfully cloned into plasmids, and 9 of these proteins have been successfully produced and purified.

When introducing amino acid substitutions, the large number of potential interactions can make it hard to predict the effect of the mutation on protein structures. It is important to note that there is an inter-monomer disulfide bond between C198 and C218 that is close to K158 (approximately 11Å between C-alphas). The introduction of a cysteine residue at this position is unlikely to cause protein misfolding and malformation, as the sulphur atoms of the possible K158C rotamers are not within the Van der Waals radii of the sulphur atoms of C198 and C218, and protein misfolding would cause steric clashes between other residues.

Another important consideration is the effect of C-terminal additions to the assembly of CA lattice structures. It is possible that these conjugation methods could inhibit hexamer-hexamer and hexamer-pentamer interactions, especially the relatively large SpyCatcher protein.

References

- Pornillos, O., Ganser-Pornillos, B., Kelly, B., Hua, Y., Whitby, F., Stout, C., Sundquist, W., Hill, C. and Yeager, M. (2009). X-Ray Structures of the Hexameric Building Block of the HIV Capsid. Cell, 137(7), pp.1282-1292.

- Pornillos, O., Ganser-Pornillos, B. and Yeager, M. (2011). Atomic-level modelling of the HIV capsid. Nature, 469(7330), pp.424-427.

- Price, A., Jacques, D., McEwan, W., Fletcher, A., Essig, S., Chin, J., Halambage, U., Aiken, C. and James, L. (2014). Host Cofactors and Pharmacologic Ligands Share an Essential Interface in HIV-1 Capsid That Is Lost upon Disassembly. PLoS Pathogens, 10(10), p.e1004459.

- Jacques, D., McEwan, W., Hilditch, L., Price, A., Towers, G. and James, L. (2016). HIV-1 uses dynamic capsid pores to import nucleotides and fuel encapsidated DNA synthesis. Nature, 536(7616), pp.349-353.

- Yeager, D. (2011). Design of in vitro Symmetric Complexes and Analysis by Hybrid Methods Reveal Mechanisms of HIV Capsid Assembly. J Mol Biol, 410(4), pp. 534-552.

- Zhao, G., Perilla, J. R., Yufenyuy, E. L., Meng, X., Chen, B., Ning, J., Ahn, J., Gronenborn, A. M., Schulten, K., Aiken, C., Zhang, P. (2013). Mature HIV-1 capsid structure by cryo-electron microscopy and all-atom molecular dynamics. Nature, 497(7451), pp. 643–646.

- Gres, A., Kirby, K., KewalRamani, V., Tanner, J., Pornillos, O. and Sarafianos, S. (2015). X-ray crystal structures of native HIV-1 capsid protein reveal conformational variability. Science, 349(6243), pp.99-103.

- Hochuli, E., Bannwarth, W., Döbeli, H., Gentz, R. and Stüber, D. (1988). Genetic Approach to Facilitate Purification of Recombinant Proteins with a Novel Metal Chelate Adsorbent. Nature Biotechnology, 6(11), pp.1321-1325.

- Kang, H. J, Coulibaly F., Clow F., Proft T., Baker E. N. (2007). Stabilizing isopeptide bonds revealed in gram-positive bacterial pilus structure. Science. 318, pp.1625–1628.

- Li, L., Fierer, J., Rapoport, T. and Howarth, M. (2014). Structural Analysis and Optimization of the Covalent Association between SpyCatcher and a Peptide Tag. J Mol Biol, 426(2), pp.309-317.