Relevance

Background

Self-assembly is a powerful theme found at all levels of biological life. From the imposing sight of a murmuration of birds, to the incredible way microbes coordinate behaviour to search and obtain nutrients, the principle of spontaneous formation of complex systems from simple subunits is abundant. We are interested in learning more about this fundamental principle of self-assembly.

There has been substantial academic interest in the process of self-assembly. Systems such as the bacterial flagellar motor display finely-tuned properties that facilitate movement of simple organisms, despite being constructed from individual subunits with knowledge only of their immediate neighbour.1 Viral capsids self-assemble from individual proteins, creating a shield that protects the genomic material within.

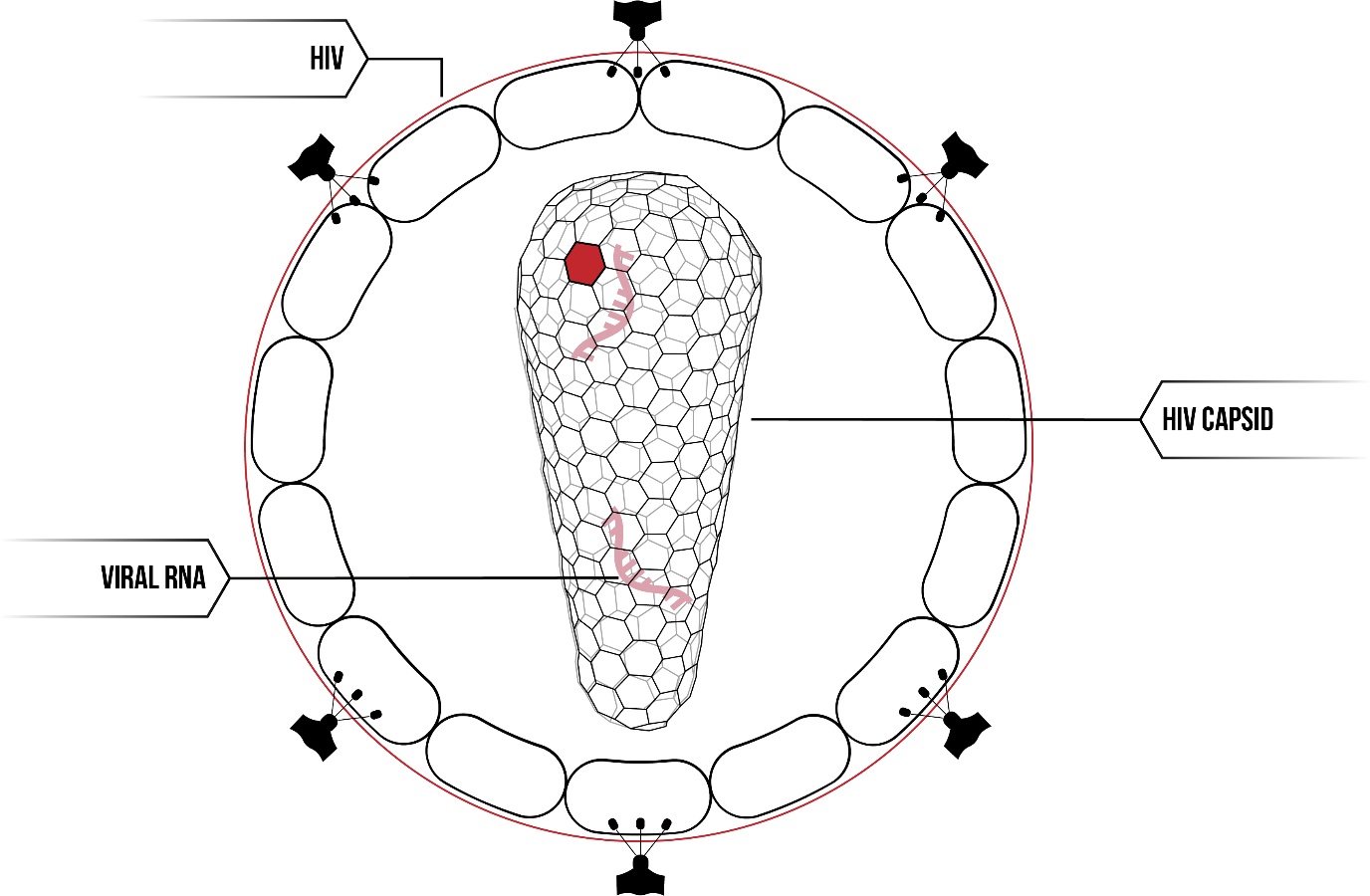

The human immunodeficiency virus (HIV-1) contains the HIV viral capsid, a fullerene cone made of individual protein subunits.

The HIV capsid has been the subject of much research in recent years. Attempts to construct the HIV capsid in vitro have not been successful under physiological conditions. Addition of salt to a high concentration results in the formation of tube-like arrays or extended lattice structures.2 Underlying this difficulty is our failure to fully understand the fundamental principle of self-assembly. In particular, due to the difficulty of controlling protein interactions given their complexity, and the nano-meter scale on which the proteins self-assembly, the problem of capsid formation is of particular interest. Additionally, a greater understanding of the HIV capsid may help develop avenues for therapeutics.

The Problem

Self-assembly is a fundamental principle governing the coordination of component parts to synthesise biological systems. Individual subunits are only able to interact with their immediate neighbours, and yet form complex systems capable of performing emergent functions. We observe self-assembly in nature at every scale including with biomolecules. And yet, for a principle so entwined with the very existence of life, we know very little about it.

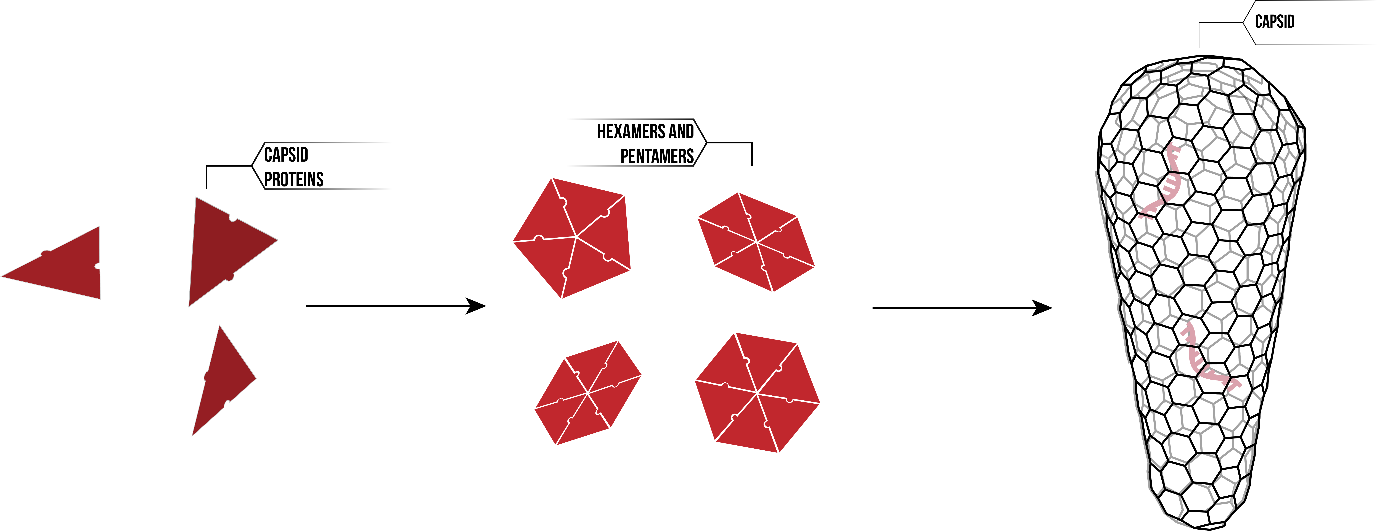

The HIV capsid is one such self-assembling system. The capsid acts as a protein shield, surrounding the viral RNA within. Whilst the three-dimensional fullerene cone looks complicated in structure, it is in fact made up of a single protein; HIV-1 capsid proteins. Thousands of CA proteins interact on the molecular level, first forming hexamer and pentamers, and then assembling into the HIV capsid.

Individual protein units must contain encoded information leading to the self-assembly of the capsid structure. This information may relate to the interaction between proteins, conformational changes that occur during the self-assembly system, reaction to changes in environmental conditions. However, given that our proteins are a mere 26.6kDa, conventional measuring technologies are insufficient. Instead, we needed to develop innovative and novel methods to discover more about the principles of self-assembly.

In order to gain any further understanding of the process of organisation at a biomolecular scale, we have chosen to characterise the construction of the HIV capsid. However, whilst accessing and expressing wild type CA proteins was within reach, observing their interaction and mechanism of assembly served to be a far more difficult task.

Ultimately, our project came down to a single question; how do we accurately characterise not just the final product of an assembly process, but also the steps necessary to produce that final construct? To that end, we have developed a method that may be applied to investigation of other self-assembling systems.

Merit

Our Solution

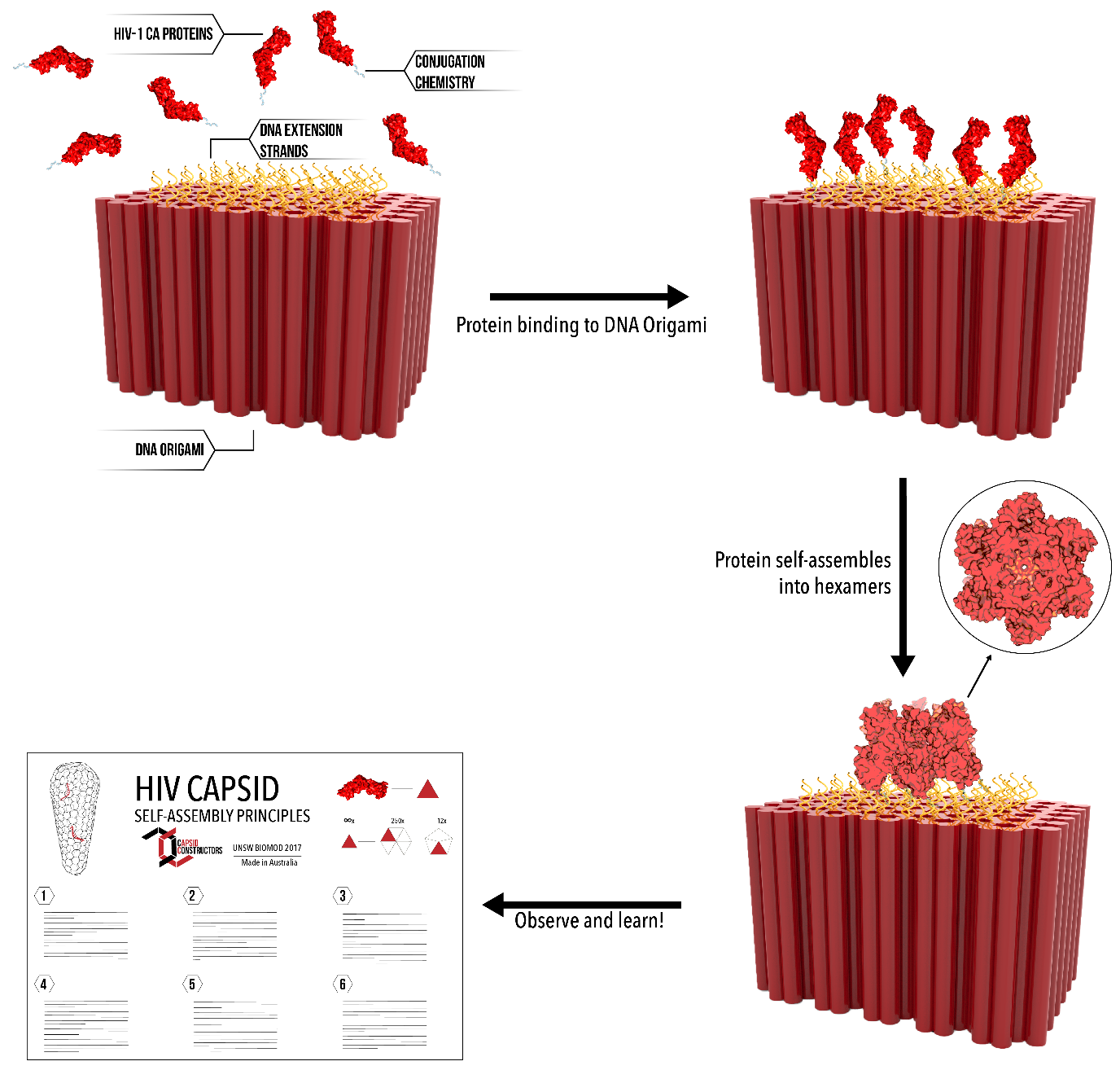

Our solution is to construct the HIV viral capsid artificially using synthetic DNA structures to template the self-assembly of capsid proteins. We can construct arbitrary shapes with DNA origami, and attach proteins at fixed distances with sub-nanometer precision. This allows us to control, manipulate and observe the process of self-assembly on a molecular scale.

We were successfully able to develop a methodology that allowed us to conjugate engineered proteins to carefully designed DNA structures. By building the HIV capsid from the ground up, and with control over the variables within each self-assembly experiment, we were able to move towards a comprehensive understanding of this complex assembly phenomenon.

Our overall solution, that being of artificially reconstructing the HIV capsid outside of the cell, required answers to many smaller questions ranging from protein mutation to kinetic measurements. By considering various idealised experimental designs which would allow us to test particular self-assembly principles, we produced materials capable of answering our various hypothesise and draw conclusions about self-assembly generally. We also provide the opportunity for others investigating their own self-assembly system to implement our methods.

Specification & Feasibility

Goals

When deciding upon our BIOMOD project, we tried to strike a balance between goals that were achievable, given the short time frame of the competition, but still intriguing to each of us as scientists, and relevant to current areas of biomolecular design investigation. Characterisation of the HIV viral capsid system of self-assembly is a deeply significant aim, but for the purposes of the BIOMOD competition, we have focused on developing a robust protocol of achieving this purpose, and developing upon this as much as was experimentally feasible.

In order to isolate and observe fundamental structural and kinetic principles driving self-assembly of the HIV viral capsid, we aimed to produce a modular DNA origami scaffold. This was designed to bind and localise HIV-1 CA proteins using tunable conjugation chemistries, creating an environment in which protein binding events could be observed and measured to extract fundamental kinetic data. In addition to this, we wanted to characterise our system using a coherent mathematical model, to which we could predict and analyse our experimental data. We hope that this model may be applied to other systems as well.

To help in understanding how each aspect of our project fits together to achieve our goals, we have constructed an interactive flow chart. Hover over the hexagons to see more!

Ideal goal for this project

The final goal of our project is to artificially construct the HIV viral capsid in vitro, using a DNA origami scaffold. In doing so, we hope to derive fundamental kinetic and structural principles which govern the process of self-assembly. By characterising this system, we aim to develop a protocol by which may other mechanisms of self-assembly can be understood.

Our more realistic goals for this project

Unfortunately, the time restraints of the BIOMOD competition mean that it is not feasible to completely decipher a fundamental process driving the formation of all life. We would need a couple more weeks for that. In order to make our project achievable within the time frame, we have broken our project down into core goals which demonstrate key aspects of self-assembly of the HIV viral capsid.

- Protein Engineering - Can we make HIV capsid proteins capable of being attached to DNA origami structures?

- DNA Design - Can we construct a synthetic template for the capsid lattice?

- Conjugation Chemistry - Can we successfully conjugate proteins to DNA origami both reversibly and irreversibly?

- Kinetics - Can we obtain quantitative data of protein-protein and protein-DNA interactions?

- Modelling - Can we model steps in the capsid protein cone formation and derive protein-protein binding affinity

- Imaging - Can we confirm our DNA origami structures and confirm attachment of capsid protein to them?

- Small Angle X-Ray Scattering (SAXS) - Can we characterise the solution structure of our protein constructs?

Future Directions

We believe that the methodology we have developed for investigating self-assembly is an interesting and novel approach, in which a large amount of future research could be conducted. We see a number of potential avenues that stem from our work, including:

Single molecule analysis of seeded lattice formation

The ultimate aim of investigating isolated protein binding events is to characterise the entire system of assembly under physiological conditions. By conducting a single molecule analysis of how a lattice of HIV-1 CA proteins form, our primary assumptions may be tested and verified. This is a step closer to understanding how the formation of the characteristic fullerene cone is coordinated in vivo, without formation of tube-like arrays or extended lattices.

Testing HIV-1 targeted drug delivery systems

If we understand how a system works, then we can better understand what steps are essential to its successful proliferation. These steps can be identified as areas to disrupt, using targeted drug technology. Our methodology may provide a useful platform for such developments, enabling other researchers to test whether specifically designed substances can inhibit protein interactions, and therefore survival of the HIV virus, under physiological conditions.

References

- Baker M et al. Domain-swap polymerization drives the self-assembly of the bacterial flagellar motor.Nat Struc Mol Biol 23(3) 197-205.

- Pornillos O. et al. X-Ray Structures of the Hexameric Building Block of the HIV Capsid.Cell 137(7), 1282-92 (2009).

- Pornillos et al. Atomic-level modelling of the HIV capsid.Nature 469 424-427.

- Blair W et al. HIV Capsid is a Tractable Target for Small Molecule Therapeutic Intervention.PLoS Pathog (2010) 6 (12).

- Ehrlich LS, Agresta B E & Carter C A. Assembly of recombinant human immunodeficiency virus type 1 capsid protein in vitro. J Virol (1992) 66(8) 4874-83.

- Rothemund, P. Folding DNA to create nanoscale shapes and patterns. Nature 2006 440 297-302.